Travel to Long Ago and Far Away

Fantasy’s imaginary worlds are often inspired by the Middle Ages, or other bygone eras. To fire readers’ imagination even more, or to critique the modern world, authors often transport us to a fantasized past.

Out of all the historical periods, the Middle Ages seems to be the one we associate with fantasy most instinctively. Some of the genre’s most iconic authors were also scholars with in-depth knowledge of medieval texts. Before he wrote The Hobbit (1937) or The Lord of the Rings (1954-1955), J.R.R. Tolkien published an annotated edition of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, a fourteenth-century text, and translated Beowulf, two classics of medieval Anglo-Saxon literature. But the bond between fantasy and the Middle Ages is also based on the fact that ever since the late eighteenth century, that period has been seen as the antithesis of modern society. A horrifying antithesis for some; but a marvelously appealing one for those who are less convinced of the advantages of the changes wrought by the Industrial Revolution.

Fantasized Middle Ages

The Middle Ages, and, by extension, the Celtic worlds, became objects of fascination and, therefore, the subjects of both novels (most notably Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe, in 1819) and artwork (particularly by the pre-Raphaelites). Even architecture adopted neo-Gothic aspects. In that broad trend, historically accurate rediscovery of the era soon yielded to to a fantasized dreamscape. From that time until now, the Middle Ages have been more fantasized than studied.

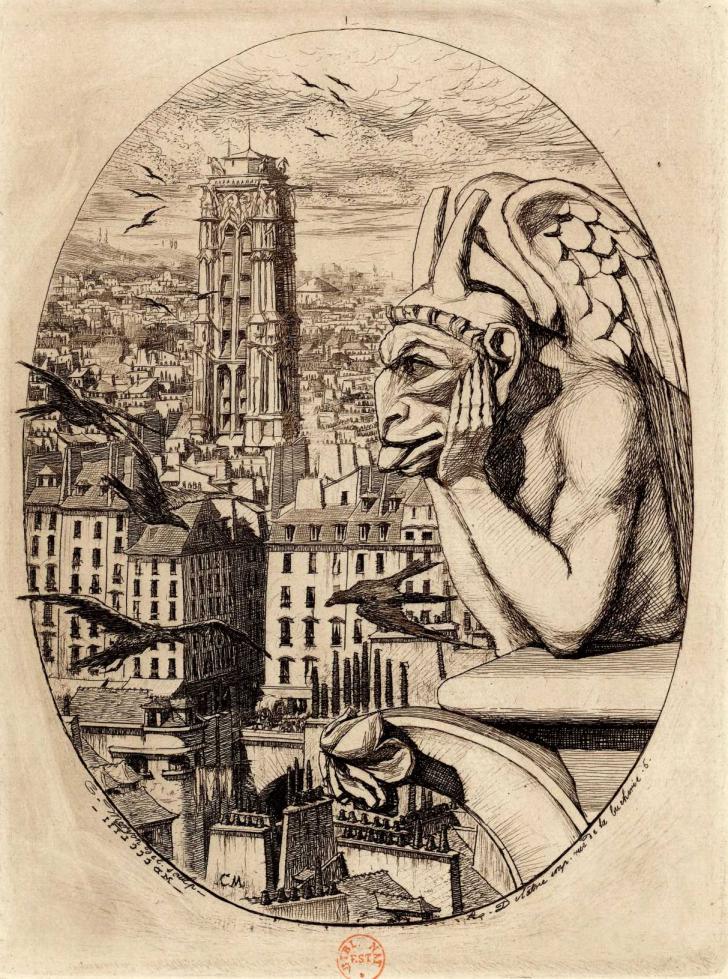

In the mid-nineteenth century, the architect Viollet-le-Duc posed chimera on the balustrade of the western façade of Notre Dame cathedral – chimera that didn’t exist in feudal times – in order to create an image of a phantasmagorical era brimming over with magical marvels.

Fantasy obeys a similar logic. The point is not to write an accurate historical account, but to compose an imaginary tale based on elements associated in the popular imagination –albeit sometimes wrongly– with the feudal era. Over the course of two centuries, as fears about modernity and its excesses have grown, the fantasized Middle Ages, the “medievalism” that fantasy is undoubtedly the most accomplished expression of, has overtaken the actual Middle Ages in the field of culture. There are far more medievalist fantasies being produced for the large or small screen than historical films or series.

