Victorian England: Birthplace of Fantasy

As the first country to undergo massive industrialization, England was also the first to endure the economic and social upheaval that followed. The earliest fantasy was born in response to those radical changes.

Although it draws inspiration from older magical tales, myths, legends and epic poems, fantasy as its own specific genre emerged in late-nineteenth-century England, during the Victorian (1837-1901) and Edwardian (1901-1910) eras. Its birth and growth accompanied historic upheaval that was at once social, economic and existential, and that profoundly affected mentalities as well as lifestyles. England, with its vast colonial empire, was the world’s largest economic power, and it experienced brutal industrialization. In that culturally rich context, a handful of writers chose to focus on the supernatural and to seek refuge in enchanted worlds: thus was modern fantasy born.

A Response to Realism

With its naturalist aspect, realism, the literary movement one generally associates with the nineteenth century, seems to be diametrically opposed to the reign of the imagination. Its best-known figures were Dickens in England, Balzac and Zola in France, and Stephen Crane in the United States. The role it assigned to literature was to represent reality, even at its crudest. Yet the simultaneity of fantasy and realism is no coincidence. In order for the “speculative” or “imaginative” genres (including both fantasy and science fiction) to be able to emerge and develop their portrayals of the irrational and the supernatural, the categories “reason,” “nature,” and “science,” had to be sufficiently well-anchored in people’s minds.

What’s more, whereas realism went hand in hand with urban, industrial and rationalist development, choosing an imaginary world could be seen as a form of resistance to modernity. Particularly in England, a range of diverse but convergent attempts to preserve a form of enchantment, a bit of magical irrationality in people’s relationship to the world can be observed. That was the fertile ground from which fantasy would spring.

