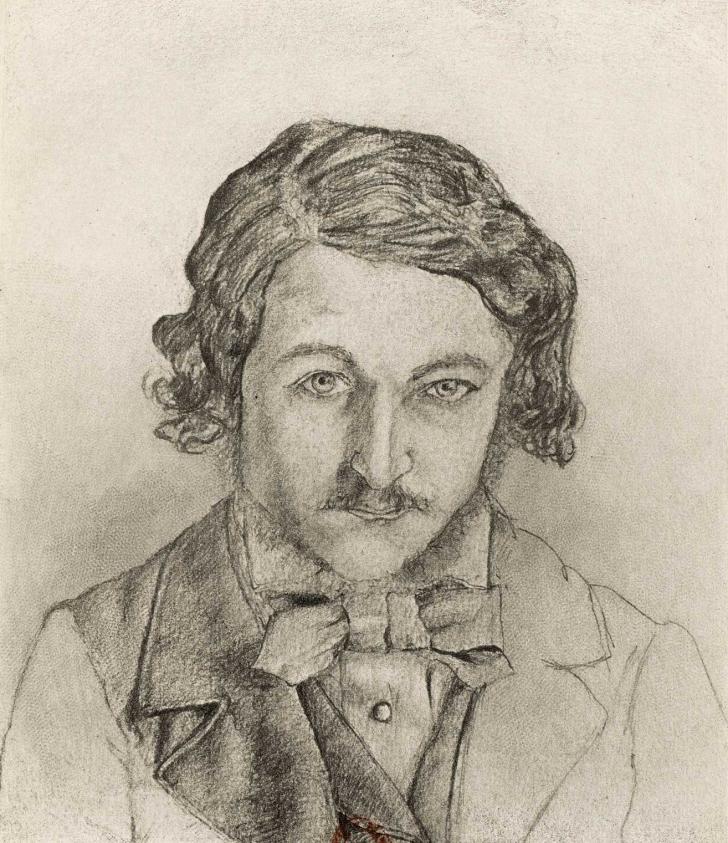

William Morris: The Writer with a Thousand Faces

History buff, defender of the down-trodden, well-known writer, design pioneer… there are many ways to describe William Morris. The writer was the first to bring prestige and cachet to fantasy.

A Protean Artist

William Morris (1834-1896), at the crossroads of various movements that contributed to the genre’s emergence, was the person responsible for bringing fantasy to England. In addition to his work in the visual arts, he also distinguished himself as a translator, printer, militant political reformer… and author of the earliest fantasy novels.

Design Pioneer

Although he had many interests, their connecting theme was a fascination with the marvels of the past, particularly the Middle Ages. A multi-talented artist, Morris is best remembered nowadays as a member of the pre-Raphaelite group and particularly as the most celebrated designer in the Arts and Crafts Movement. His objective was to revive craftsmanship and produce beautiful, relatively affordable items so that the alliance of esthetics and usefulness would elevate both craftsmen and consumers by providing the satisfaction of a job well done.

