Fantasy Comes to Life on the Big Screen

Thanks to technological advancements, fantasy settings and characters in movies are constantly evolving and becoming more and more inventive, even going so far as to bringing them into three-dimensional existence.

The bond between illusion and the fantastic goes back to the origins of filmmaking, with George Méliès, magician and master of special effects. But fantasy films are constantly seeking new technology in order to offer spectators a compelling visual experience.

Animated Films

Animation, whether traditional hand-drawn or computer-generated (CGI), lends itself perfectly to portraying magical worlds, because it enjoys a complete freedom that is denied to live-action filmmaking. In addition, most animated films are intended for young viewers, who are keen on the fantastic. Disney Studios, which has been decisive in forging young viewers’ cultural representations since the 1950s, has made adaptations of both traditional fairy tales and founding books of fantasy for children, including Alice in Wonderland (1951), Peter Pan (1953), Mary Poppins – which combines live-action and animation (1964) – and, with medieval overtones, The Sword in the Stone (1963, based on the book by T.H. White) and The Black Cauldron (1985), based on Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain Chronicles.

Aesthetic experimentation began in the 1970’s, but things didn’t always go as planned. Ralph Bakshi, the director of Wizards (1977), had to give up on his adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, and his rotoscope technique, after a single episode in 1978. With a top-notch artistic team led by Brian and Wendy Froud, Jim Henson’s The Dark Crystal, a puppet film (in fact, Henson’s first film that didn’t feature the Muppets), has acquired cult status over time, despite having been something of a flop when it was released, in 1982.

While the Shrek parody series, which falls under fairy-tale fantasy (Dreamworks, since 2001), was one of the biggest CGI hits of the turn of the century, traditional animation techniques continue to be made for their uniquely poetic feel. One example is Henry Selick’s stop-motion animation in the dark fantasy films The Nightmare Before Christmas (conceived and produced by Tim Burton, 1993) and Coraline, adapted from the Neil Gaiman book (2009). France has also had some noteworthy hits, like Michel Ocelot’s famous Kirikou films (since 1998) – magically mischievous animated African tales, as well as his Princes and Princesses (2000) and Tales of the Night (2011), which use silhouette in a shadow-puppet style.

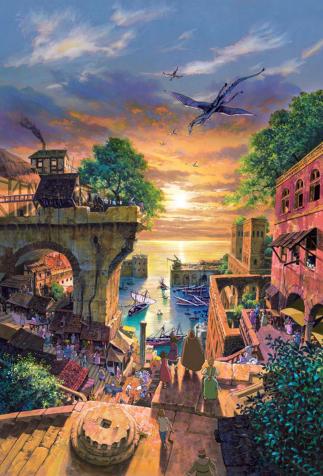

Of course, the marvelous world of Japanese animation is dominated by Hayao Miyazaki’s creations at Ghibli Studios. Some are inspired by myths and legends (Princess Mononoké, 1997, Spirited Away, 2001, Ponyo, 2008), while Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) is based on the book by the same name by Diana Wynne-Jones. Miyazaki’s colleague Isao Takahata explored the lives of kami and yôkai spirits of Shinto legend; while his son, Gorō Miyazaki, proposed an adaptation of Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea cycle, Tales from Earthsea (2006).

Films for Young Audiences

Many live-action fantasy films are also aimed at young viewers. The films are often adapted from children’s fantasy books, like Terry Gilliam’s Time Bandits (1981), Wolfgang Petersen’s NeverEnding Story (1984, based on Michael Ende’s book, 1984), and Willow (Ron Howard, 1988), a family film about dwarves who take in a human baby. Rob Reiner’s sidesplitting parody film, The Princess Bride (1987, based on the novel by William Goldman) is not far off the mark!

The hugely successful adaptations of the Harry Potter series (since 2001) shed light on the new media synergies at work in children’s literature. But out of all the films that jumped on the bandwagon, few actually caught on with moviegoers. The adaptation of C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia (Disney, 2005-2010), was stopped after three episodes due to disappointing box-office returns, as was the Arthur and the Invisibles series of animated/live-action films based on director Luc Besson’s own books. Only the first of those films, from 2006, had any significant success. Other movies under-performed to the point of being out-and-out flops, despite having significant budgets and/or being based on hugely popular books. Those debacles include Eragon, based on the book by Christopher Paolini (directed by Stefen Fangmeier, 2006); Inkheart, from the best-selling novel by the German author Cornelia Funke (directed by Iain Softley, 2008); The Golden Compass, based on Philip Pullman’s Northern Lights, a film described as a huge “industrial accident” for New Line productions (Chris Weitz, 2007); and M. Night Shyamalan’s The Last Airbender, inspired by the televised animation series Avatar (2010).

