Inventing Imaginary Worlds

One classic feature of fantasy tales is the profusion of details about the worlds in which they take place. Compelling worlds that entertain and fuel readers’ imagination.

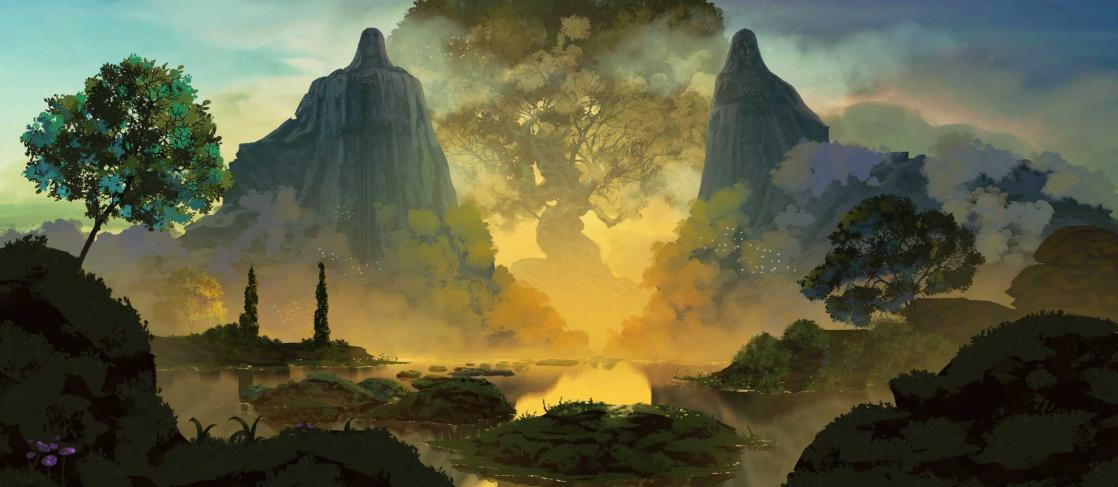

Fantasy can either re-enchant our world by making it magical, or – and this is often what we remember most – propose a whole other, “secondary” world composed with tremendous care and attention to detail. This “world-building” concerns not only the books and their annexes, but also films, which have to provide consistency and plausibility in their portrayals, and of course the physical and digital games in which character-players react to information and input from the world they are roaming through.

Creators of Myths As Well As Worlds

A fictitious world is, by definition, incomplete, because only the parts that have been described are accessible to us. The rest remains indeterminate: we don’t know how many children Lady Macbeth had, or the color of Madame Bovary’s eyes. But in speculative genres, particularly fantasy, the illusion of a full world is taken to an extreme. Despite the marvels they harbor, those worlds feel so real to us, we can picture ourselves strolling through them. C. S. Lewis coined that expression of praise about his friend J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth.

This “cosmogonical” work can be taken to the point of inventing creation myths – like Tolkien’s The Silmarillion and Lewis’s Magician’s Nephew. That turns authors into Creators, or rather “sub-creators,” as Tolkien put it, “commanding Secondary Beliefs,” proposing worlds that, “both designer and spectator can enter,” ("On Fairy Stories”). The desire to achieve that, a distant echo of a childhood practice (C.S. Lewis and his brother had dreamt up a little world called Boxen), profoundly nourishes fantasy creations and fires the imagination of their readers, who are often invited to see themselves as co-creators. In fact, nowadays, fans have no qualms about doing their bit, creating and distributing fan fiction and fan art.

