Fantasy Around the World

Although it is largely dominated by English-language production, fantasy literature has also carved out an honorable place for itself in many European countries, and has spread to other continents as well.

A Purely English-Language Phenomenon?

Born in England and having expanded in tandem on both sides of the Atlantic before turning into a pop-culture phenomenon in the United States, fantasy is undeniably an English-language genre. Even today, the translation market skews massively in one direction, and fantasy’s current success bears witness to a globalization of the imagination that is largely dominated by America, the cultural superpower.

Nevertheless, since the 1970s, when Tolkien translations became generalized and role-playing games conquered teenagers around Europe, local fantasy began to emerge in many different European languages.

La fantasy à travers l’Europe

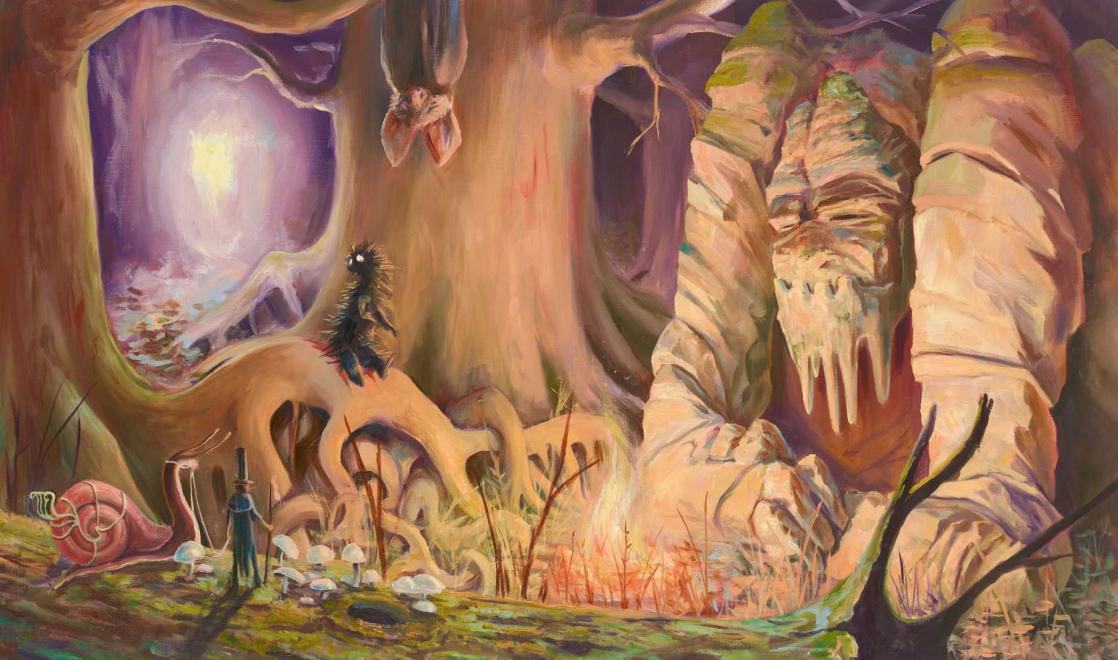

German fantasy, which has a welcoming cultural context thanks to Romanticism and the Brothers Grimm, is the perfect example of that. Ever since Michael Ende and his international bestseller, The Neverending Story (1979), the well has never run dry, and more and more authors have been achieving success. Among them are Wolfgang Hohlbein, who is extraordinarily popular in Germany (Märchenmond (Magic Moon) in 1982); Die Chronik der Unsterblichen (Chronicles of the Immortals), since 1999); Cornelia Funke, a well-known YA author (the Inkheart trilogy, since 2003); Kai Meyer, who has, among other books, revisited traditional Germanic legends (Loreley, 1998 and Nibelungengold, 2001); and Walter Moers, creator of the continent of Zamonia (with the City of Dreaming Books) and his 13½ Lives of Captain Blue Bear, whose hero has been the star of a children’s cartoon series (since 1993), two novels, a film (1999), a stage musical (2006) and more.

