Fantasy Crosses the Atlantic

Having first emerged in the United States in pulp magazines, fantasy soon conquered a devoted readership that felt proprietary towards the genre, invigorating it and offering it global reach.

Born in England, fantasy was cultivated there by great artists and respectable scholars as a legitimate, even noble, form of literary and artistic expression. Yet contemporary fantasy, which is based on action, escapism, suspense and identification, is a popular, mass-media genre. This specificity arose essentially in the United States, a country with a tradition of pulp fiction. Fantasy emerged there in the 1930s – at the same time as it was being developed in England. That was the context that enabled the genre to truly take off in the late 1960s and 1970s.

Pulps’ Key Role

In the United States, “pulps” were inexpensive magazines with lurid, eye-catching covers. The term derives from the cheap wood-pulp paper with a dull finish on which the magazines were printed (unlike the “glossies,” which were printed on higher-quality, shinier paper). Having been launched in the late-nineteenth century, they were the main medium of expression for popular literary genres through World War II. Their stories were usually presented in the form of serial adventures with recurring characters. Pulp magazines are the true birthplace of science fiction, with both its name and its classic features being established in them.

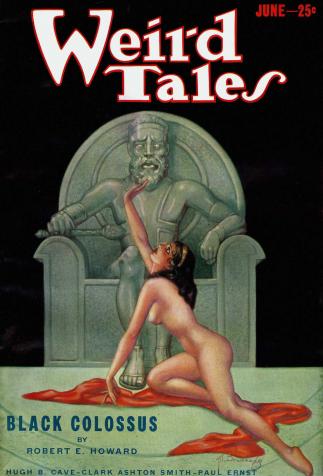

Fantasy, a more porous genre, was still closer to exotic adventures and other speculative genres. The name of the pulp magazine Weird Tales for instance, clearly points more towards the weird or horror fiction that Howard Phillips (H.P.) Lovecraft is associated with to this day. But Weird Tales’ pages were also where Robert E. Howard’s first short stories were published; where Catherine Lucille Moore, one of America’s first female fantasy writers, introduced her heroine Jirel of Joiry; and where her spouse, Henry Kuttner, introduced the character Elak of Atlantis.

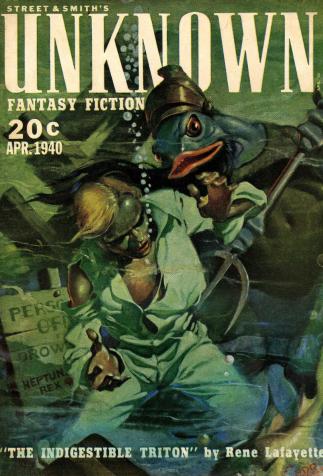

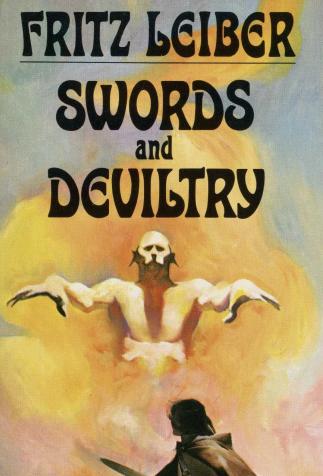

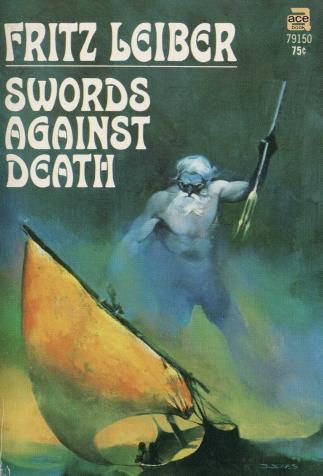

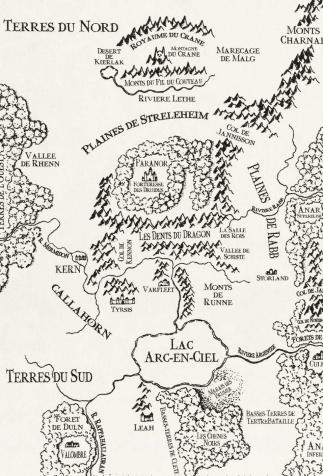

Fritz Leiber’s first novella devoted to the adventures of Fafhrd and the Mouser appeared in the pulp Unknown, in 1939. Leiber would later develop the characters into the protagonists of a vast saga (1970-1988), in which he established some of the genre’s most important conventions: archetypal characters (a duo composed of a sword-wielding northern-barbarian warrior and a mercurial little former-wizard’s-apprentice thief) grappling with capricious gods and evil magic in an urban setting that is also their home base, the dodgy neighborhoods of Lankhmar.