Worlds to Map

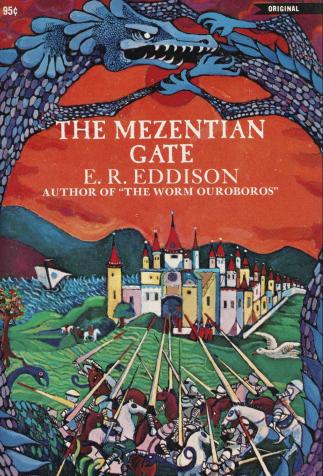

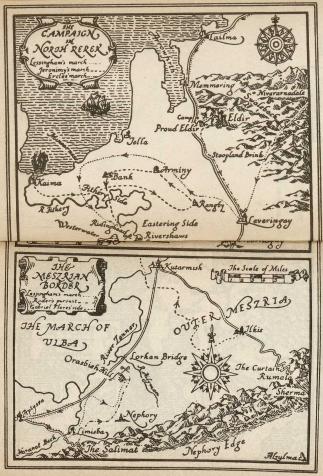

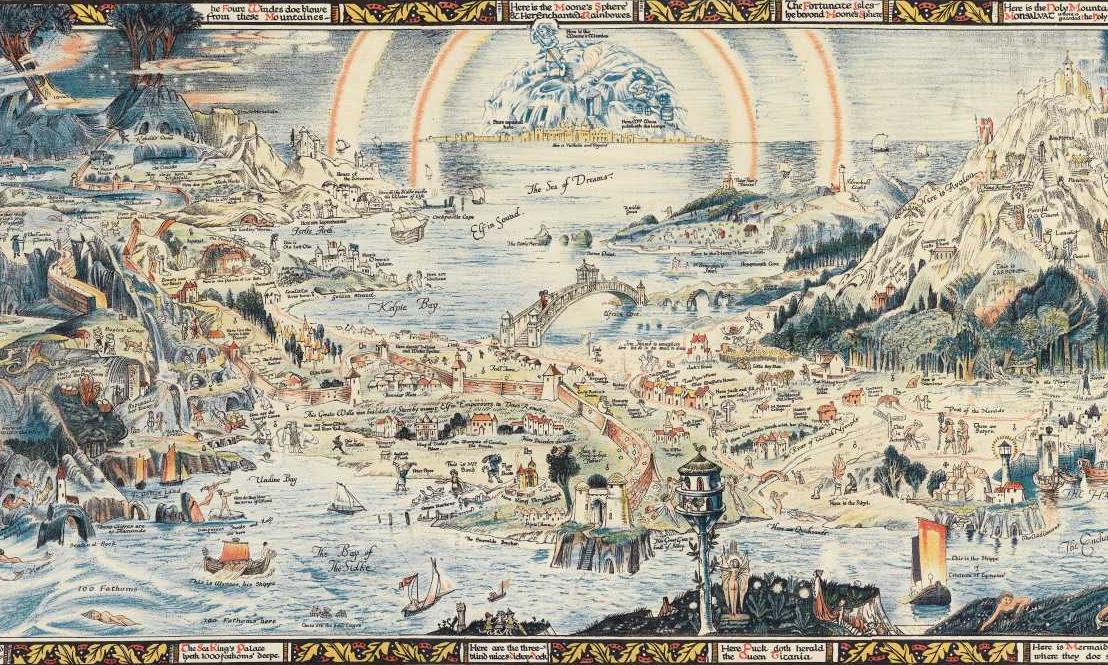

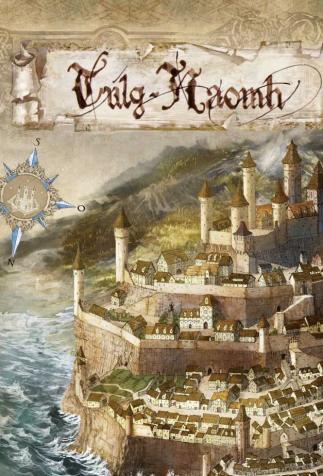

From J.R.R. Tolkien to George R.R. Martin, maps, timelines, imaginary languages, and myths and legends from within the fictitious world have become practically mandatory steps in imaginary world-building. E.R. Eddison, the author of the Zimiamvia novels and one of the pioneers of the between-the-world-wars fantasy revival, did not provide a map in his Worm Ouroboros (1922). But he did include such a wealth of detail in his descriptions of his characters’ paths and the conflicts between Demonland and Witchland that a fan, Gerald Hayes, was able to establish one, before being recruited as the fictitious land’s official cartographer.

The process is more likely to go the other way around, however, with the “form” of the world preceding its contents. R.E. Howard, for example, started creating his Hyborian Age by devising its history, maps, etc. Originally, he had been intending to use it as a setting for various adventures; not just Conan’s, Howard specialist Patrice Louinet explains. For Tolkien, the starting point seems to have been the imaginary languages he had been honing; he wanted to come up with a context where they could be spoken. Fantasy’s plots invite us to roam through worlds that are often introduced with maps – veritable markers of the genre – although some authors, like France’s Jean-Philippe Jaworski, refuse to provide them so as not to rein in readers’ imaginations.

