From Ancient Greece to Fantasy

Although fantasy is a modern genre, its roots can be found in the distant past. From The Iliad to The Metamorphoses, from Greek gods to combative heroes, the foundations are no different from those that inspired authors millennia ago.

Draw on shared cultural foundations… the better to make them one’s own. Arguably, that is the very essence of fantasy, which draws inspiration from ancient myths and epic poems to create tales that are both original and comfortingly familiar at the same time. The founding myths of the western imagination offer a wealth of resources for the genre, with valiant heroes, epic battles, adventures overflowing with unexpected plot twists, beings with extraordinary powers, and fabulous creatures.

Like classical antiquity’s epic poems – many of whose features it reprises – the fantasy genre intertwines mythology and history in an elevated, hyperbolic style, in order to glorify brave heroes’ great deeds. While The Iliad (eighth century B.C.E.) focuses on military action and heroic battles in its description of the Greek army’s siege of Troy, The Odyssey (eighth century B.C.E.) describes Ulysses’ convoluted journey around the Mediterranean, offering readers a travel narrative filled with fabulous adventures and studded with extraordinary creatures.

Heroes Confronted with Good and Evil

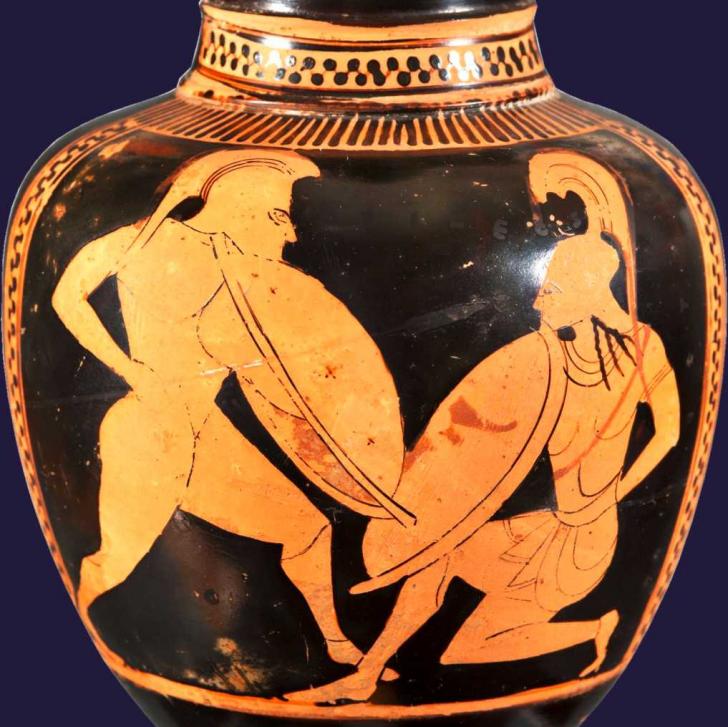

These elements are especially present in “high fantasy,” which is characterized by an epic confrontation between Good and Evil. Like the heroes of the classical epics, fantasy characters can achieve great deeds alone or as part of a group of (mostly male) heroes. The hero is portrayed as an exceptional character. Achilles, the protagonist of The Iliad (eighth century B.C.E.), the son of a goddess and a mortal, is a demigod. As a brave and powerful warrior, he is an icon, incarnating the qualities all men should strive for: courage, physical strength, and skill in combat. Yet Achilles is threatened by his own hubris, or excessive pride.

As in epic poetry, many fantasy heroes have exceptional ancestry, and must prove themselves on the battlefield. Even when that is not the case – Frodo Baggins, the hero of The Lord of the Rings (J.R.R Tolkien, 1954-1955), is nothing like Achilles – they are generally engaged in an epic struggle for positive values, like freeing an entire populace, saving their friends or overcoming the forces of evil. To achieve that, they use both their physical strength (Conan the Barbarian, R.E. Howard, 1932) and intellectual prowess, like Tyrion’s ruse (A Song of Ice and Fire, G.R.R. Martin, from 1996), as well as key human values such as honor, loyalty and friendship.

