Role-Playing Games: Making Fantasy Real

Many fantasy readers don’t stop at reading; they often participate actively in the narrative, projecting themselves into the hero’s place, wearing the garb of this or that fictional tribe or society, and spending time with other fans in fantasy’s imaginary worlds.

The term role-playing games (RPG) describes any recreational activity in which participants put themselves in a character’s place, adopting the character’s point of view and abilities, and taking on their motivation and goals for a given period of interaction and adventure.

Table-Top or Live Action

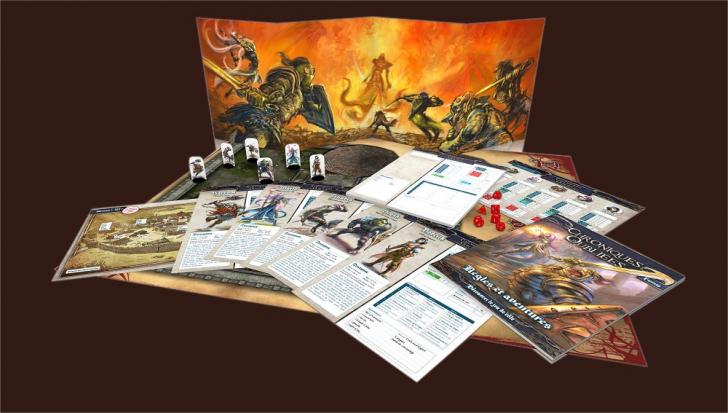

Video and/or on-line games (including textual role-playing games, which are not unlike collective fan-fiction stories) provide different types of recreational appropriations of fantasy worlds, but the all derive from “paper” or “tabletop” RPG. In tabletop RPG, a a group of players gathers around a game master (GM) to narrate and act out a scenario that unfolds in a given world. Players embody characters with specific skills, abilities or powers that determine what they can or can not do. Depending on the task assigned and the obstacles to overcome, players have to make decisions, like choosing what path or action to take, then simulate the consequences. Actions, especially battles, are decided by throwing dice according to complex rules. Long games divided into several episodes that can be played out over months or even years are called “campaigns,” from the military sense of the term.

That’s because although RPG are now strongly associated with fantasy genre, their roots actually lie in wargames, i.e. simulations of historical or alternative battles fought with miniature armies spread out on large tabletop “boards.” In the mid-1960s, some fans who were deeply affected by Tolkien’s founding work, Lord of the Rings, wanted to extend their experience of immersion in a magical world. They made the crucial decision to switch from embodying an entire army to embodying a single character, which made the outcome more personal. At the same time, the context to be recreated shifted towards imaginary worlds that needed to be precisely portrayed in myriad illustrated manuals describing the creatures, cities, weapons and more.

Finally, Live Action Role Playing (LARP) is yet another facet of RPG practice. Born in the 1980s, it didn’t really take off until the 1990s. In this iteration, participants physically incarnate their character over the course of a costumed weekend in an outdoor space reserved for players. Their task might be to prepare for and act out an attack, for example. The largest annual events, like England’s iconic The Gathering, involve thousands of people. But most LARP events take place on a smaller scale.

A Medieval Fantasy Worl

Although there is no shortage of RPGs in other genres and sub-genres (particularly the supernatural, with The Call of Cthulhu and Vampire: The Masquerade), games that take place in medieval-fantasy worlds, which are often quite syncretic, are by far the most popular. The first edition of Dungeons & Dragons (Gary Gygax and Steve Arneson, TSR) came out in 1974, with critical developments occurring in 1977 and 1978, and it remains hugely popular to this day. D&D, whose license was purchased by Wizard of the Coast, the publisher of the famous card game Magic, is now on its fifth edition, which was released in 2014. Dozens of settings, such as “Forgotten Realms,” have been developed over the decades, and there have been many spin-off productions in a range of different media.