The characters undertake a journey, quest, or apprenticeship that will lead them to the mysterious depths of sprawling cities or the four corners of their world, introducing them to a range of different landscapes and diverse peoples and their lifestyles – including elves, dwarves, trolls and other creatures who have been popularized by the medieval fantasy inspired by Tolkien and role-playing games.

In urban fantasy and steampunk, which favor urban or industrial settings, the plots take the shape of one or more crimes or mysteries to investigate. But they still offer access to secondary worlds we can learn about in a variety of ways, from footnotes in Hervé Jubert’s series of Beauregard investigations (since 2012) to the “monster of the week” format for the TV series Grimm (2011-2017), which featured a new creature in every episode. For that matter, the investigation in question may focus on the Origins of the world itself, or a lost memory that needs to be recovered and transmitted, as in Christelle Dabos’s La Passe-Miroir (“Through the Mirror”) series (since 2013).

Worlds to Document

Whether tabletop or digital, role-playing games have enshrined the principle of a path or quest to follow. Players incarnate characters that move around a map, gradually “unlocking” access to new areas and missions. That structure has become so associated with the fantasy genre that Terry Pratchett could parody it, portraying Discworld through the eyes of a tourist (The Colour of Magic, the first volume in his comic-fantasy book series, 1983), while Diana Wynne Jones wrote a “guidebook” to the genre’s most common tropes, The Tough Guide to Fantasyland: The Essential Guide to Fantasy Travel (1996, revised and updated 2006). The temptation to create encyclopedic reference books about one or more fictitious worlds rather than simply telling stories is another major trend in fantasy.

In Lector in Fabula (1979), Umberto Eco postulated that access to fiction involved the reader’s own “encyclopedia” (all of the knowledge readers can draw on to fill in the text’s blanks). But in speculative genres, the encyclopedia of another world has to be constructed, at least in part, and authors often enjoy flaunting that part of their work. In order to provide in-depth access to a long history, with family trees and alphabets, Tolkien wrote hundreds of pages of annexes to Lord of the Rings, and spent his entire life creating myths for the world of Arda. Some of them were published posthumously in The Silmarillion (1977), before Christopher Tolkien compiled a more complete, 12-volume History of Middle-earth (1983-1996), which made it possible to see the myths’ genetic stratification.

Worlds Stretching to Infinity

In a similar vein, it is not uncommon for fantasy books to include glossaries and/or character lists, and the most developed worlds often have “companion books,” devoted to them. J.K. Rowling, for instance, created the “Hogwart’s Library” collection, allowing her devoted readers to access the same books that Harry studies while at school: first Quidditch Through the Ages and Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2001), then The Tales of Beedle the Bard (2007). That didn’t keep her fans from from creating even larger, more-encyclopedic databases, including Steve Vander Ark’s famous Harry Potter Lexicon. Although Rowling appreciated Vander Ark’s fan site, she sued the publisher over the lexicon in book form, in order to protect her rights to her own creation.

George Martin chose to share credit with the creators of the website Westeros.org for an illustrated book devoted to the history of his world, The World of Ice and Fire (2014), before following their lead and writing his own historical chronicles of his world’s distant past in Fire and Blood (2018).

Artists and game creators have produced lavishly illustrated editions that pay tribute to the work of world-building in art books with evocative titles like The Art of World of Warcraft (since 2005) and How to Art - DOFUS & Wakfu (Ankama, 2008).

The “Ouroboros” collection, published by Mnémos, offers a wide range of “book-world” options. Some are collective (Un an dans les airs (A Year in the Air), 2013, Jadis (Olden Times), 2015) others singular (Hélène Larbaigt’s L’étrange cabaret des fées désenchantées (The Strange Cabaret of Disenchanted Fairies), 2014). Some explore steampunk, an intensely imaginative genre (Mémoires de la France steampunk, 2015, ed. Étienne Barillier and Arthur Morgan); others provide guides to pre-existing worlds in the shape of games and/or books (Abyme, le guide de la cité des ombres (Abyme: The Guide to the City of Shadows) for Mathieu Gaborit’s Abyme, 2009; Tschaï, based on Jack Vance’s, Planet of Adventure, 2017); while still others portray unique worlds in which text and images intertwine (Le Nordique, chroniques retrouvées du dernier convoi (The Nordic Pilgrimage: The Lost Chronicles of the the Last Convoy) by Olivier Enselme-Trichard, 2017, and more).