The Inklings: The Rebirth of English Fantasy

Having been formed in England in 1930, this informal literary discussion group comprised the future crème de la crème of fantasy writers, including J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S Lewis. The group contributed greatly to the genre’s revival by encouraging and influencing its members.

While fantasy was born in late-nineteenth-century England, the genre as we now know it was defined by the work of an informal group of writers, the two most famous of whom were John Ronald Reuel Tolkien and Clive Staples Lewis. The club, which was founded at Oxford in the early 1930s, was known as the Inklings.

A Legendary Group

The punning name comes from the actual meaning of the word inkling (a vague notion or suspicion about something), but was also a pun on the words ink and link, making it perfect for a writers club. That type of all-male club was a popular way to socialize for Englishmen. Tolkien had in fact previous belonged to another university club, the Coalbiters, which was dedicated to studying Norse languages and their medieval literature. Throughout the 30s and 40s, and for some members, until Lewis’s death in 1965, the Inklings met informally more or less weekly, either in Lewis’s rooms at Magdalen College or at lunchtime at various local pubs, most famously The Eagle and Child, which was familiarly know in the Oxford community as The Bird and Baby. They would get together to chat, drink, smoke, and crack jokes, but above all, as writers, to read what they were working on out loud for the others to comment on and criticize.

Although they are less well-known, Charles Williams and Owen Barfield were also key members of the group. Many other men – including C.S. Lewis’s brother Warren; Hugo Dyson, a Shakespeare scholar; J.R.R. Tolkien’s youngest son, Christopher; and Roger Lancelyn Green, author of mythology books for children and a former student of C.S. Lewis’s – also attended more or less frequently.

Tolkien and Lewis

The mutual influence followed by friendly rivalry between Tolkien and Lewis was woven in the context of Oxford between the two World Wars. It was also the basis of the fantasy “renaissance.” While the literary genre existed before Tolkien, his work was so influential that it cast a shadow over everything that had preceded it. Although he can not be said to have invented fantasy, Tolkien truly did “reinvent” it, insofar as his oeuvre stands as a model for the entire genre.

Although he is undoubtedly less well known than Tolkien, C.S. Lewis is still quite famous, both for his role as a defender of a comforting Christian faith and, above all, for his Chronicles of Narnia (1950-1956), which are classics of children’s literature.

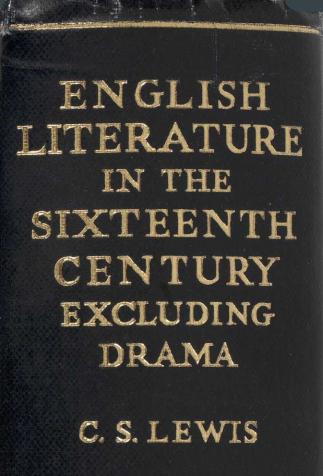

J.R.R Tolkien (1892-1973) and C.S. Lewis (1898-1963) had similar backgrounds, which drew them together. They both lost their mothers while young, belonged to the generation that suffered greatly in World War I, and had started roughly similar careers as medieval scholars. While Lewis came to specialize in medieval literature and the Renaissance, Tolkien chose to study philology of the Anglo-Saxon language. In 1925, they were both elected Fellows at different colleges of Oxford University.

A Conflict Born from Religion

Religious debate and the idea of using their fiction to reflect their ideas about the sacred would first unite them before eventually coming to divide them. Having abandoned his Anglican upbringing as a young man, Lewis regained his faith in the early 1930s, largely through discussions among the Inklings. Tolkien had been converted to Catholicism, a minority religion in England, by his mother, who had died young. He was largely responsible for reconciling Lewis with religion, bringing his passion for mythology and his desire to write in the Romantic style into communion with holy writing.

Their religious differences began to accentuate after that, as Lewis soon became a zealous promoter of the Church of England. The Christian message in his novels was clear, rather too much so for Tolkien, who opposed any allegorical interpretation or unequivocal correspondence between his own oeuvre and history or literature. More broadly, Tolkien was discreet while Lewis became a popular public figure. The difference also shows up in the quantity of work they each published. While Lewis has dozens of tales and essays to his name, Tolkien had only two novels published during his lifetime.

The two gradually grew apart over the years after World War II, the period in which each of them would write their most famous work. But the roots of both men’s novels still lie in a plan they devised together to divvy up the spheres of fantasy: Lewis would get space, which he explored in the Cosmic Trilogy (1938-1945), and Tolkien, time.

When Esotericism Influenced Fantasy

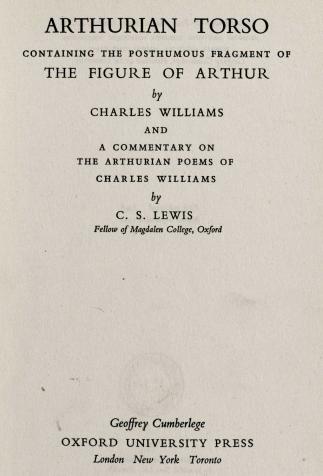

Charles Williams (1886-1945), novelist, poet, playwright, and essayist, also won fame in the fantasy genre. His best-known novels, War in Heaven (1930), Descent into Hell (1937) and All Hallows’ Eve (1945), can be described as fantasy tinged with religiosity. In War in Heaven, the Holy Grail reappears in England; Descent into Hell takes place during rehearsals for a play in a London suburb, during which the characters will experience supernatural events that will lead them either to salvation or to damnation. Williams shared his Inkling comrades’ fervor for the Middle Ages, retelling the Arthurian legend in a cycle of hermetic poems, Taliessin through Logres (1938) and The Region of the Summer Stars (1944).

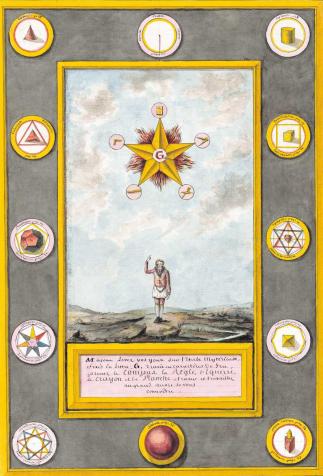

Although he has been somewhat forgotten nowadays, the philosopher and critic Owen Barfield (1898-1997) and his linguistic theories (Poetic Diction: A Study in Meaning, 1928) influenced Tolkien, to whom the idea of a primordial unit of language appealed greatly. Barfield’s reputation suffered from a certain lack of rigor in his etymological intuition, as well as from his association with the ideas of Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), the Austrian founder of anthroposophy, a “spiritual science.” Some of his ideas have been given a second chance in recent years, because Steiner also theorized some of the principles of bio-dynamic agriculture. Charles Williams was attracted to esotericism, too, but he forged his own theological convictions. They were founded on the heterodox concept of “co-inherence,” an interdependent network between the material and spiritual worlds and between individuals, in which all of our actions reverberate spiritually in ever-expanding waves.

Religious worship plays a key role in the history of the Inklings, as well as of each of its members individually. They revived the bond, which was already flagrant in the Victorian era, between fantasy as a mode of artistic expression and intense yet individual, often even unorthodox, spiritual concerns. They saw fiction as a path providing access to other worlds.