Virgil’s Aeneid: The Importance of Initiation through Quests

Like The Iliad and The Odyssey, Virgil’s Aeneid is a classic in the epic-poem repertoire. Even today, the narrative still inspires fantasy writers, who have no qualms about revisiting it, or even layering new meaning onto its tales.

A Classic Epic Poem

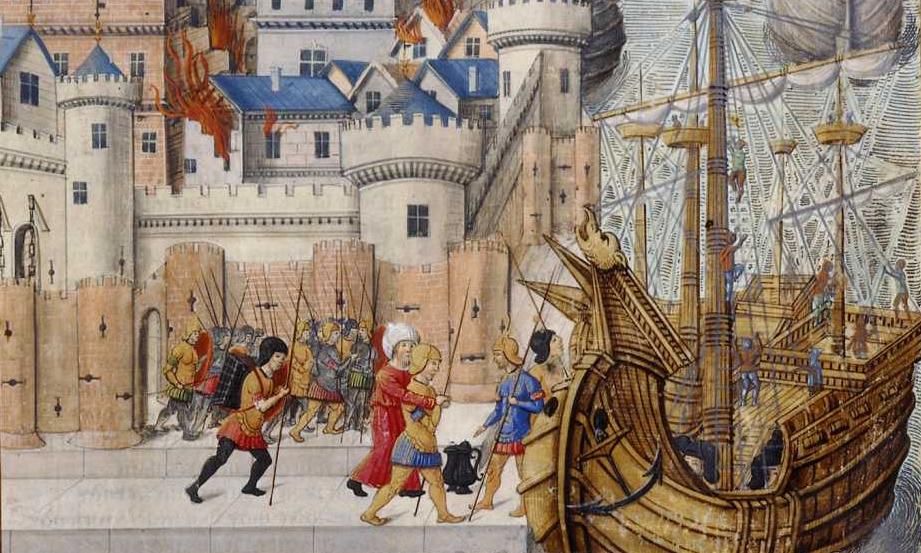

Virgil’s Aeneid (towards 29-17 B.C.E.) develops the legend of the city of Rome’s Trojan roots. The poem opens with a small group escaping from the massacre that followed the Fall of Troy. Led by the hero Aeneas, who also brought his father; his son, Ascanius; and the protective household gods of Troy, the Aenads, as they are collectively known, the survivors begin a long journey around the Mediterranean in search of a new home. After a stay in Carthage, where Aeneas has a tragic love affair with the queen, Dido, they eventually reach Italy, and, after long battles with the locals, manage to settle in Latium, a region in central Italy. The poem closes with Aeneas’s victory, which will allow him to marry the daughter of King Latinus and to found the city of Lavinium. His son Ascanius will in turn found the city of Alba Longa, whence, four centuries later, Rhea Silvia, a priestess of Vesta will be banished before giving birth to the twins Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome (753 B.C.E.).

Virgil’s poem is divided into two equal parts of six books each. It retells the Homeric epic in chiasmus, condensing into a single poem. The first part of the Aeneid follows the plot of the Odyssey (eighth century B.C.E.). Virgil relates the hardships endured by the Trojans, who are roaming around the Mediterranean at the same time as Ulysses. The second part is a new Iliad (eighth century B.C.E.), bursting with epic battles between the Trojans and the Latins, who are led by the the hero Turnus and his ally, Camilla, queen of the Volsci. It ends with Aeneas’s victorious duel with Turnus. Like the Homeric epic it is based on, Virgil’s poem leaves plenty of room for the supernatural, including interventions from the deities: Venus assisting her son, Aeneas, while Juno’s anger pursues him relentlessly, and Aeneas descending into the Underworld to consult with the soul of his father, Anchises.

Virgil’s epic poem was an instant “classic,” studied at school from the first century onwards. Since Antiquity, countless other literary and artistic works have been based on The Aeneid. Certain episodes, like the tragedy of Dido, and Aeneas’s journey to the Underworld, have entered the canon. This epic tale of a defeated people featuring an exiled prince seeking to found a new kingdom has been a veritable wellspring of inspiration for works of fantasy.

The Aeneid in Tolkien’s Oeuvre

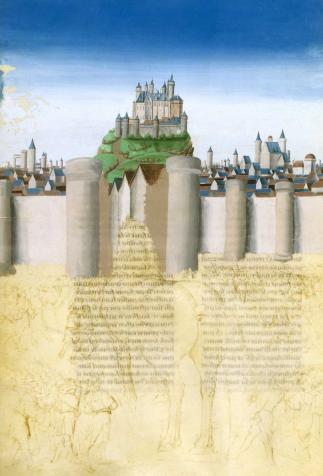

Tolkien borrowed greatly from medieval and epic military poems, particularly The Aeneid, for The Lord of the Rings (1954-1955). He provided the English with a “founding narrative,” one that recounts the mythical foundation of a “secondary world,” as he put it. Tolkien’s saga includes plot lines from the Virgilian epic: the siege of Minas Tirith, reminiscent of the one of Troy; Aragorn, an exiled prince, like Aeneas, follows the Path of the Dead, reprising the Trojan hero’s journey to the Underworld. Gandalf and Frodo also have experiences of katabasis, in the mines of Moria and the devastated lands of Mordor. And, like The Aeneid, The Lord of the Rings ends with the exiled prince’s victory, the re-founding of a kingdom, and a coming wedding.

Letting The Aeneid’s “Second Voice” Be Heard

More recently, David Gemmell turned Aeneas into one of the heroes of his trilogy Troy (2005-2007). It revisits the events of the Homeric epics and The Aeneid, from the roots of the Trojan War to when the the surviving Trojans found a colony in a place called the Seven Hills. But other fantasy writers choose to go head-to-head with what was long the standard interpretation of The Aeneid, as the narrative of the founding of an empire, proposing versions that offer a different perspective.

That is particularly the case for counter-narratives that adopt the point of view of one of the secondary characters in the Virgilian epic. Thomas Burnett Swann’s Green Phoenix (1972) and Queens Walk in the Dusk (1977) present the events of The Aeneid through the usually marginal gaze of Aeneas’s young son, Ascanius; while Ursula K. Le Guin’s Lavinia (2008), rewrites The Aeneid in the voice of Aeneas’s wife, who remains outside the limelight of the Virgilian epic. These fantasy novels shift warriors’ heroism and the birth of Rome to the sidelines in order to focus on what critics have termed The Aeneid’s “second voice,” allowing us to hear the lamentation of suffering individuals at the heart of the boastful celebration of an empire’s future glory.