Video Games: More and More Immersive

Right from the start, the video-game industry developed a powerful bond with fantasy by constantly striving to allow players to penetrate further into imaginary worlds, and by using networking to enable them to experience multi-player adventures from the hero’s point of view.

Video gaming is the world’s largest cultural industry, uniting huge numbers of fans of all ages. As the heir to evolutions in literary fantasy and tabletop role-playing games, it has become the favored medium for expressing fantasy’s creativity.

Fantasy in Video Games

Video-game “genres” are not the same as the ones for books or movies. They are more likely to be defined by the type of action they entail: shooter, platform, simulation, strategy, sports, action-adventure, puzzles and more. The atmosphere is considered part of the background or setting, rather than part of the gameplay (the way the player interacts with the game) itself. Therefore, that background level is where categories like fantasy, thriller or horror come into effect, overlapping with the previous ones.

Some episodes of The Legend of Zelda (Nintendo), for example, are considered a platform game; but overall it is considered an action-adventure game with a fantasy theme. The franchise’s first entry, in 1986, gained acclaim for pioneering a “save” function that allowed players to stop play and resume from the same point later, as well as for its “top-down perspective,” or bird’s-eye-view camera angle. To date, the franchise has had 19 main entries (up to Breath of the Wild, in 2017), creating a timeline of the quest performed by various incarnations of Link, the recurrent hero. How will the young elf manage to get to the end of each level, find the pieces of the Triforce, and rescue Princess Zelda and/or the world of Hyrule from the clutches of evil Ganon once again?

Rapidly evolving technology (including data storage capacity, graphic boards that make it possible to generate the high-quality 3-D images we are now familiar with, and new kinds of on-line networking and hosting) have considerably improved games’ speed, fluidity, immersiveness, and interactivity between on-line players, enabling new kinds of gameplay. So video-game genres tend to evolve quickly.

Yet fantasy still holds its own in video games, because it offers a set of “ready-made” references that are sufficiently familiar to everyone to be activated automatically: characters with obvious skills, powers and abilities; and, most importantly, a world filled with adventures and magic. Video games have in fact established themselves as the most appropriate medium for simulating magical actions in a satisfying manner. They generally have specialized characters (witches, wizards, druids) and dedicated gauges indicating power and energy levels. Those gauges are often (as in Magic, Zelda, Diablo, World of Warcraft, and other game franchises) known as mana bars, “mana” being a borrowing from supernatural legends.

Once Upon a Time in the 1970s

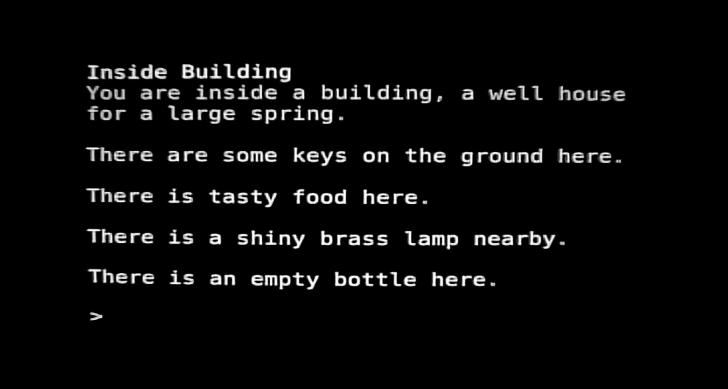

While the earliest arcade games tended to have a science-fiction aesthetic, with space vessels and aliens that were easier to portray with the era’s large pixels, fantasy flourished as soon as RPG (role-playing games) came into existence. It supplied, for example, the setting for the interactive fiction or text-adventure game Colossal Cave Adventure, which was originally designed by Will Crowther, one of the first Arpanet (the ancestor of the internet) programmers. Don Woods, from Stanford University’s artificial-intelligence lab, developed it under the name Adventure, from 1976.

Interactive fiction computer games, like the famous Zork (from 1979) were the prototypes of network games, known as MUD (Multi Users Dungeons). With the addition of graphics, they eventually evolved into MMORPG (Massive Multiplayer Online RPG), like World of Warcraft. They all provide the collective interaction (albeit remotely, from behind a screen) of table-top RPG that was lost in earlier, single-player video games, but which seems to be consubstantial with fantasy. Bard’s Tale, from 1985, popularized dungeon crawling – a type of gameplay that involves exploring a maze-like closed space – with a schema known as “open the door, hit the monster, grab the treasure,” or just “door-monster-treasure.”

