You Are the Hero Books: When Readers Decide the Outcome

In the 1980s, a new kind of interactive children’s book came into being: “You Are the Hero” books. Inspired by role-playing games, and often steeped in fantasy, they empowered readers by allowing them to actively influence the story.

Children’s Books

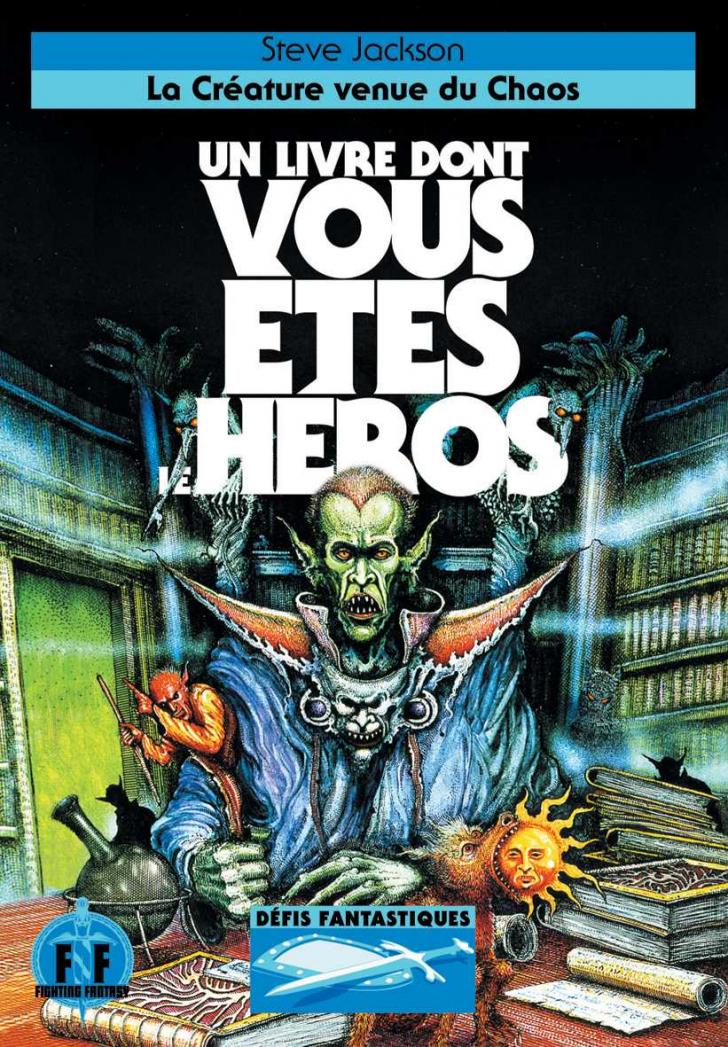

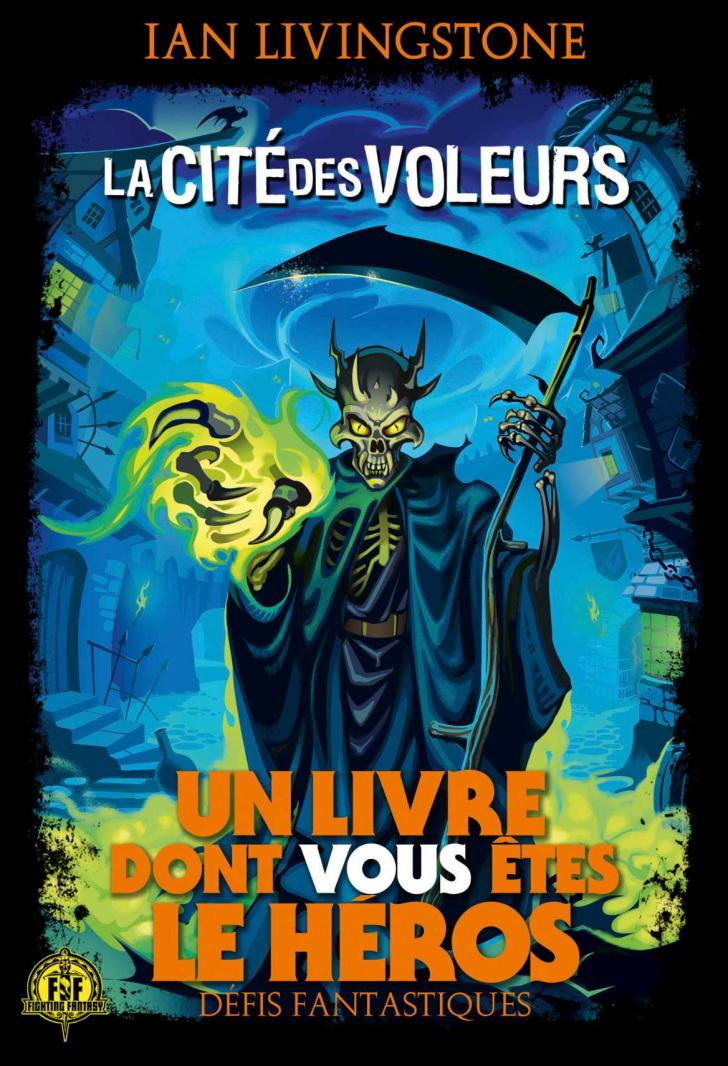

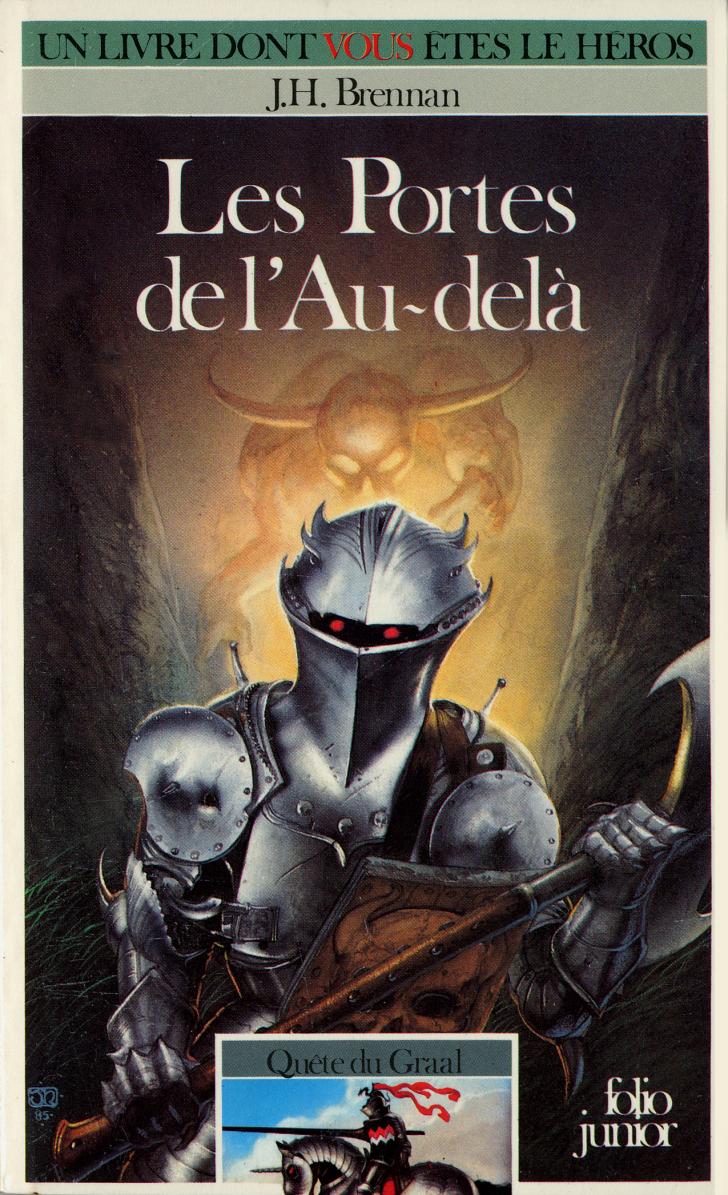

“You Are the Hero” books were profoundly similar to role-playing games. They offered reader-players a chance to interact with imaginary worlds. Their convenient paperback format, simple rules (at least compared to games like Dungeons & Dragons), and low price meant they were soon being mass-produced. Launched in the United Kingdom in 1982 by the Penguin Books as part of their children’s book collections, the first “You Are the Hero” books contributed to introducing fantasy to the general public. A similar phenomenon occurred in France, where the books were translated and published by Gallimard Jeunesse, another prestigious publisher. Their success was instantaneous. By 1983, “You Are the Hero” book sales in the U.K. had outstripped those of Roald Dahl, who was then one of the most famous and popular children’s book authors alive.

Coherent Universes

Fantasy played a key role in “You Are the Hero” books’ popularity, as is demonstrated by the title of the first (and most popular to this day) collection devoted to that new kind of book, “Fighting fantasy.” A type of fantasy, as the name implies, that focuses on the idea of