Ovid’s Metamorphoses: A Universal Reference

Ever since Ovid’s eponymous tale, metamorphosis has been one of the most powerful themes in fantasy. The effect is no less mysterious, or even troubling, for readers, despite its magical cause.

An Unequalled Narrative

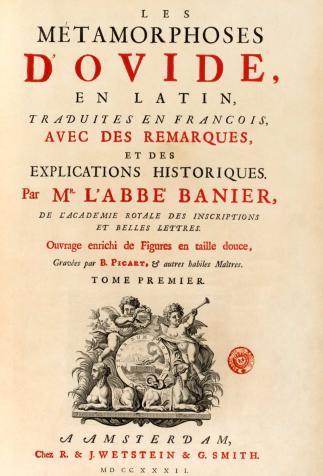

Ovid’s 15-book-long epic poem, Metamorphoses (first century), provide us with a comprehensive and erudite vision of Greek and Roman mythology that has no equivalent, aside, perhaps, from the Greek author Hesiod’s Theogony (eighth century B.C.E.). Ovid’s magnum opus takes the shape of a continuous poem of 12,000 verses, recounting over 230 fables in which the author provides his own version of the full set of myths that had been transmitted orally or in Greek and Roman authors’ work. He offers a history of the origins of the universe, and provides a family tree of the gods, heroes (demi-gods, in etymological terms), and humans, from primitive chaos to Augustus’s founding of the Roman Principate, which marks the passage from mythical to historical times.

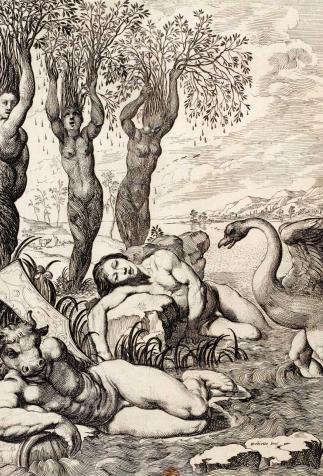

The poem finds its unity in the theme of metamorphosis, which illustrates a philosophy of universal fluidity, an inheritance from the Greek philosopher Heraclitus (fourth-fifth centuries B.C.E.): everything is constantly changing, nothing lasts. Ovid presents a vision of the world in which the only laws are impermanence and transformation; a world where the borders between elements, kingdoms (animal or plant), and species might be erased at any moment. It is usually humans who are turned into animals, plants, or minerals, but the phenomenon does not spare the deities either. The gods cause the metamorphosis to take place, often to punish mortals for their hubris (the weaver Arachne was turned into a spider by Minerva), although sometimes it was to save them from an even worse fate (Daphne was turned into a laurel tree to escape Apollo’s advances), or to offer them a form of immortality (Venus turned the blood of her lover Adonis into a flower) or a reward (Venus brought Pygmalion’s statue to life as a flesh-and-blood woman).

A Storehouse of Myths for Artists

The Metamorphoses has been used for over two thousand years as a vast storehouse of fables that have inspired multiple interpretations, rewritings, and visual, sculptural, and musical representations. The roots of most of the myths that have been reprised in contemporary fantasy can be found in this text, although the stories have often evolved over repeated iterations.

So metamorphosis is a major trope in fantasy, where characters who are susceptible to its effects are legion, like the metamorphmagi Nymphadora Tonks and Edward Lupin, who are able to change their appearance at will in the Harry Potter series (J. K. Rowling, 1997-2007). More commonly, the borders between human and animal blur, as in the case of Beorn, who could assume the form of a bear in The Hobbit (J.R.R. Tolkien, 1937); the animagus Sirius Black, who metamorphoses into a dog in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (1999); Shaé – a panther and an eagle in L’Autre (“The Other,” Pierre Bottero, 2006-2007), or some druids who can turn into forest creatures in the role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons (Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, since 1974).

The myth of Lycaon, the cruel King of Arcadia who was turned into a wolf by Jupiter in Book 1 of The Metamorphoses, has also had a fabulous number of descendants in fantasy. Lycanthropy features in both Harry Potter and Twilight (Stephenie Meyer, 2005-2008), as well as in the TV series True Blood (Alan Ball, 2008-2014) and Teen Wolf (Jeff Davis, 2001-2017). Fantasy offers numerous examples of cohabitation or fusion between human and animal souls: Lyra Belacqua and her dæmon Pantalaimon in His Dark Materials (Philip Pullman, 1995-2000), Fitz and the wolf Nighteyes he wit-bonds to in Robin Hood’s Royal Assassin (1995-2017), Bran Stark and the crow (changed to a raven in the TV series) that transmits its gift of green-sight to him in George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones (since 1996). But metamorphosis can also turn out to be retribution, like Eustace’s punitive transformation into a dragon in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (C.S. Lewis, 1952).

Timeless Creatures

The borders between human and plant can also be blurred at times, as in Alain Damasio’s La horde du contrevent (“The Horde of Counterwind,” 2004), in which the character Steppe turns into a birch tree. The White Witch of Narnia turns her enemies to stone in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (C.S. Lewis, 1950), while the greyscale that afflicted Jorah Mormont in Game of Thrones is also a kind of petrification.

Lastly, a great many creatures inherited from Greek and Roman mythology as it was passed down to us by Ovid now populate fantasy’s various worlds. The Dryads and fauns found in Narnia and in the Centaur colony in Hogwarts’ Forbidden Forest, as well as myriad winged horses, sirens and three-headed dogs, were crafted from imaginative material that has been disassociated from its original world and become timeless.