When the Far North Inspires Fantasy

From frozen lands to strange beasts and mythical gods, many elements that now appear regularly in fantasy actually originated in Scandinavian and Germanic tales and legends that have have come down to us through the ages.

While contemporary fantasy draws on many different sources of inspiration, medieval Scandinavian tales, commonly referred to as “Norse mythology,” show up quite regularly. From divine characteristics inspired by gods like Odin and Thor to monsters like jötunn (frost giants) and trolls, via dragon-slaying heroes with magic weapons, the borrowings are many, and above all, the phenomenon is not a recent one.

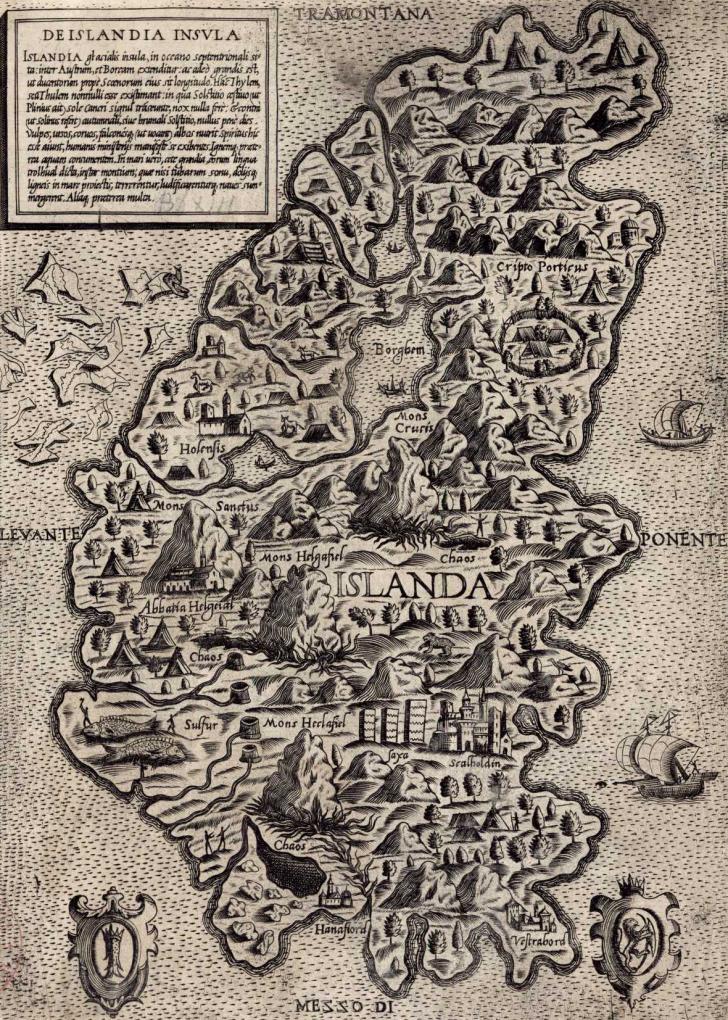

Iceland: Cradle of Norse Mythology

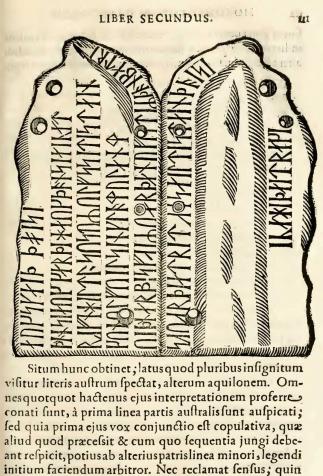

The denomination “Norse mythology” designates a large and diverse body of tales whose written sources generally stem from medieval Icelandic manuscripts transcribed in the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries, i.e. well after the island had been Christianized. These tales are not, therefore, fist-hand accounts from the pre-Christian period. In and of themselves, they already represent rewritings of traditional tales from a bygone era.

The principal sources still available to us are the Eddas and the Sagas, which relate the adventures of Norse deities, heroes and heroines. Some, like Gesta Danorum (“Deeds of the Danes,” Saxo Grammaticus, circa 1200) and Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum (“Deeds of the Bishops of Hamburg,” 1075), were borrowed from texts from continental Europe. The latter work, written by Adam of Bremen, describes a temple with a golden roof in the Swedish town of Uppsala, as well as the sacrifices that were still being performed by inhabitants of the Far North. Hundreds of years later, those features appear in the television series The Vikings (Michael Hirst, since 2013) and the historical fantasy role-playing game Yggdrasil (7e Cercle, 2009).

In addition to the texts, archeological remains from that era can also contribute to fuelling the world of fantasy in different ways.