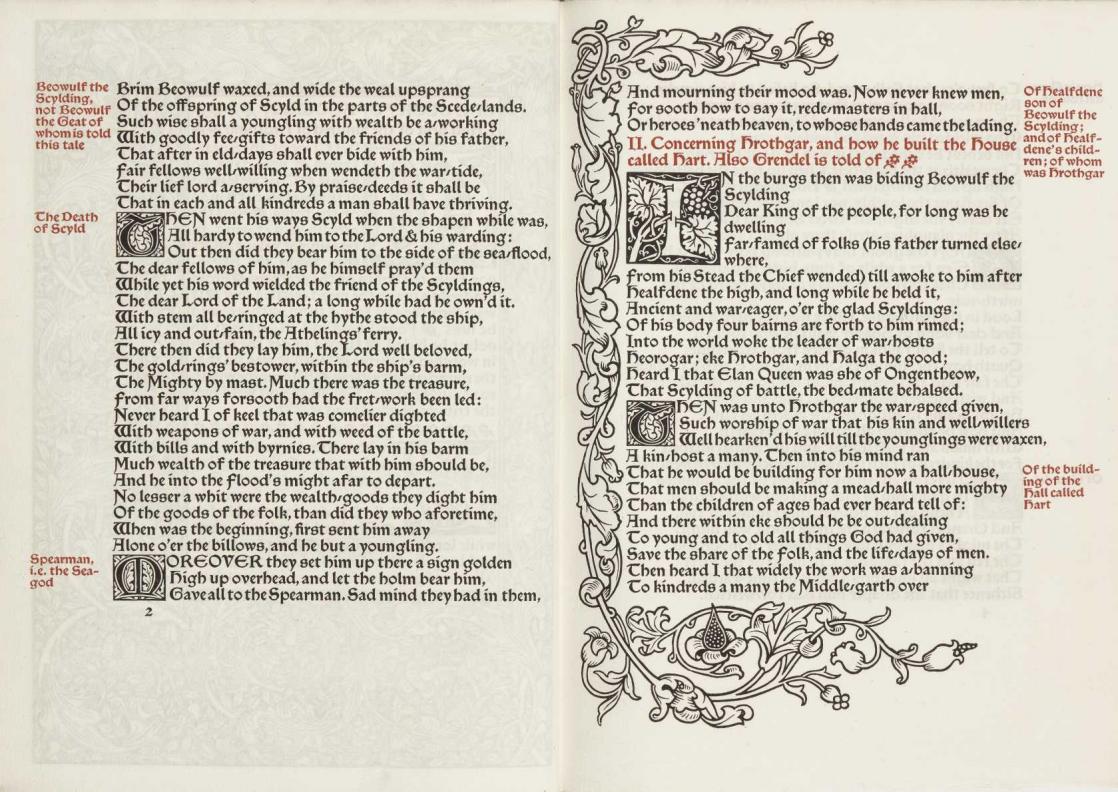

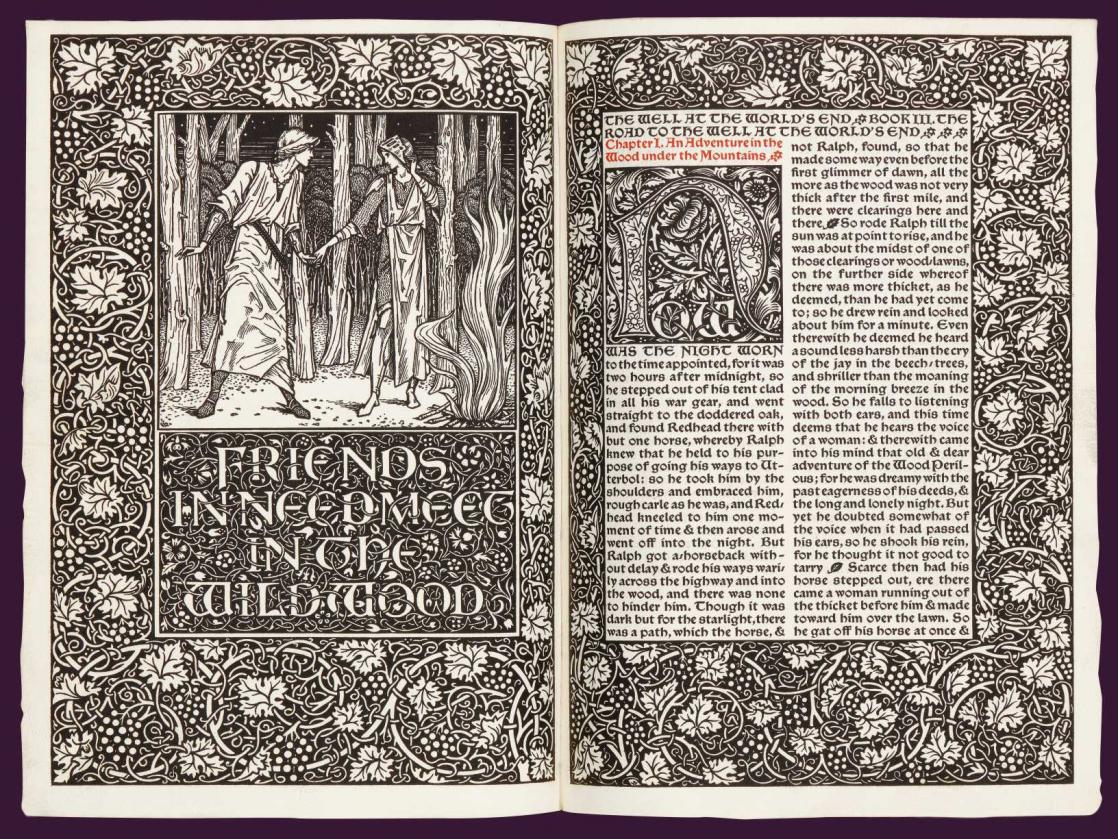

Architecture, furniture and decoration all needed to match in that ideal. He implemented it in his own “Red House,” which he built and lived in from 1859 to 1865. Morris even set up a print shop in order to reinvent the techniques and typographies of medieval manuscripts for the industrial age. From 1891 to 1898, 54 books were published by the author’s own publishing house, Kelmscott Press, including 17 of his own and a celebrated edition of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (late fifteenth century), illustrated by the renowned pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones.

Translator, Poet and…

In his time, William Morris acted as a kind of cultural ambassador, promoting the preservation of cultural heritage and the (re)discovery of England’s own epic and mythical traditions. He translated, adapted or rewrote many of fantasy’s founding texts: from ancient Greek and Roman epic poems, like his translations of Virgil’s Aeneid, in 1875-1876 and Homer’s Odyssey, in 1887-1888; to the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf (in 1895, with A. J. Wyatt), French medieval romances (Old French Romances, 1896) and, most significantly, Northern traditions, which he was instrumental in popularizing, thanks to his collaboration with the Icelandic scholar Eiríkr Magnússon.

They co-signed a deliberately archaic-sounding translation of the Völsunga Saga (1870), before Morris proposed a vast rewriting in epic, or dactylic, hexameter: The Story of Sigurd the Volsung and The Fall of the Niblungs (1876). Lastly, as a fervent fan of the Arthurian legend, he entered into a dialogue with Queen Victoria’s Poet Laureate, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, author of the twelve-volume poem cycle Idylls of the King (1859-1885). In his The Defence of Guenevere (1858), Morris gave Arthur’s queen a chance to defend herself against the moral conservatism that condemned her.