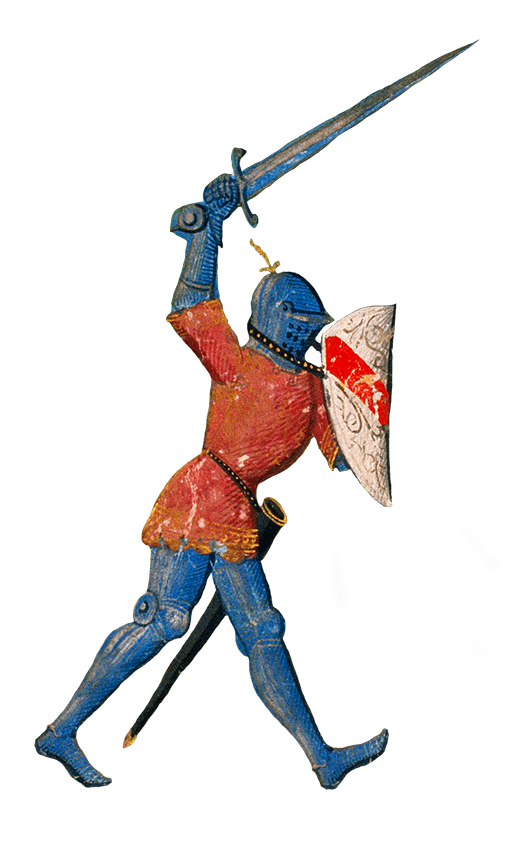

So fantasy’s Middle Ages are made up of a series of stereotypes born of the medievalist imagination to signal that we are now in a long ago that we have become familiar with over the past two centuries. It is actually a totally familiar alterity, a far-away that is comfortably close to hand, thanks to the massive use of iconic themes: castles, knights, ladies, princesses, witches, and nowadays, wondrous nd magical people and creatures (dragons, elves, dwarves and orcs).

