The History of Enchanted Tales for Children

The bond between children’s books and fantasy has lasted for over a century. Although they are sometimes looked down upon, many books fuelling children’s imagination have come to be seen as classics.

Fantasy is very connected to a youthful audience, insofar as it is presented as a return to the enchanted tales that are considered particularly appropriate for them. A large swath of fantasy writing has always been addressed to children, from the genre’s English roots to contemporary transgenerational fiction.

“The Age of Childhood Sentiment”

England towards the end of the Victorian Era and into the Edwardian Era, at the turn of the twentieth century, experienced a “golden age” of children’s literature, to borrow the expression from the Scottish author Kenneth Grahame. Tolkien, on the other hand, referred querulously to the “age of childhood sentiment,” to describe that point in the history of mindsets in which a cultural construction of childhood became established. That construction would assign a specific form of imagination to very young children, one that would be idealized and quickly come to be seen as a kind of lost paradise. Fantasy contributes to glorifying an age that is closer to our origins, and thus to magic, the sacred, poetry and more: a refuge, in each of our lives, for the marvels of the beginning.

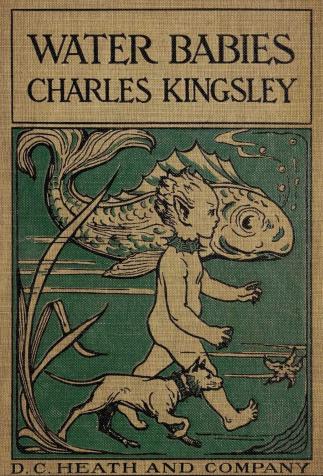

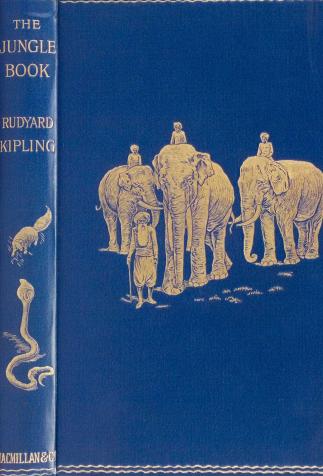

Fantasy from that era is still very much alive in our collective cultural memory, from Charles Kingsley’s Water-Babies (1863) to variations on the theme of animal fantasy in Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book (1894-95), Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908), and, somewhat later, A.A. Milne’s beloved Winnie the Pooh (from 1926), as well, of course, as that iconic young pair, Lewis Carroll’s Alice (Alice in Wonderlands, 1865, Alice through the Looking-Glass, 1871) and James Barrie’s Peter Pan (from 1902).

True to children’s books’ (and in fact all literature’s) dual goal of both “entertaining and educating,” the earliest fantasy offered children moral – and more importantly, religious – messages intertwined with a means of escape through imagination, which it raised to a place of honor. Carroll’s and Barrie’s founding, exemplary works both featured adventures in magical lands that could be reached from our own: Wonderland and Neverland.

English Tradition and American Renewal

The abundance of future “classic” fantasy books for children continued into the twentieth century in England. Many of them were written by women, like the prolific and talented Edith Nesbit (Five Children and It, 1902, The Railway Children, 1906); the Anglo-Australian Pamela L. Travers, famous for her Mary Poppins series (begun in 1934); and Enid Blyton. Best-known for her Famous Five series, Blyton started her career by rewriting Greek and Roman myths. She first came to the public eye in the 1930s with her Adventures of the Wishing-Chair and Enchanted Wood series, in both of which magical enchantment bursts into children’s lives, wreaking joyful havoc. In the following decades, lovely intimist books, like Tom’s Midnight Garden (Philippa Pearce, 1958) and Charlotte Sometimes (Penelope Farmer, 1969), brought different time frames together.

