The Iliad and The Odyssey: The Wellsprings of Fantasy

Dating back to nearly three millennia ago, The Iliad and The Odyssey are the wellsprings of modern fantasy. Despite their age, the influence of those two epic poems on contemporary writers has never run dry.

Written to Last

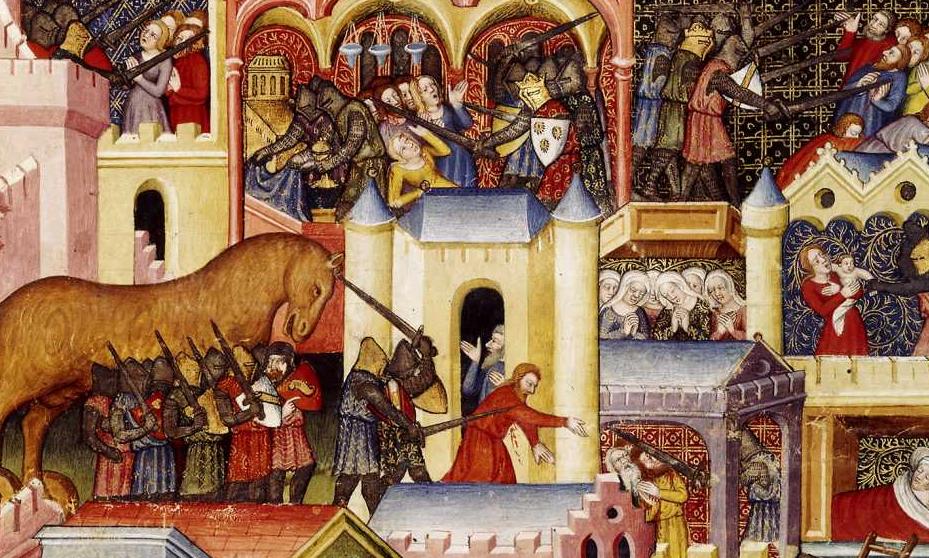

The Iliad and The Odyssey, the two Greek epic poems attributed to Homer (sixth century B.C.E.), relate different parts of the “Trojan War cycle” (also widely known as the Epic Cycle), which encompasses both the Trojan War and its consequences. The conflict, set around the late twelfth century B.C.E., starts with the abduction of Helen, the wife of Menelaus, King of Sparta, by Prince Paris of Troy. Agamemnon, brother of the wronged spouse, gathers an army composed largely of Greek kings, including Achilles, a Thessalian prince, and Ulysses, King of Ithaca. The Greek army lays siege to Troy for ten years, eventually winning the final battle thank to Ulysses ruse and his Trojan horse. Although they are separate works, both epics were destined to become landmarks of literary history.

The central theme in The Iliad is Achilles’s anger. His pride having been wounded by Agamemnon, who abducted his slave, Briseis; the hero refuses to fight. But when Hector kills his closest friend, Patroclus, Achilles takes up arms once more to avenge Patroclus’s death. He kills Hector in a duel, then drags the body around Patroclus’s tomb. The poem ends with Hector’s funeral, after Achilles has finally agreed to give the corpse to King Priam. At this point, The Iliad becomes the archetypal war epic: the genre’s main ingredients are the clash between two nations, a superhuman hero, and a heroic friendship in the mold of Achilles and Patroclus. The genre generally also includes a supernatural dimension, as here, where the narrative is divided between the humans’ actions and the twelve Olympian deities’ meddling in human affairs.

The Odyssey describes Ulysses ten-year journey around the Mediterranean after the fall of Troy. After many hardships and trials, he is finally able to return to Ithaca. His wife, Penelope, and son, Telemachus, have awaited him faithfully, but the hero must go into battle to reconquer his kingdom. The pitfalls and traps that Ulysses and his crew have to avoid or overcome fill the text with magic and the supernatural. He must resist the lure of the fruit of the Lotus-eaters’ that causes his crew to forget their desire to sail home, the temptation of the Sirens’ song, and the nymph Calypso’s offer of immortality, as well as contending with a man-eating Cyclops, and saving his companions from the magic of the enchantress Circe, who turned them into swine.

Founding Epic Poetry

Those two epic poems have been inspiring literature and the arts since Antiquity. Fantasy writers have been drawing on this shared cultural wellspring, without necessarily having read The Iliad or The Odyssey firsthand. Often they will have read “relay books” that have impressed their vision of the Trojan War and its heroes on the popular imagination. Many fantasy writers reprise the Homeric epics’ plot more or less faithfully, by transposing them to the author’s own unique world. Like The Iliad, the great high fantasy (a.k.a. epic fantasy) series feature conflicts and wars in which a nation’s – or even an entire world’s – fate is at stake (The Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien, 1954-1955; A Song of Ice and Fire, G.R.R. Martin, from 1996; they borrow numerous themes from the epics: battle scenes in Hordes (Laurent Genefort, 2007-2010); a Homeric catalogue in Chasse royale (“Royal Hunt,” Jean-Philippe Jaworski, 2015), and the duel between the panserbjørn bear Iorek Byrnison and the usurper Iofur in Northern Lights (a.k.a. The Golden Compass, Philip Pullman, 1995).

The Odyssey offers a model of archipelago-world creation in which each island possesses its own unique appearance, inhabitants and social rules, as in Earthsea (a.k.a. The Earthsea Cycle, Ursula K. Le Guin, 1964-2001) and The Dream Archipelago (Christopher Priest, 1999). The Odyssey has inspired countless adventure tales of naval exploration of worlds, including Spirited Away (Hayao Miyazaki, 2001), which reprises the concept of turning humans into swine.

The Classics Updated for Our Times

Some rewritings are more directly engaged with the Homeric epics, challenging the praise they heap on military heroics. Madeline Miller’s novel The Song of Achilles (2011) is based on the long-debated belief that Achilles and Patroclus heroic friendship was actually a love story. Marion Zimmer Bradley, in The Betrayal of the Gods (1987), narrates the Iliad from the point of view of the young priestess Cassandra, wo was trained by the Amazons. Last, but not least, Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad (2005) and Madeline Miller’s Circe (2018) feature a comparable counter-narrative practice by confiding the narrator’s role to women who were confined to the margins of the The Odyssey. In this way, fantasy is continually adapting the Homeric epics to contemporary ideas.