Doors Between Worlds

Fantasy heroes visit secondary worlds, and to pass between universes they use portals, symbolic “access points,” or simply the intervention of magic.

Many fantasy tales open directly in the world and/or time period in which the story will unfold: that style is known as a “single world” structure. But other stories prefer to portray the passage from one world (our own, usually) to another: the latter, a world of magic, marvels, dangers, adventures, stories (The Neverending Story, Michael Ende, 1979), dreams (Mirror Dreams, Catherine Webb, 2002), childhood (Peter Pan, James Barrie, 1911), and/or images of paradise lost or found.

Passages to Create

In the “two-world” structure, the narrative arc is triggered by various ways of passing between worlds. In Les fictions de jeunesse (“Fiction for Children,”, 2013) Christian Chelebourg sorted them into categories named for elements from classic children’s fantasy books: “the white rabbit model” (when the hero follows a guide), “the chess-board model” (when there are game rules to follow, as in Jumanji; Chris Van Allsburg, 1981, adapted into a film and an animated series) and, finally, “the tornado model,” when major upheaval whisks the hero away from their comfortable routine, like the tornado that plucked Dorothy out of Kansas and deposited her in Oz in The Wizard of Oz (1900).

Two-world plots are more often aimed at young readers, probably because they allow for a more progressive transition from the familiar world, which parallels the imaginary transportation that fiction aims to achieve. In the same way, in early fantasy, dreams were often used to “justify” or “rationalize” passages to other worlds, in a way that may seem artificial nowadays, but which seemed both necessary and realistic then. That’s how John Carter reached Pellucidar (The Princess of Mars, Edgar Rice Burroughs, 1917) while E.R. Eddison’s Worm Ouroboros (1922) starts with a sort of prologue in which the narrator, Lessingham, explains that he is dreaming about another world before permanently vanishing from the novel that takes place there.

Finally, “multiverses” offer an infinite number of parallel universes – like the potentials that are loosely based on quantum physics – for us to explore alongside the hero. They can be found in the oeuvres of Michael Moorcock, with his intertwined Eternal Champions cycle, of which Elric of Menilboné is the most famous incarnation (since 1961); Philip Pullman, with his His Dark Materials trilogy (1995-2000), and Lev Grossman’s Magicians (since 2009). Sometimes one central reality that keeps everything coherent needs to be preserved. For Stephen King, it’s The Dark Tower, which lends its name to the series (eight novels since 1982); in Roger Zelazny’s Chronicles of Amber (since 1970), it’s the world of Amber, which all other worlds are mere shadows of.

Physical Access Points

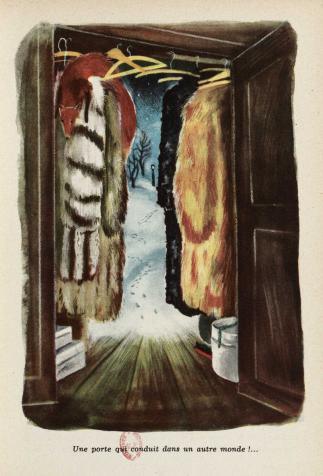

Fantasy authors have dreamt up all sorts of portals to other worlds. The most iconic of them is surely the eponymous “wardrobe” from C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950). This seemingly ordinary piece of furniture is in fact a portal to a magical elsewhere that leads the Pevensie siblings to the perpetual winter of Narnia. In the following volumes of his series, Lewis would introduce myriad other portals: a seascape painting in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, an Underground platform in Prince Caspian, the surface of water in The Magician’s Nephew, and others, concluding with a deadly train crash in The Last Battle.