Rediscovering the Medieval Past

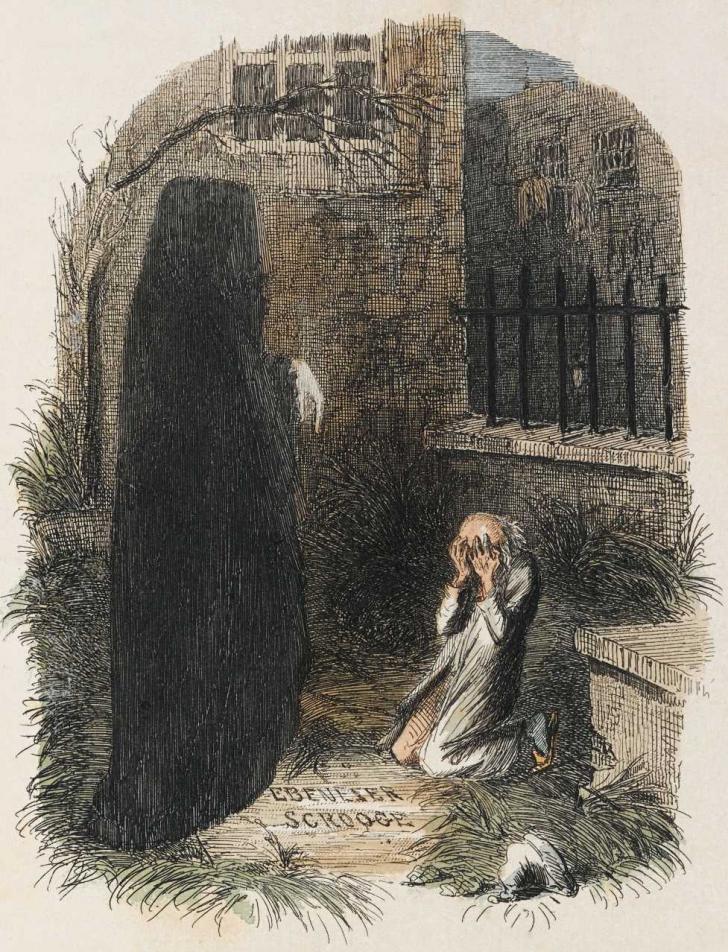

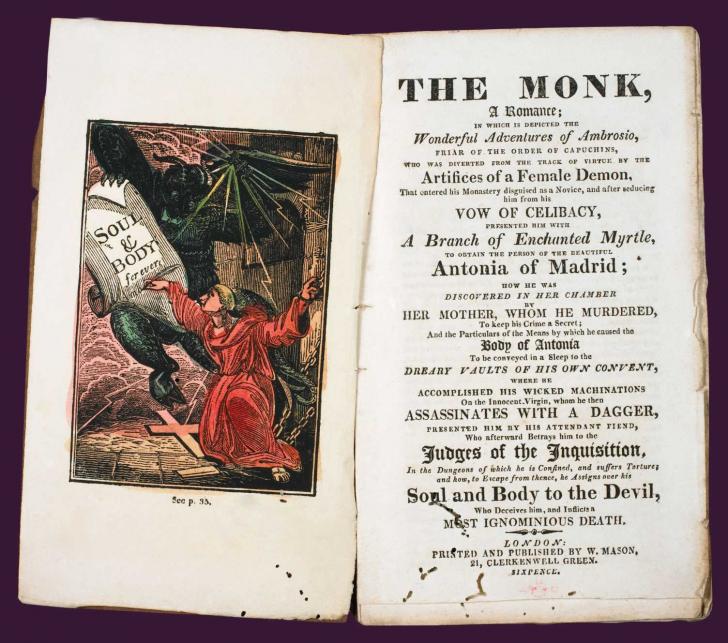

For one thing, England already enjoyed a rich tradition of imaginative literature, notably with the significance of the Gothic movement in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries. With his Castle of Otranto (1764), Horace Walpole was the pioneer of that genre; it was followed by M. G. Lewis’s The Monk (1796) and Ann Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho (1794). In Northanger Abbey (published posthumously, 1817), Jane Austen poked fun at that wildly popular literary trend. Her heroine reads too many best-sellers of her time, which leads her to project Gothic terrors (haunted castles and devilish pacts) onto an era that was meant to be one of enlightenment and progress for civilization. Major works in the genre would continue to be written in English throughout the nineteenth century, from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) to Oscar Wilde’s Portrait of Dorian Gray (1890) and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897).

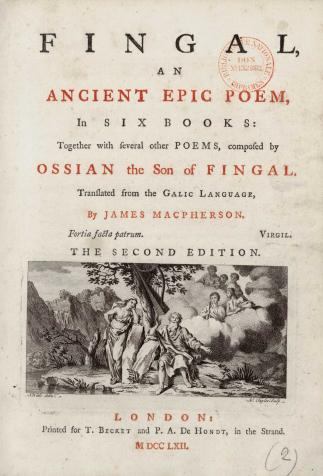

The renewed interest in folklore provided another wellspring of inspiration, one that distanced itself from the representation of alterity as threatening or distressing. Those folklore traditions had a strong presence in the faery of children’s literature, which was then experiencing a “golden age,” but were not limited to it. Folklore also contributed greatly to another major eighteenth-century English-language literary phenomenon, the “Celtic revival.” That movement was launched by the 1760 to 1765 publication of a series of “Gaelic” poems attributed to a bard of the Dark Ages called Ossian… They were actually the work of a Scottish poet named James McPherson, who presented himself as their translator. By the late nineteenth century, another Scot, the folklorist Andrew Lang, had published his collection of Fairy Books of Many Colours. Although J.R.R Tolkien, who was born in 1892, would not share Lang’s attitude towards fairy tales, myths and legends, that collection was nonetheless his introduction to those traditional tales.

