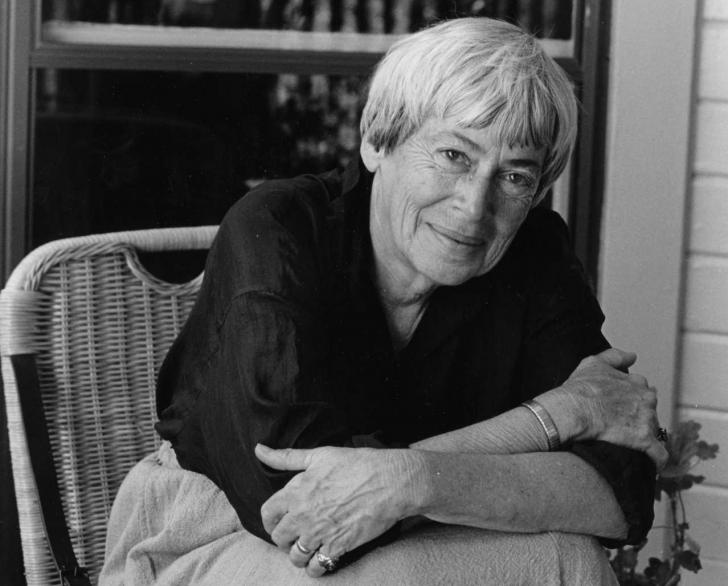

Ursula K. Le Guin: A Woman at the Peak of Fantasy

Now recognized as a major figure in the genre, Ursula K. Le Guin wrote a huge number of stories. Among them, the Earthsea Cycle is considered to be one of fantasy’s masterpieces.

Ursula K. Le Guin and the “Relationship to the Other”

When she passed away in January 2018, the American author Ursula K. Le Guin left an important literary oeuvre that has continued to accrue fame and recognition since her death. The daughter of two anthropologists, Le Guin was both rigorous and erudite. Her work focused on the ethical and spiritual aspects of alterity and of taking the perspective of the “Other” into account. Her first major work, the The Hainish Cycle (from 1966), was categorized as science fiction. Exploring a different planet in each volume, it offered reflections on the relationship between the colonizers and the indigenous populations they encountered (in Planet of Exile, 1966, and The Word for World Is Forest, 1972, which is often seen as a metaphor for the Vietnam War).

Her heroes are ethnologists or diplomats, like in Rocannon’s World (1966) and The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), a tale in which a male native of Terra (Earth) winds up in a world where the distinction between men and woman is meaningless. At the other end of her long career, her last novel, Lavinia (2008), provides a retelling of the Aeneid (Virgil, 29-19 B.C.E.) from the point of view of the eponymous heroine, the Latin princess whom Aeneas marries at the end of his journey. The author thus offered a reflection on how history is written.

A Multi-Faceted Writer

In addition to writing numerous novels, Ursula K. Le Guin expressed style as a poet, a translator (most notably of the Argentinean author Angélica Gorodischer, for the superb Kalpa Imperial, 2001), and an author of short stories, novellas and critical essays that were collected in The Language of the Night (1979).

She also created a form of fictional anthropology in Always Coming Home (1985), presented as an anthropological case study composed exclusively of documents describing rituals, myths, biographies, poetry and chants gathered by anthropologists from the distant future about the Kesh people.

She wrote for children, too, with the Catwings book series, started in 1988 (about charming animals who incarnate another form of alterity, winged cats who have trouble fitting in), and the Annals of the Western Shore trilogy (2004-2007), an intimist portrayal of three journeys towards emancipation.

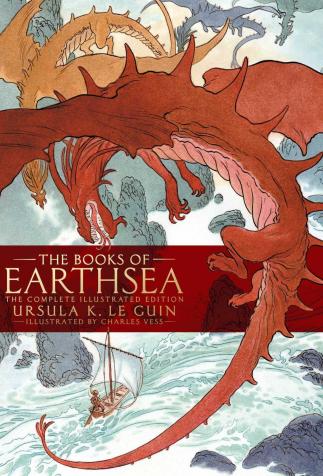

The Earthsea Cycle: A Monumental Work

Still, Ursula K. Le Guin’s greatest contribution to fantasy remains her Earthsea Cylce (1964-2001), part of which was adapted to the screen by Goro Miyazaki in 2006. With a first short story in 1964 and a novel in 1968, the cycle was begun while Tolkien’s style was ascendant in the fantasy genre. Nonetheless, Le Guin tried to distance herself from it.

All five novels take place in an archipelago world inhabited by dark-skinned humans and by dragons. It is a world where magic is bound to extreme mastery of language (to know things’ or beings’ “true name” grants power over their essential nature). The main character in the first trilogy (1968-1972), Ged, is a gifted young wizard who eventually becomes the archmage of the wizardry school on the island of Roke.

Published in 1990, Tehanu, the fourth volume, follows Le Guin’s own evolution, as she becomes more interested in the stories of the female characters. The book reprises the story of Tenar, who was saved by Ged in The Tombs of Atuan (1970), the second volume of the cycle. Tehanu continues Tenar’s story, describing how she would go on to save an abused little girl, who turns out to be related to the dragons.

Finally, Tales of Earthsea (2001) is a collection of short stories, some of which – like “The Finder” (2001), about the founding of the school on Roke – are set in the distant past. Others, like “Dragonfly” (1997), in which readers find out how the heroine challenged the ban on women studying magic, take some of the author’s reflections further.

The subtle intelligence of Le Guin’s texts combined with her humanist themes, harbingers of contemporary ecological and feminist issues, have placed Ursula K. Le Guin squarely in the top tier of fantasy’s pantheon.