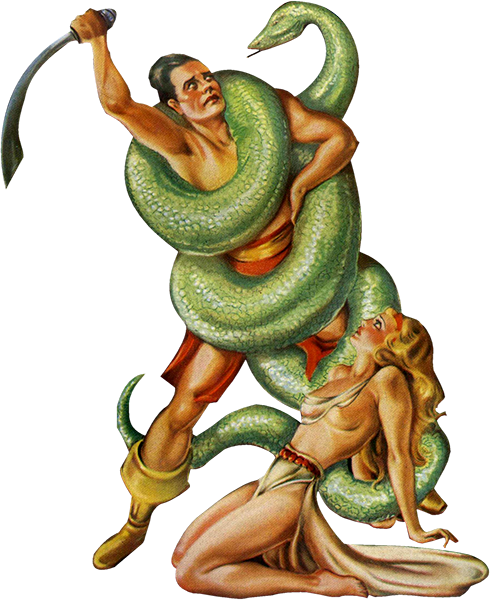

With Conan the Barbarian, who was created by Robert E. Howard in 1932, and the many other pulp heroes and heroines Conan inspired, a specifically American vein of fantasy began to take shape. It is distinctly different from the great British texts from the same era. The American creations are freer in their historical references and morally more ambiguous, as well as being action-packed, paired with appealing visuals and more tightly focused on individual heroic figures. Armed with nothing but their swords and their fierce determination, the American authors’ heroes do battle with generally malevolent supernatural powers, often in dark and violent settings.

That is precisely how the heroic fantasy or sword-and-sorcery sub-genre is often defined. The latter term was coined during a discussion between Fritz Leiber and Michael Moorcock. The English author, whose character Elric of Melniboné, an ill-fated albino emperor whose cursed sword drinks in souls, began to offer his own vision of that model in 1961, in the magazine Science Fantasy.

Hard-Core Fans

Fantasy’s popularity in the United States also comes from the fact that a fervent fan base adopted the genre very quickly, invigorating it and even having a profound influence on its. That base, which is also known as speculative fiction’s “fandom,” is known for its hands-on approach and its significant proximity to the professional world.

The earliest fanzine, The Comet, dates back to 1930; annual conventions started just a few years later. In 1937, Donald A. Wolheim – an editor at Ace Books who went on to found DAW Books, a science-fiction-and-fantasy publishing house – created the “Fantasy Amateur Press Association.” As with heroic fantasy, a second phase of development came in the 1960s-1970s. It turned out to be decisive, because it closely resembles the contemporary situation. A few key figures – second-string authors, as well as publishers and extremely active anthologists – kept the community active.

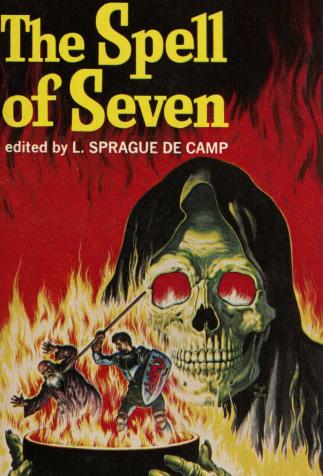

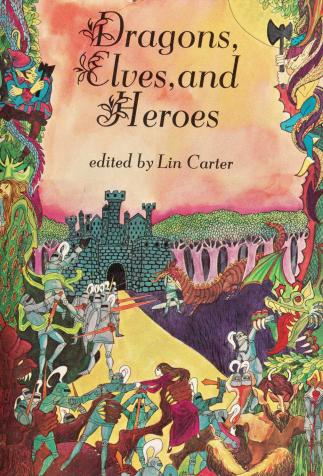

Lyon Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter – who have more recently come under justifiable fire for the way they appropriated the work of dead authors – were also key players. Their opportunism was bolstered by true enthusiasm, and, in addition to the appropriations, they wrote numerous essays, edited collections, and published or republished important texts. Lin Carter did precisely that for many years, from 1969 on, when he was in charge of Ballantine’s Adult Fantasy collection.

The first collective creation, or “shared world,” initiatives began to appear, as did fan fiction, which spins off from published work, developing new material based on an existing character or world. That happened quite a bit with the work of the great female – and often feminist – science-fantasy novelists, like Anne McCaffrey and her Dragonriders of Pern (The Pern Series, 1967-2001), about specially chosen humans who bond telepathically with dragons; and Marion Zimmer Bradley, with her Darkover Series (1962-1999). Bradley, who was very close to her fans, was one of the earliest members of the Society for Creative Anachronism, whose name she in fact coined. Founded in 1966, the living-history group, which organizes “fictional-historic” reenactments, now counts tens of thousands of members around the world.