Thanks to Warren Robinett, in 1979, Adventure, which modelled movement along cinematic conventions, became the first graphic adventure game. It was followed by King’s Quest, by Roberta Williams, who founded the company Sierra On-Line in 1984, introducing her trademark humor to video games. The graphics, which were improving as the number of colors increased, still tended to be rudimentary back then. But one game really stood out on that score: Dragon’s Lair. Appearing in American arcades in 1983, thanks to the participation of Don Bluth a master of animated film, it was a full-fledged animated cartoon, with interactivity, too. In a totally different style, enigmatic and contemplative, 1993’s Myst helped make exploring worlds one of video games’ main activities.

Many successful fantasy RPG, like Wizardry, Ultima and Might and Magic, have turned into long-lasting franchises. Ironically, probably the most famous game franchise with the word “fantasy,” in the title, Final Fantasy, tends not to adhere to the usual conventions of the genre. Instead, in essentially discrete episodes, it provides syncretic, varied environments that borrow quite a bit from science fiction.

The Mana series hewed much more closely to the fantasy world. RPGs were still a key genre for fantasy games, with Neverwinter Nights and Baldur’s Gate, which based their lush environments and stories on Forgotten Realms (the Dungeons & Dragons setting and series of novels), and fabulous “open-world” series, like Dragon Age and The Elder Scrolls.

Taking advantage of significant advancements in digital imagery, many games really stood out for their grandiose aesthetics, which drew on various fantasy sub-genres. One stunning example would be Dark Souls (2011, Bandaï Namco), with its particularly dark and mysterious universe.

The Warcraft series (since 1994, with Orcs and Humans) established itself as iconic in the “real-time strategy” (RTS) genre, in which you have to manage an environment’s resources as well as using it as a battleground, in top-down perspective. RTS games have become key to our game habits thanks to the development of casual gaming, with little mobile or Facebook games that are designed for the general public, and don’t require any significant investment or skills.

Persistent Worlds

The digital environment has also allowed for the appearance of new kinds of magical worlds. MMORPG’s extremely immersive “persistent words” revolutionized video gaming in the 2000s. They introduced both new development studios and new playing habits (because of the importance of social relations within communities) as well as innovative economic models (monthly fees and purchasing virtual products). Somewhat like Dungeons & Dragons for table-top RPGs, but on a whole other scale, one game, World of Warcraft (WoW, Blizzard Entertainment), has largely dominated the field, which is almost synonymous with the medieval-fantasy universe, with games like EverQuest (Sony Online Entertainment), Dark Age of Camelot (Mythic Entertainment), Ultima Online, Lord of the Rings Online (LOTRO), and The Elder Scrolls Online (Bethesda Studio).

What makes MMORPG so powerful is the appeal of entering a shared, persistent world – the game isn’t just at users’ beck and call, activated only when they turn on their PC or their console – it is an inhabited, perpetually changing world that player-subscribers, generally grouped into “guilds,” can import their avatars into while they are connected. When players disconnect, the game’s world continues to evolve, and their rivals can make progress; this accentuates the impression of a parallel reality, as well as increasing the temptation to keep playing! So Azeroth, in WoW simulates a world with its own unique fauna, flora, cultures, professions, places and more. That world is constantly growing and evolving, thanks to successive “expansion packs.”

Battles beat out exploring once again in MOBA (Multiplayer Online Battle Arenas). Those multi-player games’ predecessor, Defense of the Ancients, was a spin-off from Warcraft III and its emblematic title League of Legends (Riot Games, since 2009). The games, in which two teams of Champions with diverse features fight to conquer enemy terrain, have led to the largest e-sport competitions in the world, particularly in South Korea and China.

When Magic Enters Our World…

And finally, augmented-reality games, like Pokémon Go and Wizards Unite, spin-off from famous environments (e.g. Pokémon and Harry Potter) inserting their magical features into our daily lives by organizing geo-localized treasure hunts, and making it feel like magic is truly within arm’s reach.