Ever-Evolving Techniques

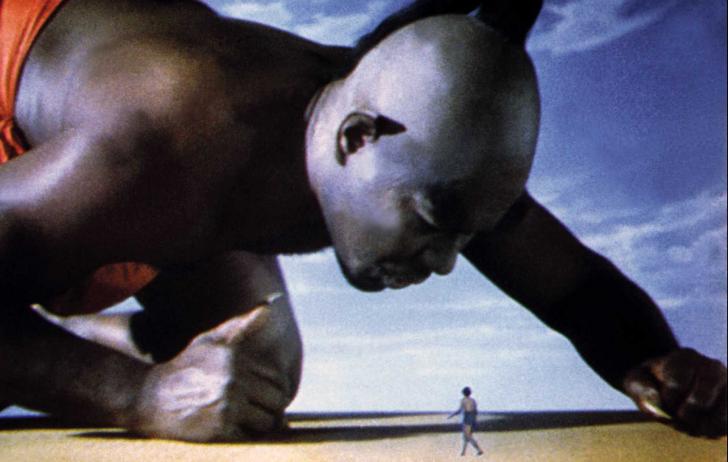

The cinema has offered visual interpretations of all of fantasy’s sub-genres, and, thanks to the popularity of the medium, has often introduced them to a broader audience. Enchanted Arabian tales inspired by the 1,001 Nights provided lasting inspiration to filmmakers, in the 1920s (Raoul Walsh’s Thief of Bagdad, with silent-film star Douglas Fairbanks), and even into the 1940s and ‘50s, despite the fact that it had fallen from grace in literature. The genre also benefitted from the stop-action animation technique for snippets incorporated into live-action film. The technique worked well for scenes with monsters, which Ray Harryhausen excelled at, as in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and numerous peplums (a film genre that is close to fantasy). Growing ever more kitschy, the vein lasted into the 1970s.

The following decade saw the multiplication of sword and sorcery movies. The first, blockbuster Conan (John Milius, 1982) came after John Boorman’s Excalibur (1981), a boldly colored version of the Arthurian legend inspired directly from Malory. Although the Conan film was a far cry from Howard’s books, it sparkled with memorable scenes and lines that have made it a cult classic. Despite their respective qualities, Ladyhawke, a medieval tale of enchanted lovers (Richard Donner, 1984); Ridley Scott’s Legend (1985); and Rob Cohen’s DragonHeart (1996), from the early era of digital effects, prove that fantasy’s magic rarely ages well on screen. Straying towards the edges of the genre, the original Star Wars trilogy (1977-1983) is still enchanting, but George Lucas insisted on “remastering” his films with more recent digital techniques that had become available.

The Special Effects Watershed

Peter Jackson, on the other hand, waited until everything he needed to bring his vision of the book to life – including motion capture and green screen technology – was available before launching into his adaptation of Tolkien’s inexhaustible Lord of the Rings (2001-2003). Along with the Harry Potter films, Jackson’s box-office-record-breaking and Oscar-winning films’ phenomenal success has had a long-term impact on fantasy films. That success was also due in part to New Zealand’s stunning natural landscapes. In that sense, fantasy has inherited westerns’ appeal by offering a visual celebration of wide-open, untamed landscapes.

Ten years later, the Hobbit trilogy (2012-2014), as well as Warcraft (Duncan Jones, 2016), took the same aesthetic stance while also benefitting from the technological advancements achieved in the intervening years. Popular Asian filmmakers (especially those from China and India), who have really only been seen in the west since the early twenty-first century, are enlarging the range of possibilities for portraying the fantastic. They don’t hesitate, for example, to intertwine the conventions of the supernatural with martial-arts sequences, as in Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Ang Lee, 2000), or the Detective Dee series (Tsui Hark).

Since the late 2000s, 3-D technology has inspired a new wave of projects. They tend to favor speculative genres that can get the most out of that new kind of illusion. James Cameron’s Avatar (2009), the first 3-D blockbuster, actually glorifies the magic of immersion. Access to the planet Pandora and its mystique of natural connection; which was rendered so magnificently in 3-D, is only possible for the paraplegic hero, Jake, through a high-tech avatar link unit, that projects him into the body of a 10-foot-tall Na’vi.

When Tim Burton “adapted” Alice in Wonderland (2010) into 3D, he introduced innovations into Lewis Carroll’s (or Carroll’s illustrator, John Tenniel’s) world. Some of those innovations drew on Burton’s own singular visual signature; others, on successful conventions established by Peter Jackson. Alice starts out by joining the ranks of Burton’s many young women in blue dresses. Later she becomes a warrior in silver armor, doing battle with a dragon amidst the remains of a demolished white tower that strongly evokes the ruins of Osgiliath.