Tolkien: A Master of Fantasy

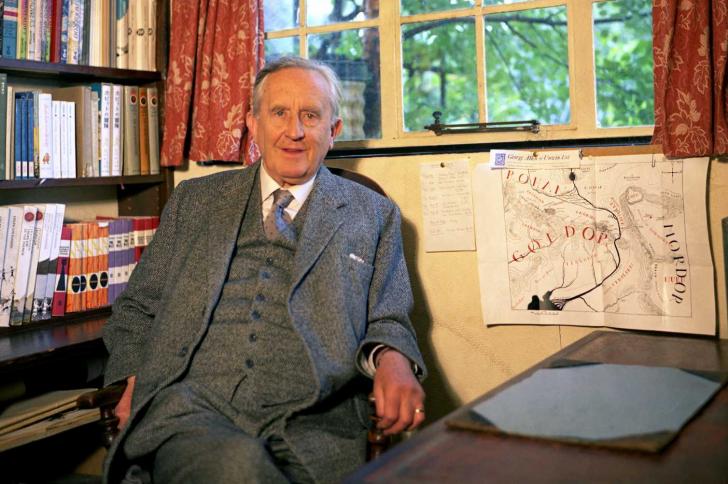

Seen as one of the greatest fantasy authors ever, J.R.R. Tolkien actually published very few books in his lifetime. It is his son Christopher who enabled fans to discover the full breadth and depth of his oeuvre.

Unexpected success

As the author of the three volumes of The Lord of the Rings (1954-1955) and the creator of a secondary world, “Middle-earth,” the central continent of Arda, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (1892-1973) now reigns supreme over the history of the fantasy genre. His main motivation for creating that world was to be able to bring the languages he had already invented to life. Wanting to offer them a setting where they could be spoken, he was determined to make that setting as complete, coherent and compelling as possible.

Although his first attempts at non-academic writing – poetry about the Elf people that was directly connected to his experiences during World War I – date back to 1916-1917, it would be another twenty years before his first work of fiction was published. Originally written for his own children, The Hobbit (1937) was an immediate hit in both Great Britain and the United States, which led his publisher, Stanley Unwin (who was succeeded by his own son, Rayner Unwin), to commission a sequel with the same endearing little characters.

Insisting on Writing for Adults

Although he wished to grab the chance offered to him, he was bothered by the chasm between his short novel and the poetic mythology of the immortal elves – the true essence of his work in his own eyes. So Tolkien decided to attempt a synthesis of the two sides of his inspiration, and to challenge his label as a writer of “children’s books.” In The Lord of the Rings (1954-1955), he showed the world what he was capable of.

Between those two classics, Tolkien hardly published anything. The medieval fable, “The Farmer Giles of Ham” (1949) being the sole exception. The publisher Allen & Unwin decided it to bring it out as a stand-alone volume, with illustrations by Pauline Baynes.

What’s more, the “sequel” his publisher had commissioned isn’t really one. Far longer and more complex, the Lord of the Rings trilogy is no longer addressed to the same readership. The relatively innocuous ring from The Hobbit has turned into a powerful symbol of the corruption of Evil, and the main character’s quest includes myriad ramifications and characters that become key for a time. Reflections on greed and the temptations of power diffract into a far subtler, infinitely less simplistic “good vs evil” whole than is often recognized.

The Lord of the Rings has in fact been interpreted in many different ways, which attests to its hermeneutic scope. Read as an allegory of that conflict shortly after World War II, and a pacifist and ecological manifesto when it turned into a cultural phenomenon in the United States in the 1960s, the text is also imbued with Catholicism. Conceived by Tolkien as a new Gospel, it is at heart a tale of how, even when everything seems hopeless, Light will overcome darkness in a final reversal, the “eucatastrophe.”

An Entire World Behind the Books

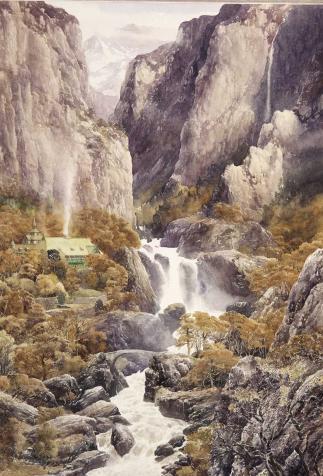

Busy with his career at Oxford and his family, Tolkien never published anything else about Middle-earth in his own lifetime. He did however, edit the enormous mass of material he had been producing for decades: the poems, myths and stories of Arda, from its creation from the music of the Ainur to Sauron’s scheming against the elf, dwarf, and human races sheltering in Middle-earth millennia later.

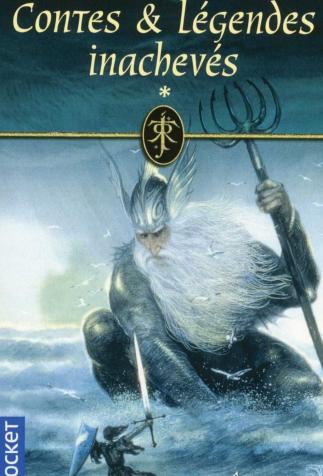

These texts, which taken together are known as Tolkien’s Legendarium, would eventually be published, thanks to the tireless efforts of Tolkien’s youngest son, Christopher. The Silmarillion, a one-volume summary of the Legendarium, was published in 1977, followed by the twelve volumes of the History of Middle-earth (1983-1996), a collection of different versions of the texts and unpublished outlines and rough drafts. Finally, a collection of previously unpublished stories, edited by Christopher, The Children of Húrin, came out in 2007.

So the true depth and breadth of Tolkien’s stunning oeuvre has come to light only gradually, as the posthumous texts enrich and enhance his “secondary world,” granting it an exceptional consistency. The unanimously acknowledged excellence of Tolkien’s oeuvre stems from the author’s extraordinary capacity as a world-builder, and to the compelling sense of coherent completeness it creates. Following in that vein, which was essentially inaugurated by Tolkien, fantasy has established itself as the contemporary genre devoted to the discovery of imaginary worlds that readers, players and spectators are invited to explore.