Faith and Religion in Fantasy Societies

Fantasy grants tremendous importance to the sacred. Far more than just window dressing, characters’ spirituality or religion often plays a crucial role in the plot.

The word “sacred” traditionally refers to anything that is outside of the ordinary or goes beyond basic utilitarian principles. Any sacrosanct object or concept whose legitimacy and superiority may not be challenged is considered sacred. Defining the sacred is therefore one of the founding elements of any society. What a populace considers sacred reveals its beliefs, customs and history. Thus, a people’s relationship to the sacred is actually a way of defining its identity.

Do the Heroes Pray?

So it makes sense that fantasy, which aims to create lush and often complex worlds, would also grant great importance to the sacred. More than just window dressing to define a society, the characters’ spirituality, and the religions established in their world, often play a crucial role in the plot. To bring a fully realized fantasy world compellingly to life, authors and creators can’t settle for an exotic landscape, endearing characters, and an unusual plot; they also need to account for spiritual issues in the worlds they create. What are the world’s religions? Does the concept of the sacred correspond to personal practices, or is it more institutionalized? Do the heroes pray, and if so, to what end? Defining the sacred in a work of fantasy often contributes to structuring the plot, as well as introducing the powers that rule that particular world, which often have an impact on the hero’s quest.

Humanity’s Great Questions

Although it offers exciting stories in fascinating settings, fantasy is still founded on the major philosophical questions that occupy humanity, including the relationship between body and mind, the existence of a divine power, how we are affected by the passage of time, and of course, life and death. Fantasy often includes apocalyptic themes, with threats looming over the world and their possible consequences to society. Whether the point is to save the world from destruction, get life back to normal, or, on the contrary, to learn to live with the repercussions of chaos, the protagonists often turn towards spirituality to help them with their task – or, conversely, are required to labor in a godless, lawless world.

Life, Death, and Everything Else

The issue of mortality and immortality is a favorite with fantasy authors, who explore the influence and issues at stake in the passage of tiem, as well as the concept of free will and fate (The Wheel of Time, Robert Jordan and Brandon Sanderson, 1990-2013). Following the model of founding myths, a number of works make use of prophesies, which are portrayed as superior but often misleading powers guiding the plot and holding readers’ or spectators’ interest. This play between reality and myth, history and legend is at the heart of a great number of tales (The Kingkiller Chronicle, Patrick Rothfuss, since 2007).

Each individual work, as well as each wider world – such as those created by J.R.R. Tolkien, Terry Pratchett, Ursula K. Le Guin, Marion Zimmer Bradley, and George R.R. Martin – has its own religious workings, with its own spiritual implications. Death is not, therefore, necessarily synonymous with complete disappearance: the rules can be entirely redefined in order to create new narrative possibilities. Consequently, characters’ attitudes towards life, death, and life after death can be overturned, as can their relationship to the divine and the supernatural.

New Deities

Because of the diversity of themes addressed in fantasy, the sacred isn’t limited to traditional monotheistic or even polytheistic deities. Fantasy creates new, superior beings, gods, demons and fairies, who, following the model of the ancient epics, often meddle in the hero’s path. Neil Gaiman’s novel American Gods (2001) even considers the sacralization of concepts and techniques in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The focus is on those related to means of communication, which popular fervor turns into forms of the divine. In fantasy, gods’ and mortals’ fates are often closely intertwined.