International acclaim for any given language region is often limited to a single star author. That is the case, for example, with Andrzej Sapkowski and his Witcher (since 1986, adapted as a video game since 2007 and a TV series since 2019), who are icons in Poland; and with the Spanish author Javier Negrete and his Tramorea saga (since 2003). But that doesn’t mean that those authors are all those countries have to offer, as can be seen by the vibrancy of French fantasy, for example.

An Intercontinental Genre

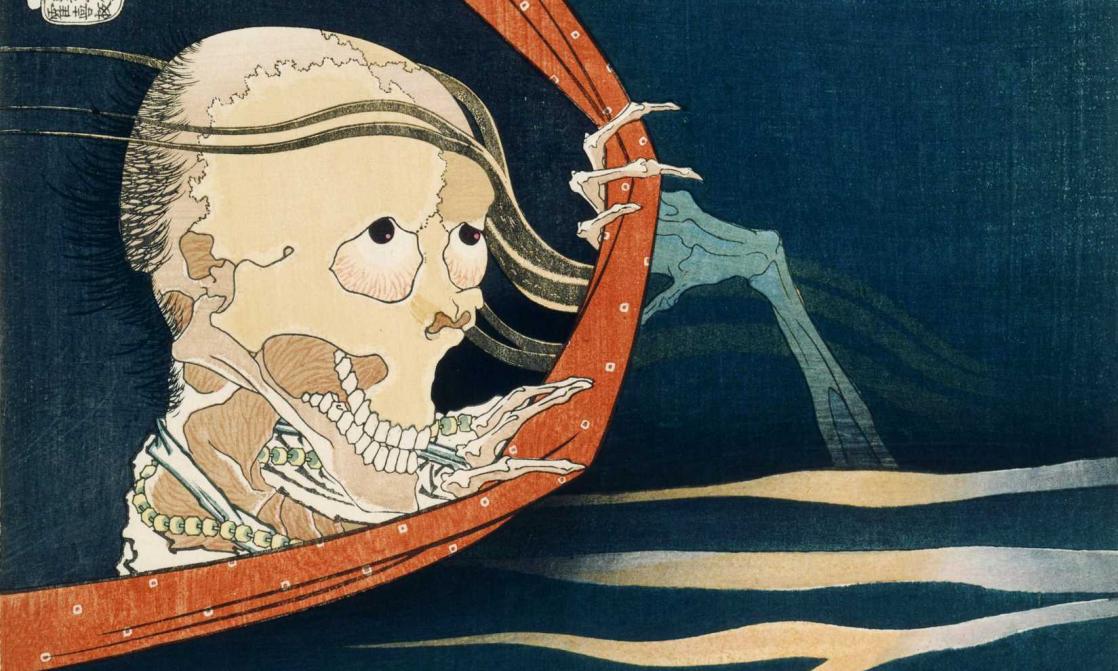

It can be extremely interesting to interweave the enchantment of fantasy literature with supernatural traditions that are specific to given cultural regions, such as the Hindu pantheon, Chinese ghost stories, Japanese animist Kami and Yōkai, and African and Afro-Caribbean witchcraft.

South America, for example, has a rich cultural tradition that is frequently associated with the fantastic, like the short stories by Argentinean authors Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares, starting in 1940, or the magical realism of the Cuban author Alejo Carpentier (Explosion in a Cathedral, 1962), the Colombian Gabriel Garcia Márquez (One Hundred Years of Solitude, 1967) and the Mexican Carlos Fuentes (Terra nostra, 1975).

Similarly, in Africa, The Famished Road (1991) by the Nigerian author Ben Okri, is seen as being part of the “legitimate” school, on the cusp of literary rather than genre fiction. But a new generation of African writers, dominated by women writing in English (Nnedi Okorakor, Nisi Shaw, Lauren Beukes and others), has made the fantasy genre its own.

Until quite recently, it seemed more respectful towards those forms coming from “differentiated” cultures not to assimilate them to a modern, English-dominant genre. But digital media and economic globalization having torn down many borders, we are now witnessing deliberate combinations of supernatural traditions, like the Japanese manga Full Metal Alchemist (Arakawa Hiromu, 2001-2010) and Witch Hat Atelier (Shirahama Kamome, since 2018), and the Sino-American film The Great Wall (Zhang Yimou, 2016).