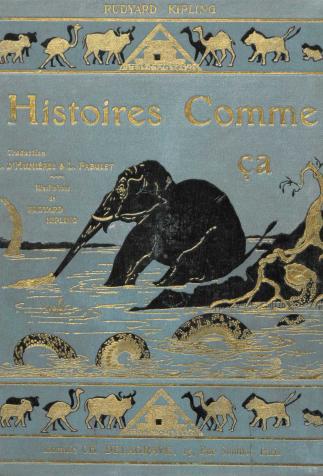

Alongside those books by women, male authors, writing for both children and adults, aimed for a harmonious balance between exalting the imagination and transmitting values. That was the case for Rudyard Kipling’s Just-So Stories (1902), J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937), and C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia (1950-1956). It is also true of T.H. White’s Arthurian tetralogy, The Once and Future King (1958), which is best-known for the first part, The Sword in the Stone. Originally published as a stand-alone novel (1938), it was later made into an animated film by Disney (1963).

In the United States, a parallel tradition became established; it is still thriving. The classic features of popular genre literature, with its reader-friendly, stereotypical characters, were far more apparent than in English fantasy, from as early as L. Frank Baum’s “Oz” novels. Starting in 1900, he churned them out an almost industrial pace. Plenty of low-cost publications (from dime novels to pulps) presented speculative tales, and young readers were one of their largest target audiences. Boys and girls each had their own genres.

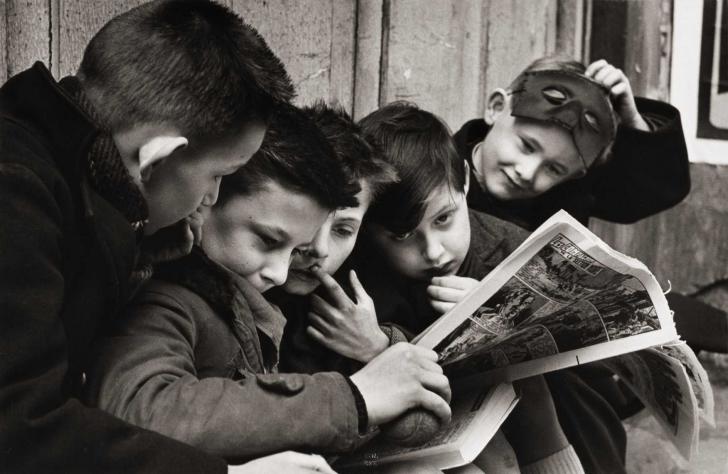

Fantasy also reached young audiences through other popular media: comics, for instance, drew on chivalrous heroism, whether medieval, as in Harold Foster’s Prince Valiant (since 1937) or rewoven into contemporary super-hero mythology. In the late 1970s and into the 1980s, both table-top role-playing games, like Dungeons and Dragons, and “you are the hero” book-games, which echo the genre’s codes for the needs of the book’s branching structure, expanded dramatically. Fantasy’s immense popularity with a young, often working-class audience went hand in hand with a certain depreciation of its reputation.