… Libertarian Activist

William Morris’s Middle Ages conform to his leftist political ideals. The author portrays the era as one of brotherhood and kindness to the marginalized, women, and proletarians, whom he always defended with great conviction. His personal life was considered scandalous – he lived in Kelmscott Manor with both his wife, Jane Burden, and his close friend, the turbulent Dante Gabriel Rossetti, her lover; his protagonists were sometimes female, like Birdalone, whose adventures are recounted in The Water of the Wondrous Iles (1897, posthumous).

In 1885, Morris co-founded the Socialist League, for which he was both a financial benefactor and tireless spokesperson. He then devoted much of the last years of his hyper-active life to social struggle alongside the most destitute. In his fiction, he always proposed alternative social models. His stories ranged from historical-fantasy novels like The House of the Wolfings (1889), which extolled the Norsemen’s nobility in defending themselves against the Roman invaders, to futuristic utopian-socialist tales like News from Nowhere (1890) and the fantasy texts that occupied his final years. Not only did Morris do his best to change his own world, he also dreamt of a Golden Age, and advocated for replacing capitalist domination and industrial disfigurement with a pastoral, communitarian and morally libertarian ideal.

Finally, Morris was one of the first to describe – in books written for adults in a deliberately archaic style – imaginary worlds in which the supernatural is one of the defining features: in other words, fantasy novels. Those initiatory tales –including The Story of the Glittering Plain (1890), The Sundering Flood (1897, the only one with a map on the cover), and especially The Wood beyond the World (1894), The Well at the World’s End (1896) and The Water of the Wondrous Iles (1897) - were very novel and exotic for his contemporaries.