Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings

Adapting Tolkien’s iconic work was no small feat. Since 2001, we have been able to see how Peter Jackson rose to the challenge, making the most out of both New Zealand’s majestic landscapes and recent motion-capture technology for animation.

A Successful Adaptation

At first, fans of the book were thrilled at the attention being paid to their beloved author. Tolkien had sold the audiovisual rights to his oeuvre to United Artist back in 1969, but none of the previous attempts to adapt The Lord of the Rings to the big screen – from the unrealized project involving the Beatles to Ralph Bakshi’s animated version that ended in 1978 after a single episode – had come to fruition. They were hamstrung by a lack of technology for bringing Middle-earth to life and by the obvious difficulty in summarizing a novel as vast as Tolkien’s.

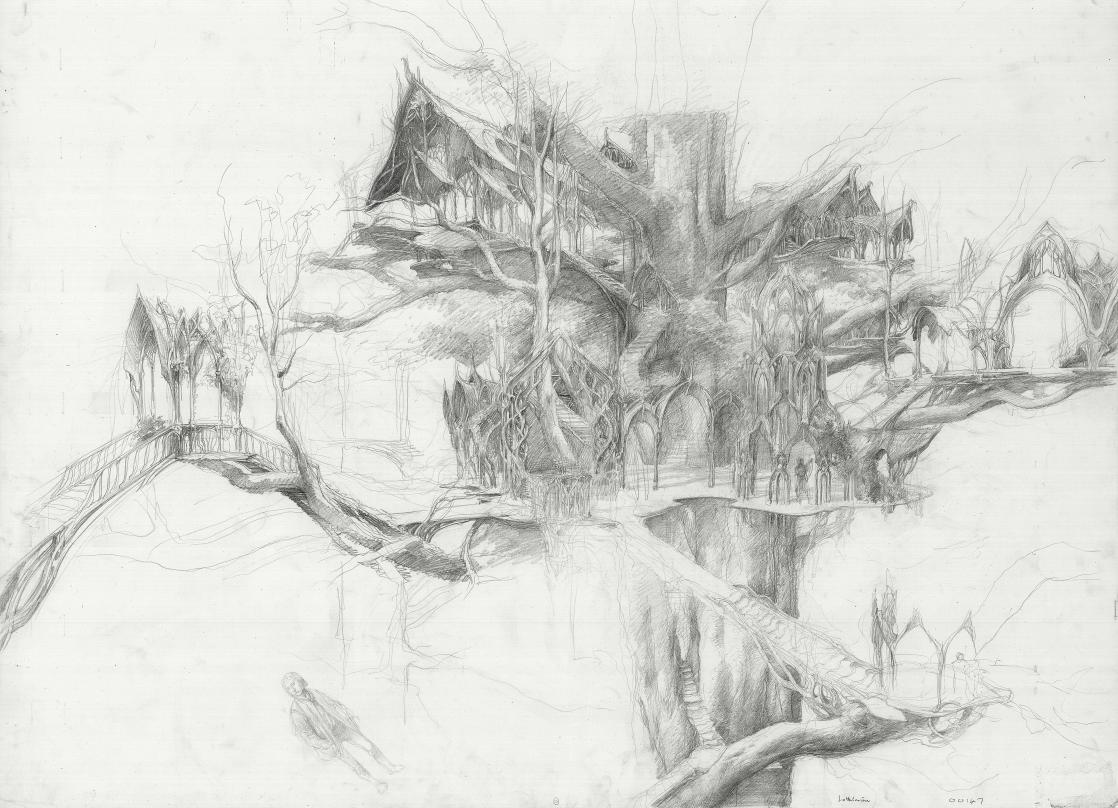

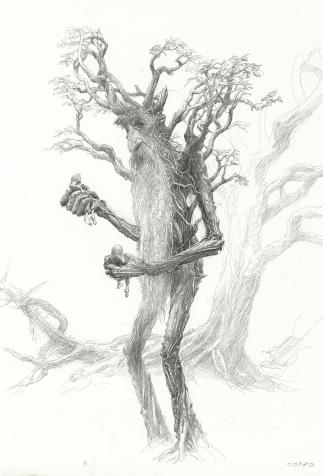

Peter Jackson made sure he would be able to make three feature-length films. Then, in collaboration with Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens, he wrote a script that hewed fairly closely to the book. Tom Bombadil was set aside, and Arwen, who was relegated to the annexes in Tolkien, was considerably developed. Although he is the co-founder of Weta Digital, a special-effects company, Jackson chose to shoot in the well-preserved landscapes of his native New Zealand. That way, he could pair technological excellence (Gollum’s motion-capture animation) with real-life effects. He wisely hired Alan Lee and John Howe – the most talented Tolkien illustrators of their generation – as chief conceptual designers, transcribing their visions of the Shire, Rivendell, and Moria in memorable scenes.

Pros and Cons

Still, Jackson's Lord of the Rings remains just one possible interpretation, among many others, of the saga. It enshrined Tolkien’s oeuvre for posterity — action-packed, aimed at young adult audiences, shaped by comic book images and role-playing figurines.

While the films did bring Tolkien’s world into a new dimension, they also deformed along the way. A lot of moviegoers now think they know The Lord of the Rings without having read the book. Some admit to having been surprised or even disappointed when they gave it a try. They came up against a challenging book that is longer and more contemplative than the films, with a noble, descriptive style. Of course, the treatment dealt out to The Hobbit (2012-2014) didn’t resolve anything: its long-delayed adaptation into a trilogy took more liberties and is far more questionable. Nevertheless, it can not be denied that there are now several different ways to approach Middle-Earth – through the written work alone, or via the broader universe inspired by the movies.