Looking for C.S. Lewis

Raised in a religion that he returned to as an adult, Clive Staples Lewis left an immense body of work, brimming with worlds and bestiaries of all sorts, but profoundly tied to religion.

A Childhood Shaped by Imagination

Clive Staples Lewis (1898-1963, one of the twentieth century’s most important fantasy authors, is also known for his literary criticism and his Christian apologetics. Born in Belfast, and having lost his mother at an early age, young C. S. Lewis and his brother, Warren, sought refuge by writing about and illustrating an imaginary world they christened Boxen, which was inhabited by “anthropomorphized animals.” Lewis never lost that childhood pleasure, which later came into harmony with a Christian faith that he had found off-putting as a youth.

Through long conversations with his friend J. R.R. Tolkien, in the city of Oxford, where the two men were professors and members of the Inklings, he came to see the story of the Bible as the most magical of tales, and the mysteries of faith as the thing that requires the deepest immersion and the fullest emotional investment.

Intertwining Mythology and Religion

From then on, his fiction would be devoted to spreading the messages of Anglicanism. The adventures of Elwin Ransom, a fictional Oxford philologist, and the connecting thread in the three novels in Lewis’s “Cosmic Trilogy,” Out of the Silent Planet (1938), Perelandra (1943) and That Hideous Strength (1945), can be described as theological science fiction. They intertwine elements from space opera, Arthurian legend, and spiritual allegories. Perelandra, for example, is an aquatic paradise. Ransom manages to prevent its “Fall” by facing down his eternal adversary, Professor Weston, a scientist intent on both progress and glory who succumbs to demonic possession.

Lewis also wrote a significant body of Christian apologetics, and was able to share the comforts of faith by hosting a very popular radio program urging listeners not to lose faith during the darkest hours of World War II.

An Inspired Author of Fantasy

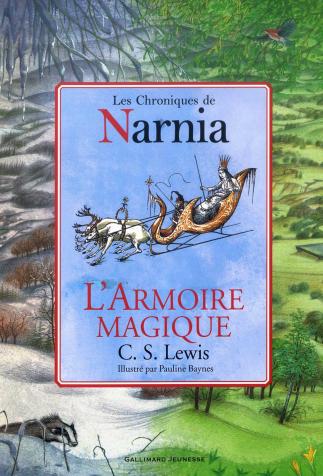

Lewis’s fantasy oeuvre is dominated by the success of his Chronicles of Narnia, seven volumes aimed at young readers that were published annually from 1950 to 1956. But his novel Till We Have Faces (1956), which transposes the myth of Cupid and Psyche to an ancient barbarian kingdom, is also worth mentioning. In it, Psyche’s older sister, the ugly Orual, vents her wrath at the gods before coming to understand the nature of their presence in all human lives.

The world of Narnia – which is accessible only to certain children, like the Pevensie siblings in the volumes that were published first – is presented as a shimmering blend of enchanting traditions. Talking animals, creatures from both mythology and folklore, diverse peoples and societies waiting for the sons of Adam and daughters of Eve to bring peace and prosperity back under the rule of the lion Aslan. The seven volumes provide a complete history of Narnia, from the world’s creation, recounted in the next-to-last volume published, The Magician’s Nephew (1955), to its Last Judgment, in The Last Battle (1956).