Subtly drawn characters

Fantasy not only borrows epic poems’ narrative models, it is also inspired by their portrayals of human relationships and their subtly drawn characters. Despite the black-and-white plots, which appear to be simplistically pitting the “good guys” against the “bad,” epic poems are often founded on tremendous subtlety: Achilles, Ulysses and Hector (The Iliad, (eighth century B.C.E.) are all still celebrated as valorous warriors, yet they have their own distinct character traits, and are not interchangeable. In a similar way, Bilbo’s heroism (The Hobbit, J.R.R. Tolkien, 1937) is quite different from Arya’s (A Song of Ice and Fire) or Thrall’s (World of Warcraft, from 2004 on). Sauron’s and Saruman’s dreadful motivations differ dramatically (The Lord of the Rings). Based on shared conventions that aim to glorify humanity and social ties, fantasy integrates epic characters’ subtlety as well as their strength.

Music, Magic and Marvels

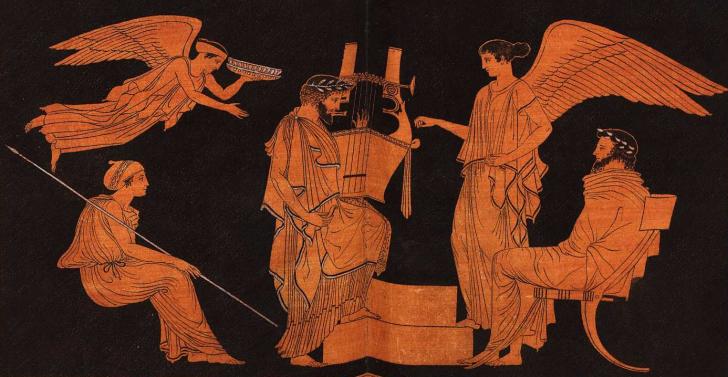

The importance granted to songs and musicality in fantasy – like the songs and poems Tolkien includes in his books – is not insignificant. Originally, epic poetry, which recounted the adventures and achievement of a hero, a group of knights, or an entire populace, was often set to music. Ancient Greek aoidoi (“singers”), and medieval bards and troubadours spread and popularized those texts from the oral tradition, contributing to their success across Europe. Whether sung or chanted, epic poems were recited with musical accompaniment. By the same token, works of fantasy often include songs or sung poems that complete and enhance the narrative world (Le Donjon de Naheulbeuk, by John Lang, a.k.a. "Pen of Chaos", 2001).

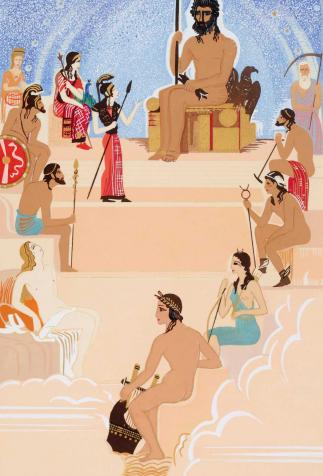

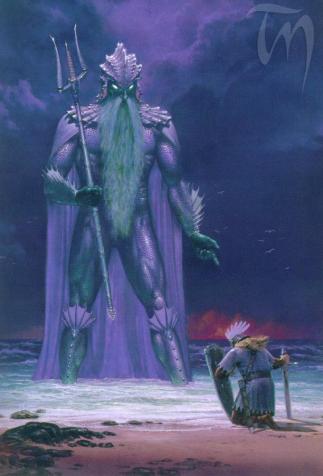

As in the classical era’s epic poems, magic and the supernatural play a key role in fantasy. In Virgil’s Aeneid (first century B.C.E.), the plot is divided between humans’ actions (the heroes’ battles, political in-fighting, etc.) and divine activity (the gods on Mount Olympus choosing to assist one hero or, on the contrary, place obstacles in another’s path). Magic is considerably more common in fantasy than in its role models from Classical Antiquity or the Medieval Era, to the point that it is viewed as a founding component of the genre, as in Earthsea, (Ursula K. Le Guin, 1964-2001).