Small Animals and Young Magicians

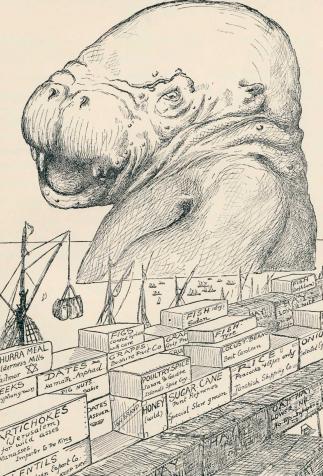

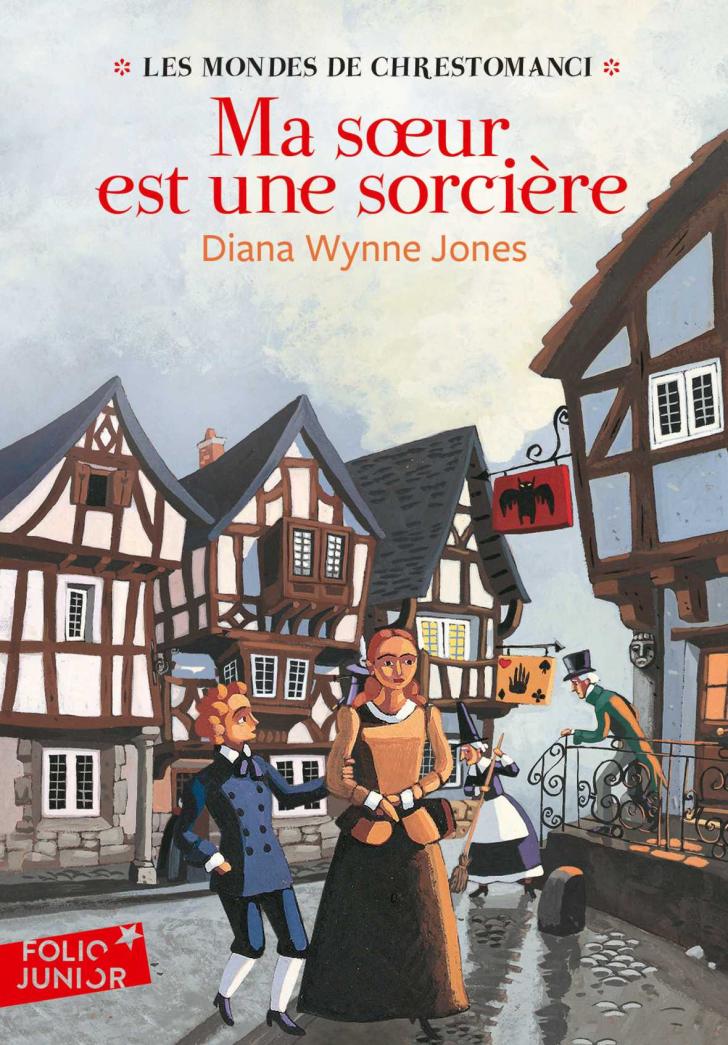

Except perhaps for the German author Michael Ende’s Neverending Story (1979), in which the magical elsewhere takes the shape of a book, fantasy for young people from went relatively dormant from the 1960s to the 1980s. Nonetheless, alongside singular bodies of work, like Roald Dahl’s, whose cruel humor scandalized people in its time (Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, 1964), broad sub-genres and narrative structures that still hold sway, irrigating today’s abundant production, were being established during that period. Young magicians were already going to witchcraft school in Jill Murphy’s Worst Witch (1974) and Anthony Horowitz’s Groosham Grange (1988), while Diana Wynne-Jones inaugurated the enchanter Chrestomanci’s adventure series with Charmed Life, in 1977.

Animal fantasy – which features societies of animals behaving more or less like humans, but in a natural setting or with attitudes specific to each species – continued to be a dynamic sub-genre, with Richard Adams’ Watership Down (1972) and its complex rabbit’s-eye view of world-building, followed by Brian Jacques’s many volumes devoted to the animals (mice, badgers) living inside a Medieval-esque abbey in Redwall (1986-2011). The vein has been making a comeback since the early 2000s, with works by Kathryn Lasky (the owls in the Guardians of Ga’Hoole, 2003-2013, which was made into a movie in 2010), and the quartet of three writers and an editor going under the collective pseudonym Erin Hunter (the clans of wild cats in the Warriors series, which was also launched in 2003).

At the turn of the twenty-first century, the “Harry Potter phenomenon” (J.K. Rowling (1997-2007) would shake everything up, leading to a massive reconfiguration of the publishing market as a whole. The whole industry skewed more towards children’s and young adult literature, sectors that have been expanding constantly ever since. More and more collections are being created, and more and more shelf space is being turned over to the branch and its breath-taking market shares. With the success of Peter Jackson’s adaptations of The Lord of the Rings during the same period, as well as the wide-spread growth of high-speed internet, the huge games market entered a new era. Children’s and young-adult fantasy suddenly reached far beyond its traditional boundaries, gaining new respect.