The fantasy world Glorantha was created in 1966 by Greg Stafford, founder of the RPG publisher Chaosium. It was the setting for various board games and RPG, including RuneQuest, developed along with Steve Perrin, which was first launched in 1978. Other, more recent games, including Hero Wars and Hero Quest (2000 and 2003, respectively) also take place there. Warhammer, designed by the British authors Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone (who were also pioneers in the “You are the Hero” book genre), started out as a tabletop miniature wargame (Warhammer Fantasy Battle) made by Games Workshop, before being turned into an RPG (Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay) in 1986.

Games inspired by books are also worth mentioning, as they represent a significant portion of the sector. They include Stormbringer (1981) and Elric! (1993), both based on novels by Michael Moorcock, as well as others drawn directly from Tolkien (Middle-earth Role Playing, 1984), and several variations on Conan, since 1985.

Several factors explain this convergence between role-playing games and the fantasy genre:

— The narrative trope of an initiatory quest is easy to duplicate in successive episodes that organize players’ progress.

— The setting is crucial, and fictional worlds, which are open by nature, lend themselves well to exploration and description and can always be enlarged or enhanced.

— Cultural standbys (the Middle Ages, the fantasy or supernatural tradition, and more) offer places, objects, and creatures that are both familiar to players and flexible for game designers needing to “populate” and “stage” imaginary spaces.

— The distribution of skills or “powers” identifying PCs (“player characters” or “playable characters”) and making it possible to sort them into “types” provides the simplicity and legibility needed for good playability. At the same time, taking moral questions into account enables the evolution and sophistication of RPG worlds. Rules will establish both the costs, and the possible benefits of, say, choosing to side with Evil or Chaos.

So medieval fantasy provides a “custom-made” imaginary context that is sufficiently familiar to avoid requiring tediously complicated explanations. That same practical aspect makes medieval fantasy the go-to setting for the vast majority of live-action role-playing events, too. Many factual aspects make them similar to the medieval festivals and “renaissance fairs” that have multiplied internationally since the late 1970s. One must, however, take care to distinguish them from “historical reenactments,” or “living history” events, which take their standards of authenticity extremely seriously. Whereas the shows, and even more so, the participants in costume contests etc., cheerfully weave together elements from actual medieval history (knights and ladies, farmers, etc.) and others from fantasy (elves, orcs, new age witches and more), without feeling obliged to distinguish between the two. Nevertheless, fantasy is being used more and more to draw spectators in to historical sites…

Media Synergy

Although tabletop games and live-action events are enjoyed by a relatively small number of people, their influence on popular culture can not be overestimated. This is true both in terms of practices (action/adventure games, cosplay) and socializing (guilds, communities). Fantasy occupies such a large place in our current cultural landscape largely because of “cosmogonic” media synergies: the idea of “worlds” has established itself as a meeting point at the crossroads between narration and entertaining experimentation.

Role-playing games have had a huge influence on that evolution, as they are central to the highly fertile circulation of ideas and concepts between other fantasy media. “You are the hero” books (especially the ones from the “Fighting Fantasy” series), which offer multiple-choice paths through the text, were also very important to introducing the genre to a younger, broader audience, strengthening their position from the 1980s on.

It is not uncommon for writers to start out creating role-playing scenarios before moving on to novels. In the United States, successive generations of author-creators have followed that path since the late 1970s. Foremost among them, Raymond Feist, whose extremely long Riftwar cycle, begun in 1982, followed numerous campaigns in the world of Midkemia. The connection is particularly noticeable in France, because the fantasy-book and -game publishing developed relatively late, and evolved symbiotically. Out of the top French fantasy novelists writing today, Mathieu Gaborit is probably the one who dovetails the two activities the most, and both Pierre Pevel and Jean-Philippe Jaworski got started as role-playing-game authors.

The ties between the world of RPG and various audio-visual formats for fantasy are equally flagrant. It is obvious when one sector adapts the other’s narratives. But it is also perceptible, albeit more subtly, in a shared ambition that emerges both in LARP and in the making-ofs of Peter Jackson’s films and Game of Thrones. In each case, the idea is to (re)constitute material cultures (weapons, fabric, jewelry and more) as if they had come from other worlds, in a way that empowers fans to fantasize their actual existence.