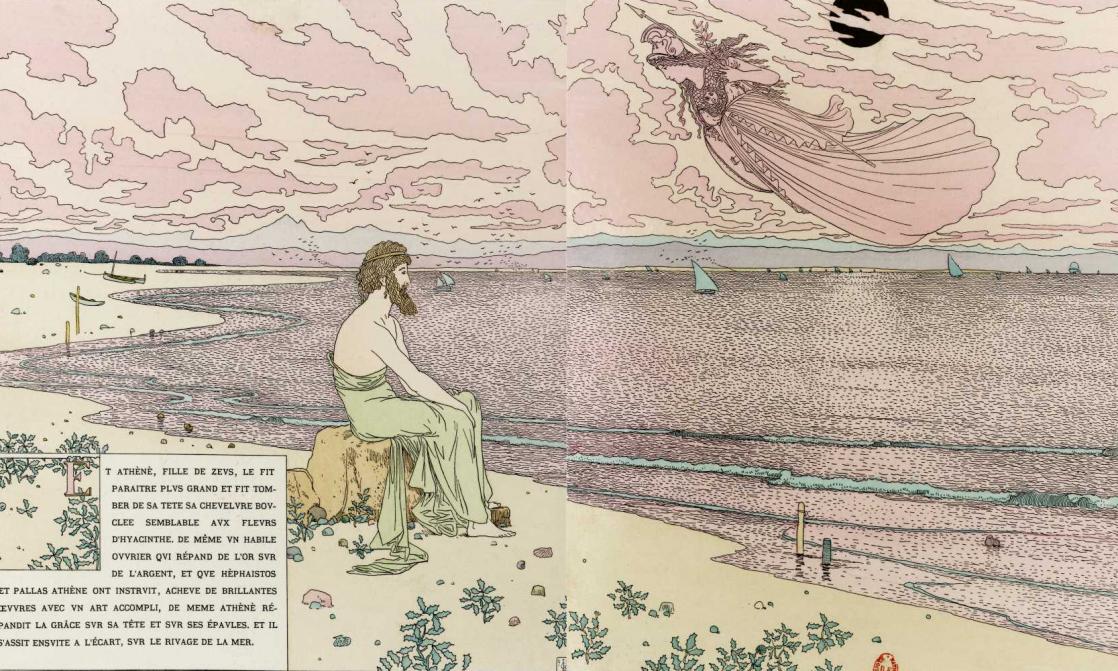

Finally, fairies, witches and wizards also play a leading part, absorbing and developing the role originally granted to the supernatural. Based on the model of myths, fantasy loves to feature divine or supernatural intervention via the appearance of superior beings endowed with endearingly human qualities and flaws. Those beings involve themselves in the heroes’ quests, whether to assist them or foil their plans. Inspired by a beloved trope in classical mythology, magical objects, monstrous creatures (The Legend of Zelda, Nintendo, since 1986), and even a hero’s own metamorphosis can also come into play.

The Gods’ Influence on the World

Certain fantasy tales featuring the creation of the world and the gods (The Silmarillion, J.R.R. Tolkien, 1977, posthumous publication) and the divinities’ direct impact on human societies (The Belgariad, David Eddings, 1982-1984) are more directly connected to classical cosmogonies and theogonies. Founding myths allow us to impose structure on the world and to explain its mysteries; fantasy reprises that, giving birth to coherent and complete worlds (Lanfeust des Étoiles, (Lanfeust of the Stars), Christophe Arleston and Didier Tarquin, 2001-2008). The divine, humane and supernatural spheres often collide, whether peacefully or more conflictually. Even more so than in epic poetry, ancient myths grant human heroes the lion’s share of the limelight, observing divine affairs for their own sake, in addition to considering the influence they might wield over mere mortals.

As in those myths, some fantasy writers choose supernatural beings as their heroes (Good Omens, Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman, 1990). Whether the human beings who feature in the stories believe in divine intervention or not, integrating supernatural beings and their magical powers opens up a broad range of new possibilities for fantasy writers.