The 1965 Boom

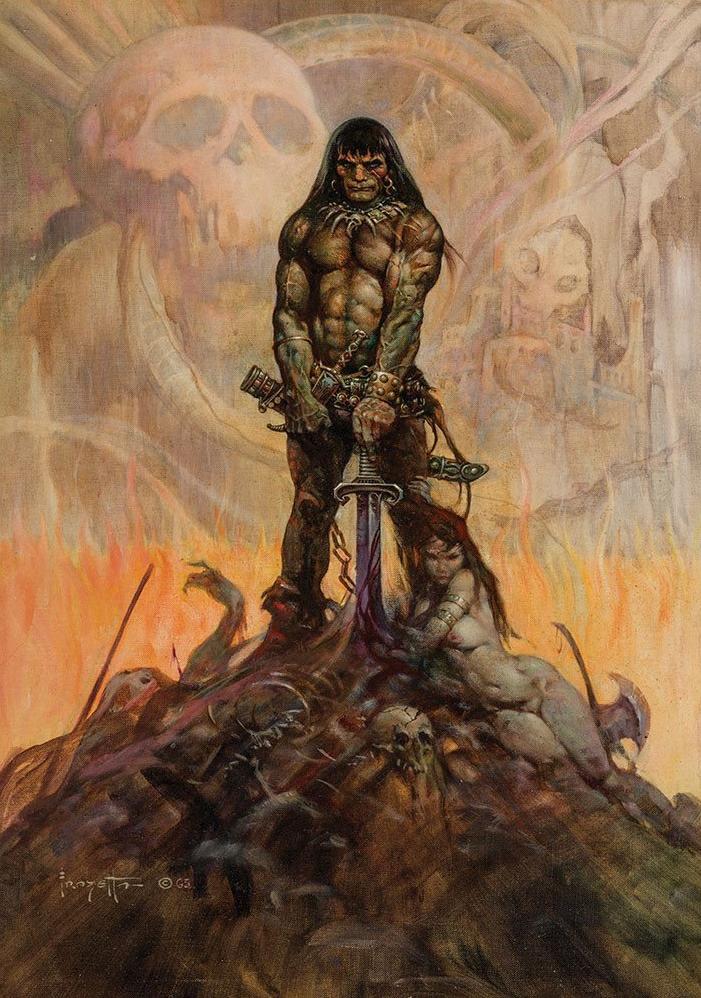

1965-1966 was a banner year for fantasy in America. Two huge paperback best-sellers came out in quick succession: Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, which was published by Ballantine Books; and Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian – in an “expanded” version by Sprague de Camp, who had obtained the rights to the title – was published by Lancer Books. Frank Frazetta’s illustrations contributed to the success of that edition, which has come to be known as the “Lancer Conan series.”

Fantasy’s tremendous diversity was now on full display. The general public had been introduced to Conan, whose “editors” had caricatured him to the extent that the sub-genre he started has been accused of having fascist overtones. That is the point of view taken by Norman Spinrad in The Iron Dream (1972), in which, in a parallel history, Hitler has become an author of fantasy who writes about the adventures of an ubermensch chosen to cleanse the world of corrupt and evil races. In an entirely opposite vein, Tolkien’s noble, epic world was beloved of hippies, ecologists and pacifists. They projected a New Age Eden onto the verdant Shire and its gentle inhabitants who smoked pipe-weed and resisted a bellicose, industrialized Evil empire. During the Summer of Love, “Frodo Lives” and “Gandalf for President” were popular counterculture slogans celebrating imagination.

One can reasonably assume that, in both cases, these were misunderstandings of the authors’ messages, or at best, only partial interpretations that coexist alongside other, entirely different possible meanings. Tolkien, the best-selling author, was paradoxically granted “pop culture” status, to the point that the Beatles were planning to star in a film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings. In 1969, a famous parody, Bored of the Rings (Henry Beard and Douglas Kenney) was even released. But it was thanks to the success of Conan and The Lord of the Rings that Lin Carter was able to launch his collection at Ballantine, and DAW Books to find a place for itself on the popular fantasy market.

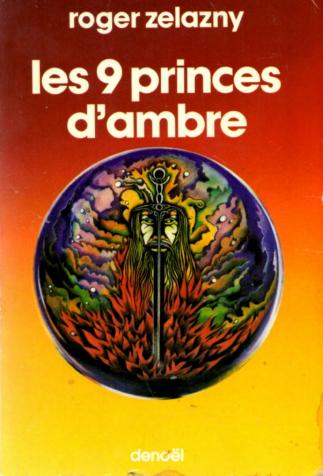

The first role-playing games began to appear around that time, and fantasy illustration also began to come into its own. The genre had carved out a niche for itself in American popular culture, and it would soon go global. Serious writers stepped in: Ursula K. Le Guin, who started her Earthsea Cycle in 1964, and Roger Zelazny, whose first series in the Chronicles of Amber was published from 1970. The series comprises five volumes about Prince Corwin, the narrator. We are first introduced to him as an amnesiac in our world, before traveling with him to the Arthurian “true” world of Amber, where other worlds and realities are no more than Shadows.

One last milestone: the year 1977 was marked, not only by the highly anticipated publication of Tolkien’s Silmarillion, but also by Terry Brooks’ Sword of Shannara, the first series to deliberately distinguish itself from The Lord of the Rings, whose huge popular success had led directly to increased publication of the genre. The characters and overall plot were still lifted from Tolkien, but this time, they were adapted to a post-apocalyptic future that had been blasted back into the Middle Ages and magic.