a hero confronting enemies in an enclosed setting, usually a maze, which – just like in role-playing games – is called a “dungeon” to give it a medieval flair. To this day, Deathtrap Dungeon, by Ian Livingstone (1984) is still one of the best-selling titles.

The books’ success soon led to two distinct phenomena. First, the most popular titles got sequels, to build fan loyalty. So Deathtrap Dungeon was extended with two other titles. Consequently, those sequels soon lead to the creation of coherent imaginary universes (for instance, Fighting Fantasy’s Titan world was described in a stand-alone volume as early as 1986) in which both future book-games and productions in other media could take place. Fighting Fantasy video games appeared as early as 1984. So in this case, the creation of an imaginary universe obeyed both commercial and editorial strategies.

A Springboard for Illustrators

Just like pulp magazines, children’s books, role-playing games and “You Are the Hero” books count on both cover and inside illustrations often focusing on the monster, a symbol both of the fantasy world that players are about to dive into, and of the challenges they will have to face. The genre would in fact offer a number of budding fantasy illustrators a chance to express themselves and be noticed. The Fighting Fantasy collection, for example, helped lunch the career of Iain McCaig (the Deathtrap Dungeon illustrator), who would go on to become the concept artist for the Star Wars franchise. And John Howe drew the French covers for the GrailQuest series, (1985-1988).