Back to the Roots

Renewed interest in the Middle Ages, a little-studied and generally disdained era that was “rediscovered” in the late-eighteenth/early-nineteenth century, was another element of the search for national origins. It also indulged a desire for escapism – not to another place, but to the same place in another, bygone era. Walter Scott’s highly influential early-nineteenth century oeuvre offers one of the first examples. Having edited a medieval tale of Tristan, Sir Tristrem, early in his career (1804), as well as writing the book-length narrative poem “The Lady of the Lake” (1810), he was considered the father of the historical novel, a genre that would be epitomized in France by Alexandre Dumas and Victor Hugo. Walter Scott’s swashbuckling heroes went by the names of Ivanhoe (1819), who lived in the time of Richard the Lionheart and Prince John, and Quentin Durward (1823), who fought in France during the reign of Louis XI.

As a very successful author, he was able to have a striking mansion built in the medievalist style of his time. Gothic Revival was a popular medievalist aesthetic, particularly in architecture. Theorized by John Ruskin in England, it was also implemented by Viollet-le-Duc in France. Proust, for example, shared the movement’s fascination for cathedrals. Lastly, the “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood,” a group of artists led by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, declared in their name itself their goal of going back to a style from before the Renaissance, symbolized by the great master Raphael, to lay the foundations of a renewed sense of community.

The New Romanticism

The revival of “romances,” a term which was used as opposed to “novel” to designate adventure-filled, fanciful stories in the Romantic style – which for some included even medieval literature – was the last incarnation of the anti-modernist, anti-realist movements. This time, “elsewhere” came in the shape of the far-away lands and little-known cultures the colonial empires had introduced to Europeans. Robert Louis Stevenson, a well-travelled writer and the celebrated author of both Treasure Island (1883) and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde (1886), is an excellent example of that movement, as well as one of its theoreticians.

In H. Rider Haggard’s oeuvre (most notably King Solomon’s Mines, 1885; She and Allan Quatermain, 1887), exoticism is in constant contact with the supernatural, and African expeditions are a pretext to explore primitive modes of thought and lost civilizations. The adventure novel and fantasy genres were very similar, often overlapping, at that time. The same thing would also be true in the United States, with E.R. Burroughs and Robert Howard.

Fantasy’s Pioneers

William Morris, a fascinatingly multi-facetted artist, is the figurehead of a loose network of authors from both his own generation and later ones who contributed to gradually defining the genre. The pastor and theologian George MacDonald is one of his most notable predecessors. MacDonald produced a major and ground-breaking oeuvre, some of which was intended for children (The Princess and the Goblin, 1872) but much of it for adults, particularly the allegorical quest Phantastes: A Fairie Romance for Men and Women (1858), and Lilith: A Romance (1895). Both Lewis Carroll, whom he mentored, and C.S. Lewis, on whom Phantastes had made a huge impression, owe a great debt to MacDonald.

Charles Kingsley, who wrote the allegorical tale The Water-Babies (1863), is also worth mentioning, as is George Meredith, a renowned author of Victorian romances. He started his career with a humorous oriental fantasy, The Shaving of Shagpat: An Arabian Entertainment (1856).

At the turn of the century, bridging the pioneers and the Tolkien-Lewis post-war generation, Lord Dunsany wrote numerous tales composing a fragmentary cosmogony, starting with The Gods of Pegāna (1905), and the novella The King of Elfland’s Daughter (1924). Eric Rücker Eddison was also very popular in his day, with his shimmering world Zimiamvia, the stage for noble struggles between Witchland and Demonland (The Worm Ouroboros, 1922). And we mustn’t forget Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who also wrote both fantasy adventures like The Lost World (1912) and a 1922 book, The Coming of the Fairies, based on an article of his defending the authenticity of the “Cottingley Fairies” photographs.

By the early twentieth century, most of the major trends that fantasy would follow had been established: the dual influence of fairy tales and myths; inspiration from ancient cultural traditions; writing styles ranging from texts intended for children to the most elevated tone; but always creatures, heroes and worlds who impose their strong thematic coherence on any definition of the genre.