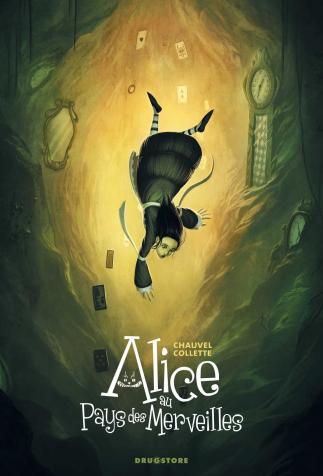

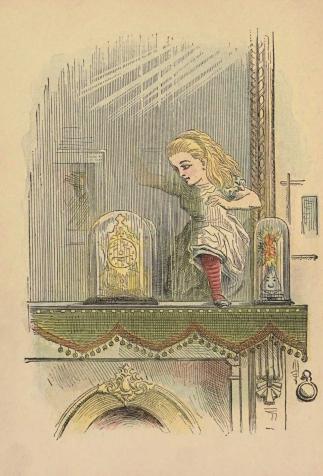

While there can be physical passageways, such as holes (like Alice’s rabbit hole, 1865), doors (in Neil Gaiman’s Stardust, 2001) or windows (as in Philip Pullman’s The Subtle Knife, 1997); secret alleyways (leading to the hidden wizarding world tucked alongside our own, like the iconic Platform 9¾ in Harry Potter, 1997-2007, or towards the world of Cités obscures (Obscure Cities, or Cities of the Fantastic) in Schuiten and Peeters comic-book series, since 1983), some magical objects can also act as portals. They might be mirrors (as in Lewis Carroll’s second volume of Alice’s adventures, Through the Looking-Glass, 1871, and Cornelia Funke’s Mirrorworld series, which was inspired by Grimm’s fairy tales (since 2010) or tarot cards (in The Dark Tower and The Chronicles of Amber). Books (in The Neverending Story, and the video game Myst, 1993) are, of course, also favored interfaces for transportation.

Toppled by Magic

Magical powers can also transport characters, whether they are the victims of spells – as is often the case with Elric, in Michael Moorcock’s eponymous cycle, they take advantage of a magical intervention – like the Canadian students taken to Fionavar in Guy Gavriel Kay’s Fionavar Tapestry trilogy (1984-1986), or the characters’ themselves accidentally activate a gift they possess, unbeknownst even to themselves, like Camille/Ewilan who discovers the “sidestep” or “great step,” (a form of teleportation), when she nearly gets run over by a truck at the beginning of Pierre Bottero’s tales of her adventures (La Quête d’Ewilan (Ewilan’s Quest), 2003).

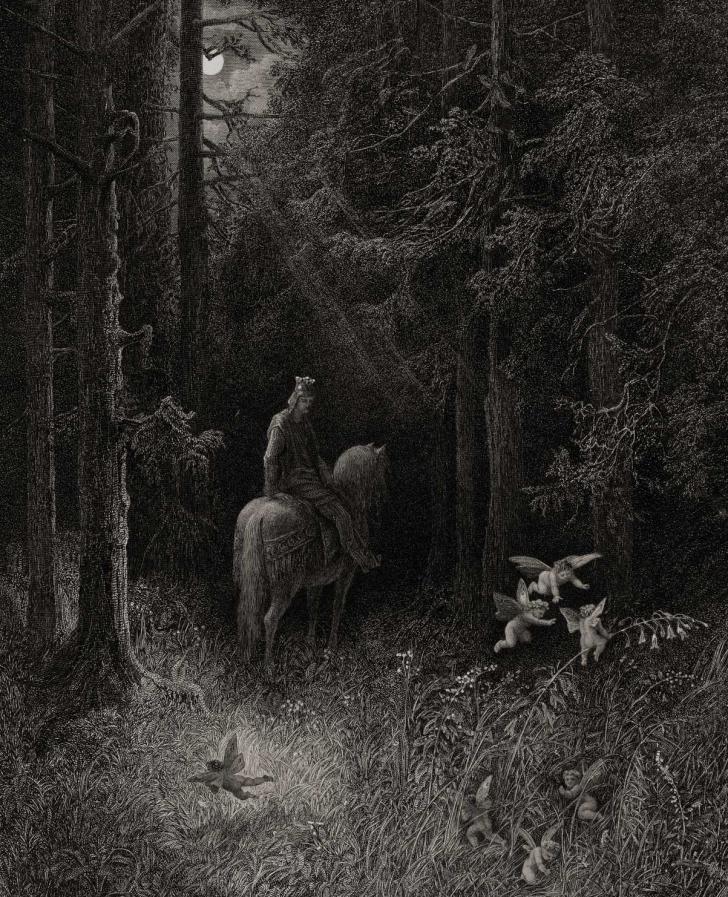

Lastly, the transition can be gradual, introducing us to a fairy world within arm’s reach of our own. So the Knights of the Round Table slipped into other worlds while chasing dragons and other enchanted creatures into the heart of the forest. Sometimes, thanks to a move or a journey, the hero enters into communication with the spirits of nature that had been concealed until then, as in Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro and Spirited Away (1988, 2001), Robert Holdstock’s Mythago Wood cycle (since 1984) and Brandon Mull’s Fablehaven (single 2006). A single contact with faerie transforms an ordinary life for good in both J.R.R. Tolkien’s Smith of Wootton Major (1967), Ellen Kushner’s Thomas the Rhymer (1990), and Neil Gaiman’s Stardust (1999).

Reflections of our desire for escapism, fantasy’s other worlds also acknowledge its limits: in the end, as in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, one must “close the windows” though it can be at the price of lost love, and overwhelming nostalgia.