From Spirituality to Magic

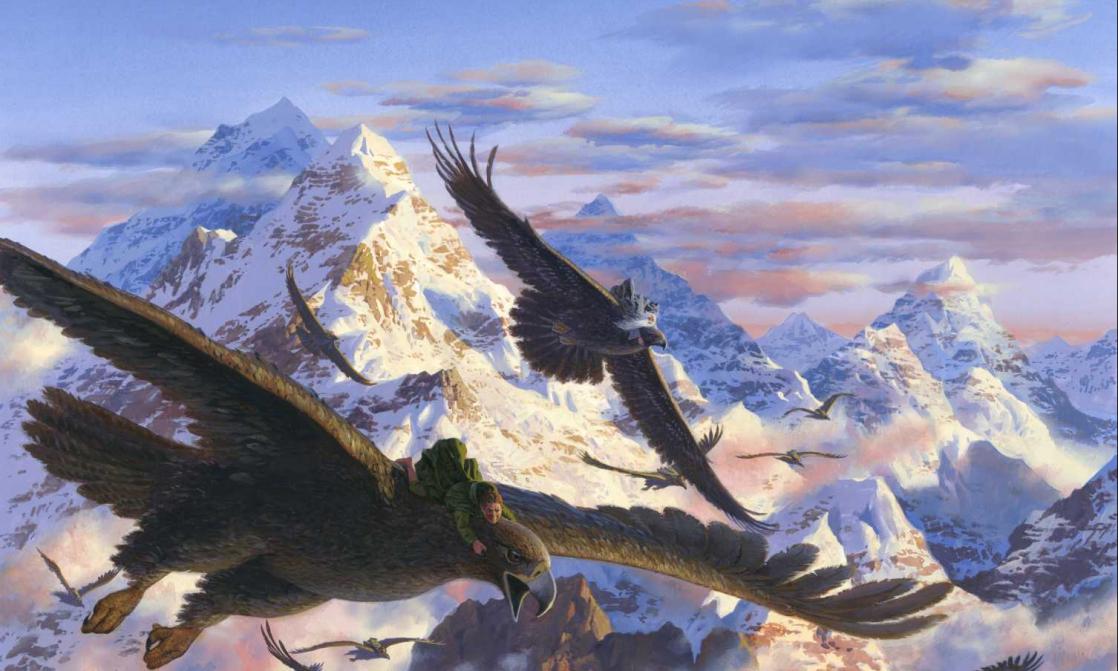

Although spirituality isn’t always synonymous with either institutionalized religion or more individual practices, by its very nature, fantasy tends to feature external manifestations of faith that fuel the story. Magic is frequently portrayed as one of the markers of that spirituality: prayers and incantations, or sometimes exceptional gifts, tend to be how witches and wizards perform supernatural deeds. Thanks to those supernatural phenomena – and a keen sense of timing – some magicians or superior beings turn into veritable incarnations of classical antiquity’s deus ex machina. Their skill at resolving impossible situations at the last minute gives them a nearly divine status in the story, like Tolkien’s Great Eagles.

Intermediaries of the Gods

These magical-religious practices correspond to a kind of transcendence. Favored characters, propelled by an innate gift, hard work, or more often, a combination of the two, manage to establish spiritual relationships with higher elements. They enter into communion with the gods, achieve peaceful harmony with the world, explore the secrets of time, etc. Fantasy appeals frequently to characters with transcendent abilities that allow them to enter into communication with supernatural beings. That is the case for prophets, seers, and various oracles – if not to free themselves from the laws of physics by accessing superior knowledge. Thus they can control minds or travel through space and time in an instant. In fantasy, transcendence, in the sense of access to a higher power through spirituality, makes itself manifest in ways that are not only visible, but often quite striking. More than just an element of social construction, faith becomes an engine driving the plot, guiding the characters through their adventures – or, on the contrary, foiling their projects.