Norse Mythology Around the World

The history of the reception of Scandinavian culture from the Middle Ages to contemporary works comprises several different stages. Fantasy has powerful ties to the Romantic era, when the Middle Ages came into fashion in reaction to the Enlightenment’s taste for Antiquity. Consequently, medieval works, as well as Celtic and Germanic cultures, were particularly popular. The Brothers Grimm played an important role in reviving awareness of long-forgotten texts in Germany, and in connecting the Germanic and Scandinavian traditions at a time when national romanticism was strong. Their work also had a major impact on the composer Richard Wagner, whose opera The Ring of the Nibelung (1849-1876) draws on the Icelandic Völsunga Saga (thirteenth century), intertwining it with the medieval Germanic epic poem Song of the Nibelungs (thirteenth century). The opera has had a lasting impact on portrayals of Norse gods and peoples, particularly through its costumes, which have contributed to contemporary stereotypes in the popular imagination.

In England, William Morris also displays a taste for Norse subject matter. Over the course of his life, he translated Ancient Greek texts as well as Icelandic sagas, like the Grettis Saga: The Story of Grettir the Strong (1869) and the Völsung Saga: The Story of the Volsungs and Niblungs, with Certain Songs from the Elder Edda (1870), for which he collaborated with an Icelander, Eirikr Magnusson.

Tolkien was in turn impressed by Morris’s work and reworked the Völsunga Saga, giving it a new name, The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún (2009). This rewriting tradition is being carried forward by Neil Gaiman, another English author who revisited Norse legends recently in his Norse Mythology (2017).

How the old Scandinavian tales were received in North America is less well-documented. Nonetheless, authors like Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson refer to medieval Norse texts in their writing. But we are indebted to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow for translating, presenting, and writing both prose and poetry on the subject. His work was well-known to authors like Robert E. Howard, the father of Conan the Barbarian. Rewriting Nordic sagas has been done in the USA as well, as the work of the Danish-American writer Poul Anderson, who rewrote Saga of Hrolf Kraki (1973).

Distinctly Different Contemporary Uses

In addition to the range of different sources and paths by which they came to us, there are also a variety of ways in which references to Norse myths are featured.

On the one hand, the narrative’s plot can be set in the Scandinavian Medieval period, or in an imaginary world inspired by Norse mythology. Examples of this can be found in texts by Poul Anderson, like The Broken Sword (1954), and in children’s and YA books, like Neil Gaiman’s Odd and the Frost Giants (2008). Norse mythological settings are also very common in gaming, including roleplaying games like Asgard (XII Singes, 2011), and Yggdrasil (7e Cercle, 2009), and popular video games, like the latest installment in the God of War saga (Cory Barlog, 2018). A great many fantasy role-playing games, including Runequest (Steve Perrin and Greg Stafford, 1978), Rolemaster (Peter Fenlon, Kurt Fischer and Coleman Charlton, 1980), and Dungeons & Dragons (Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, 1974), offer modules that allow players to incarnate medieval Scandinavian characters in the Viking period.

In addition to the preceding examples, books and games may include Norse elements alongside others inspired by other cultures. The Hyborian Age, the setting for Conan the Barbarian, is a perfect illustration of that type of assembly, in which Norse, ancient Greek and Egyptian, Native American, Oriental and other elements all rub shoulders. The Far North becomes just one component in a vast and heteroclite universe. That type of setting can currently be found in highly successful works, like George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire (from 1996). Although Norse divinities have pride of place in Neil Gaiman’s American Gods (2001), deities from other mythologies do appear. The attribution of myths to certain communities can contribute to creating ties between traditional tales and cultural identities in contemporary representations of media cultures.

A Lavish Bestiary

In a less systematic way, it is also possible to catalogue the presence of many supernatural creatures in fantasy. The bestiaries used in roleplaying games, starting with Dungeons & Dragons, are brimming with examples of this: giants, trolls, dragons, and even swan maidens. Eddic poems were also among Tolkien’s sources of inspiration, both for the names of the various dwarfs in The Hobbit (1937) and for Gandalf the magician’s name. In Robert E. Howard’s work, Hyborian Age northern countries were populated with Aesirs and Vanirs, ethnic groups whose names pay tribute to feuding clans of Gods in Norse mythology, the Ases and the Vanes.

George R. R. Martin employs numerous Scandinavian Medieval references, such as ice giants, images of crows and wolves, the powers of wargs, which allude to those of Odin or the heroes of sagas, as well as the wights, which may be a nod to supernatural Scandinavian living-dead creatures. In narrative terms, the novels’ timeline, which leads ineluctably to the final battle, can also bring to mind the three-year-long winter that is called Fimbulwinter (Fimbulvetr in Old Norse), during which it is said that men will kill each other, and which precedes Ragnarökr (the battle leading to the end of the world, or twilight of the gods).

These various examples make it possible to highlight the idea that references to medieval Scandinavian tales can be found in fantasy at all levels and dimensions, and in all media: landscapes, characters, monsters, plots and events, soundscapes, in the case of audiovisual works, and more.