The Fantasy of Elsewhere

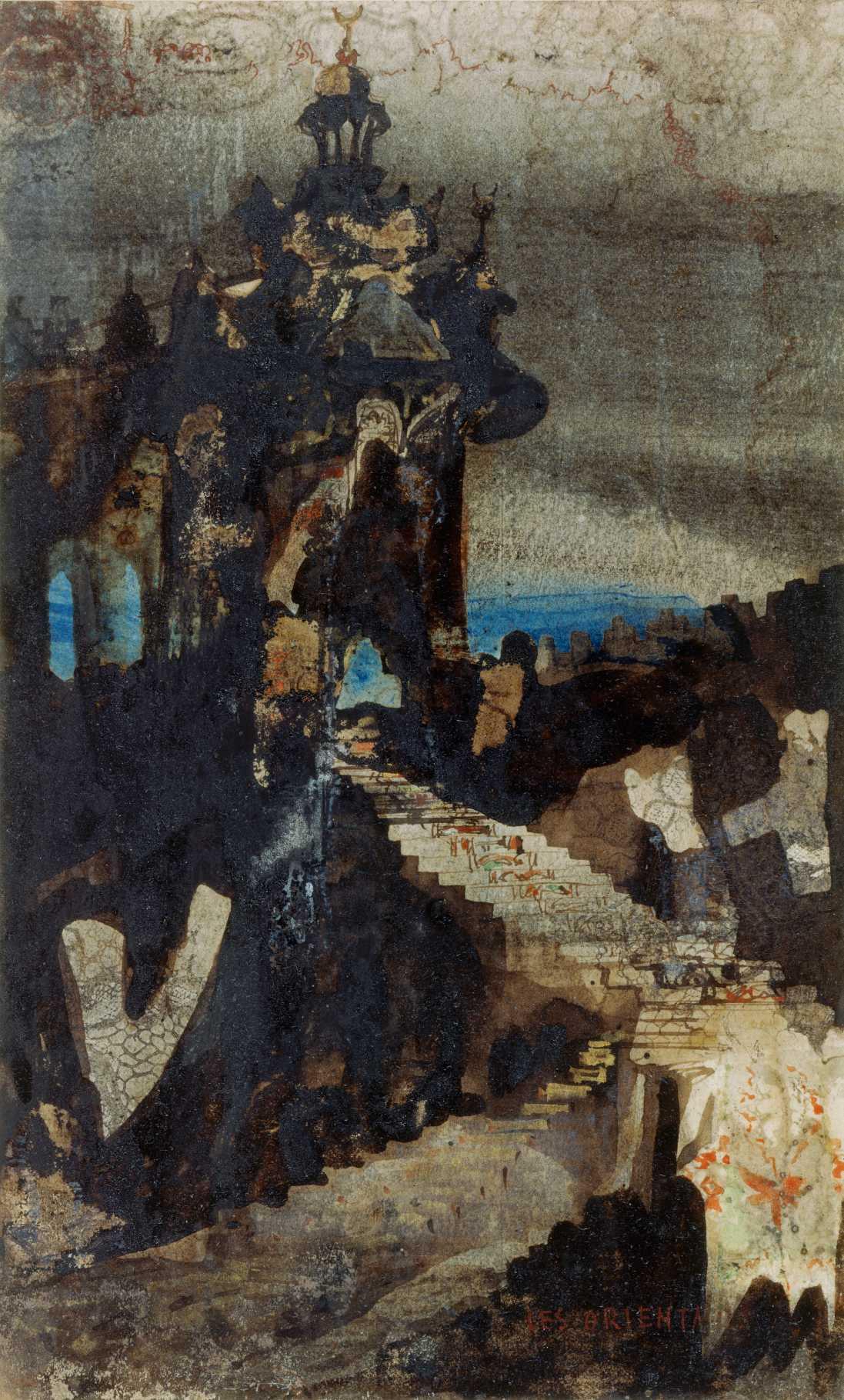

Since the nineteenth century, the fantasized Middle and Far East known as Orientalism has shared with the feudal era the feature that they are both “elsewheres,” places located outside the industrialized west: the first in geographic terms, and the latter in historical ones. A number of authors and artists who were fascinated by medievalism also produced orientalist work (Victor Hugo, for one, with Les Orientales, published in 1829, and The Legend of the Ages, composed from 1855).

This bond can also be found in twentieth and twenty-first-century fantasy. Among the earliest major films associated with the genre are works loosely based on tales and legends from the Levant, like The Thief of Bagdad (Raoul Walsh, 1924). In Game of Thrones (HBO, 2011-2019), scenes showing the Night’s Watch, vaguely reminiscent of military orders like the Templars, sometimes follow other scenes featuring sundrenched brothels in King’s Landing or the oriental gardens of Dorne.

Traveling through Time...

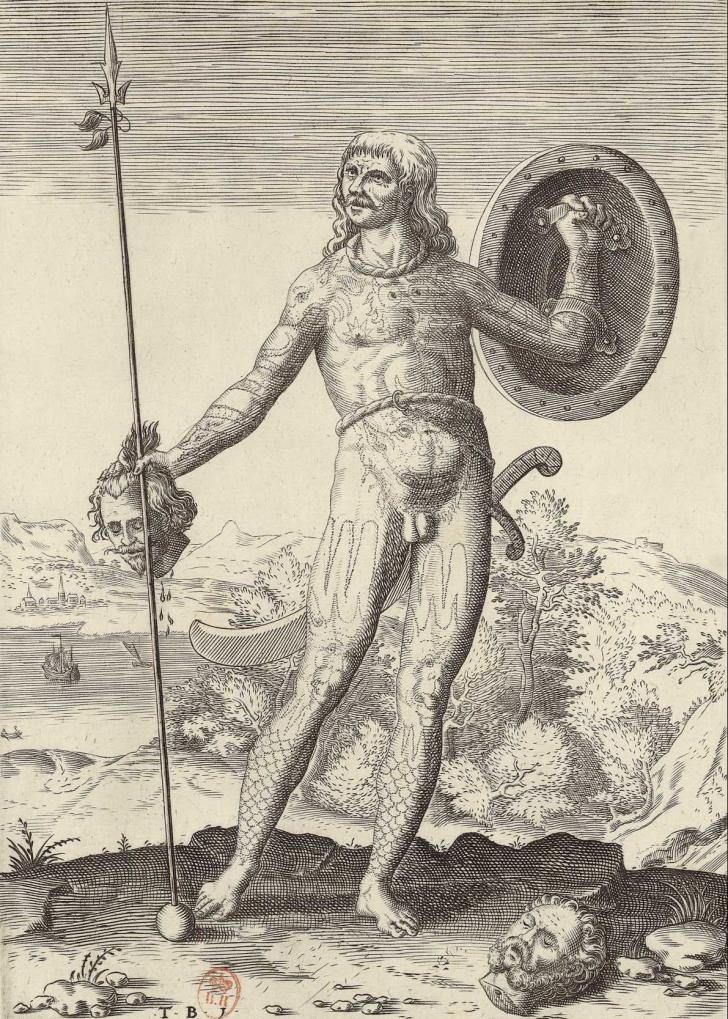

The Middle Ages is not the only historical period that has been recruited by fantasy. In the 1930s, Robert E. Howard created a prehistoric world for the adventures of his hero Conan. In it, we can encounter populations evoking Native Americans (the Picts), ancient Egyptians (the Stygians), Celtic warriors (the Cimmerians), medieval knights (the Aquilonians) and buccaneers that seem to have stepped straight out of a swashbuckling novel set in the eighteenth century.

