Populating Magical Worlds

Once a fantasy world’s history and geography have been invented, its regions can then be inhabited. Dwarves, humans, elves and trolls often co-exist in those worlds, whether peacefully or conflictually.

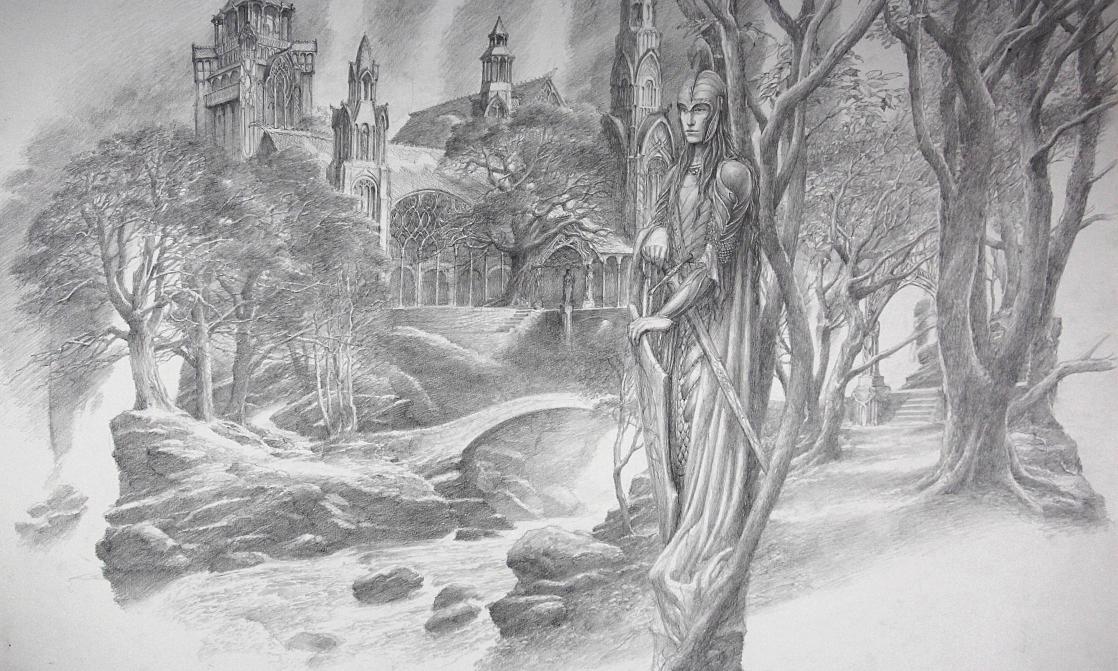

Elves are undoubtedly fantasy’s most emblematic characters. While folklore turned them into the kindly or slightly threatening representatives of the little people, Tolkien (The Hobbit, 1937, The Lord of the Rings, 1954-55) restored elves’ mythological origins. In his own oeuvre as well as in the high fantasy it has inspired, they are handsome, noble creatures, deeply tied to nature and spirituality. The elves in Glorantha, Greg Stafford’s game-world (since 1966) are actually plant-men. Called Sithis in Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn (Tad Williams, since 1988), and Lios alfar in The Fionavar Tapestry (Guy Gavriel Kay, since 1984), they are always an extremely ancient race that is gradually dying out along with the magic and songs or chants they are the guardians of. That motif is present elsewhere, too, including in Christopher Paolini’s Inheritance (since 2003). On the other hand, the “dark elf” version sprang up early on to enliven role-playing games.

Elves and Dwarves: Two Opposing Worlds

Elves are frequently opposed to or paired with another primordial race, dwarves, like Legolas and Gimli in Tolkien’s oeuvre, and Tanis Half-Elven and Flint Fireforge in the Dragonlance series (Weis and Hickman, since 1984). While the former have ties with the forest, the latter emanate from mountains and caverns, and are associated with minerals and blacksmithing. They are generally sturdy but rough, sometimes boorish, and often jolly.

A Wide Range of Races

Alongside those indispensable elements of high or epic fantasy, are many other recurrent figures. Giants are linked to the origins of the world; the rare specimens who subsist keep their distance from humans (in both George R.R. Martin and J. K. Rowling). Tree-men, like Tolkien’s Ents, are guardians of the old magic who are opposed to technology, like the forest spirits in Princess Mononoke (Hayao Miyazaki, 1997). Shape-shifters, like Beorn in The Hobbit or the wargs in A Song of Ice and Fire, possess totemic powers.

Some worlds, particularly in children’s fantasy, have a multitude of races, as well as animal creatures, without there being a clear line distinguishing the two. Centaurs are both wise and wild in J. K. Rowling and C. S. Lewis; animals can talk in The Chronicles of Narnia (since 1950), and dragons can be glib manipulators (in The Hobbit) or telepathic companions (Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern, since 1967). Fantasy’s overarching message almost always promotes tolerance and the advantages of diversity.

Human Societies

Humans – including magicians, who are sometimes a separate race (Tolkien) or a category of the population endowed with extra powers (Rowling) – are nevertheless omnipresent in fantasy, in order to facilitate readers’ sense of identification. Among other characters, the usually young heroes and heroines, will often discover the complexity of the world around them along with readers. character archetypes have become established, especially for the needs of games: paladin, magus, wizard, explorer, thief, and more.

Different geographical zones have also become associated with specific races, which echo and agglomerate historical character traits or imagined geographies. These include the Riders of Rohan in Tolkien, and in A Song of Ice and Fire, the fiercely loyal Norsemen, and a people from Dorne, in the desolate far south, who have been molded by the desert. G.R.R. Martin takes categorization to the “house” level, with each one being endowed with its own coat-of-arms and motto.

Recurrent Monsters

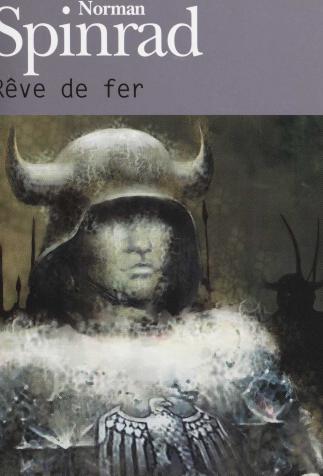

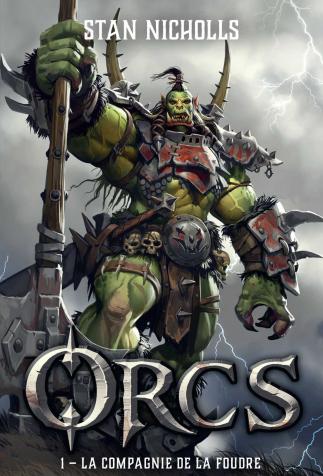

While enemies may be recruited amongst humans, fantasy has arguably overdone the notion of enemy races, like trolls, goblins and orcs. For years, their problematic status and fundamentally bad nature justified massacring them. But a certain critical distancing soon emerged. In The Iron Dream (since 1972), Norman Spinrad has been bluntly revealing the fascism inherent in constructions like that by conjuring up an alternative Hitler who has become a fantasy writer.

Nowadays, a greater awareness of previously unacknowledged post-colonial mindsets has imposed greater systemic subtlety. William Blanc has shown how the evolution of portrayals of orcs corresponds to those of racial minorities, figures of alterity in eras perceived as monstrous and threatening. British author Stan Nicholls’ Orcs trilogy (1999-2000) marked a turning point by recounting the story from the “bad guys” perspective, without whitewashing things.