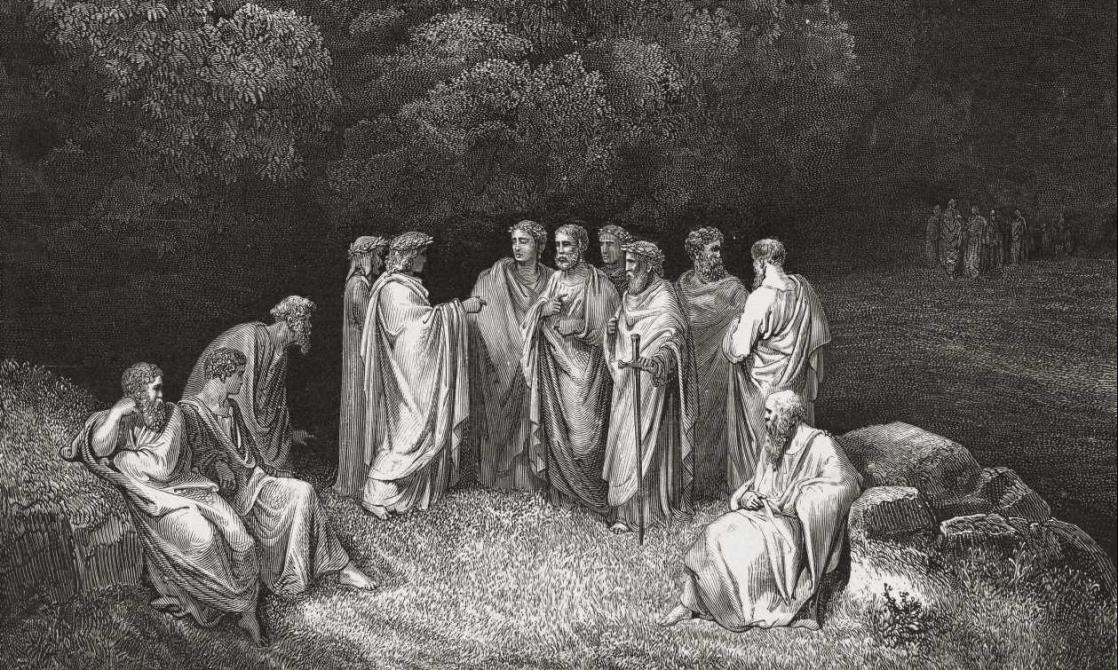

Still, spirituality is often restricted to characters who are entirely devoted to it. Priests, druids, and magi do play critical roles as intermediaries between the world as it is described and the spirit world. Yet alongside them, most of the other characters tend to shy away from sacred practices. While faith can be shared by all, demonstrations of it through rites and prayer are generally the domain of specific characters who are entirely focused on spirituality and who interpret the sacred for ordinary mortals. So quite often, fantasy actually reprises a division of labor that is inspired both by traditional social practices and by role-playing games. Depending on the rules and goals of the chosen story, various classes of characters may assume a religious or spiritual role: druid, spell-caster, magician, monk, priest, priestess or more.

From Faith to Institutions

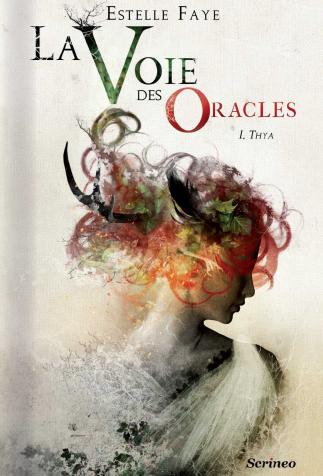

Fantasy tends to pit personal spirituality, which is generally portrayed as pure and beneficial to characters, against institutionalized religion, which is often shown as a source of corruption, destruction, and sometimes even fanaticism (La voie des oracles ‘The Oracles’ Way,” Estelle Faye, since 2014). That’s why the context of the growth of Christianity in Europe in late Antiquity and the Middle Ages so frequently inspires authors, who use religious themes as a starting point for exploring issues such as authority, community, and tolerance. In a similar vein, the question of specifically feminine spirituality or magic, as opposed to their masculine counterparts, is often raised, either through a clear distinction between genders (Les Illusions de Sav-Loar, Manon Fargetton, 2016) or an attempt to reconcile their religious aspirations (The Avalon Series, Marion Zimmer Bradley and Diana L. Paxson, 1983-2009).