A comparable hodgepodge of eras can be found in Game of Thrones, which has ancient towns with ziggurat-like step-pyramids towering over them (Meereen) coinciding with medieval cities like King’s Landing, while the Iron Islands are a nod to both the Vikings and the pirates that plied the Atlantic Ocean. All of those eras share with medievalism the idea of being pre-industrial “elsewheres” for the modern world. So bringing them together poses no problem… All the less so in that for decades, they each enjoyed their own literature genre – swashbuckling novels and westerns – which produced assemblages of stereotypes that fantasy authors can delve into at will.

Fantasy’s layering of historical eras also has a narrative purpose. By traveling, the hero goes not only to a different place, but also to a different time. In The Lord of the Rings, the Hobbits departing from the Shire are leaving a place that is reminiscent of the English countryside in the Victorian era to head deep into kingdoms that seem to have stepped straight out of medieval tales set in the tenth century. Similarly, Harry Potter (J.K. Rowling, 1997-2007) flees a banal contemporary suburban landscape of single-family dwellings for adventures in a world of witches regulated by rules that have remained unchanged since the Middle Ages. In this way, the fantasy experience is assimilated with a journey, not only through space, but also through time, precisely in an era when mass tourism and the growing uniformity of global culture are sapping changes of scenery of the eye-opening, marvelous nature they had in the nineteenth century.

... and within Other Mythologies

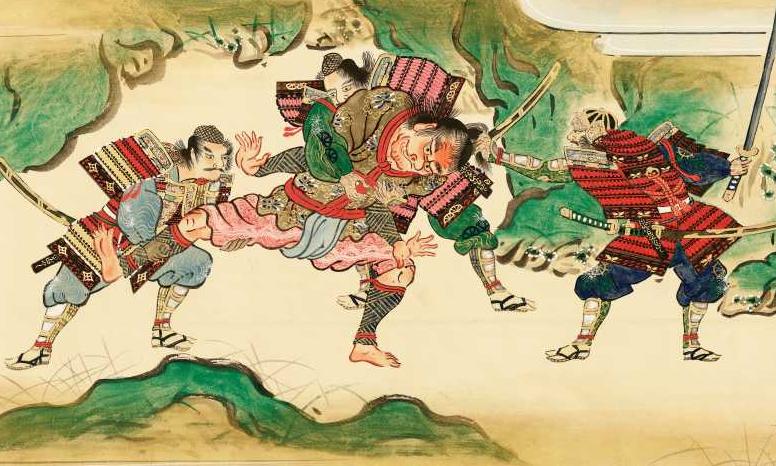

Yet historic fantasy is not limited to the past as seen through western eyes. As authors from other continents have taken hold of the genre, they have drawn inspiration from eras that are perceived as the antithesis of modernity in their own local context. In Japan, they chose the samurai era, all the more naturally in that it has been viewed as an Oriental counterpart to the western world’s Middle Ages since the late nineteenth century. The film Tales of Ugetsu (1953) by Kenji Mizoguchi is a perfect example of that, as is Hayao Miyazaki’s anime film Princess Mononoke (1997), both of which take place during the Muromachi period (early fifteenth to late sixteenth centuries).

The development of non-European-based fantasy worlds has also been influenced by the presence of ancient epic texts that local authors can spin off from. In India, the Mahabharata (an epic that is believed to have been written in the fourth century) has inspired a great deal of fantasy. The recent hit film series Baahubali (launched in 2015), for instance, is set in an archaic India that is similar in many ways to European Antiquity.

The future – often a post-apocalyptic one, in which modern civilization has been destroyed and the survivors have gone back to a technological level not unlike the Middle Ages – has also inspired fantasy. That vision represents the culmination of a process that began in the nineteenth century. It flourished in the 1970s, with animated films like Wizards (Ralph Bakshi, 1977) and the world based on the book series Shannara, which was started by Terry Brooks that same year.

Confronted with a forward-thinking modern world that insists that progress and change are ineluctable, fantasy instead expresses anxiety about that headlong rush forward, offering us a chance to fulfill a need – at least while we are reading – to escape modern life and return to a past that is seen as unchanging and filled with marvels.