Medieval Literature and Fantasy: A Wondrous Story

Although many centuries have gone by since the Song of Roland, the ties that bind medieval literature and the fantasy genre have not melted away. Magical enchantments and marvelous wonders are among the most striking bridges between the two genres.

While the wondrous in fantasy is defined by a magical character that is necessarily perceived as unreal in our society of scientific rationality, in medieval times, the wondrous referred to phenomena that were out of the ordinary, but generally related to a divine order. That significant difference does not prevent the existence of an important bond between the marvelous in tales from feudal times and in fantasy, if only because several early authors of the genre, including both William Morris and J.R.R. Tolkien, were devoted readers of medieval literature.

Journeys: Cornerstones of Marvelous Tales

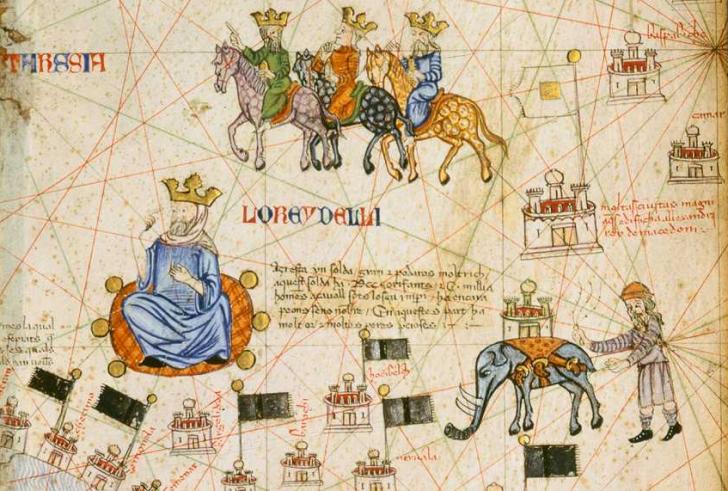

In medieval tales, magical and marvelous occurrences were usually connected with journeys: knights leaving courts for forests filled with mysterious creatures for instance, or merchants and pilgrims traveling to distant lands. The Orient, in particular India at first, and later China, were some of the largest suppliers of magical creatures for artists sketching “mappae mundi,” symbolic maps of the world with fabulous creatures scattered across them.

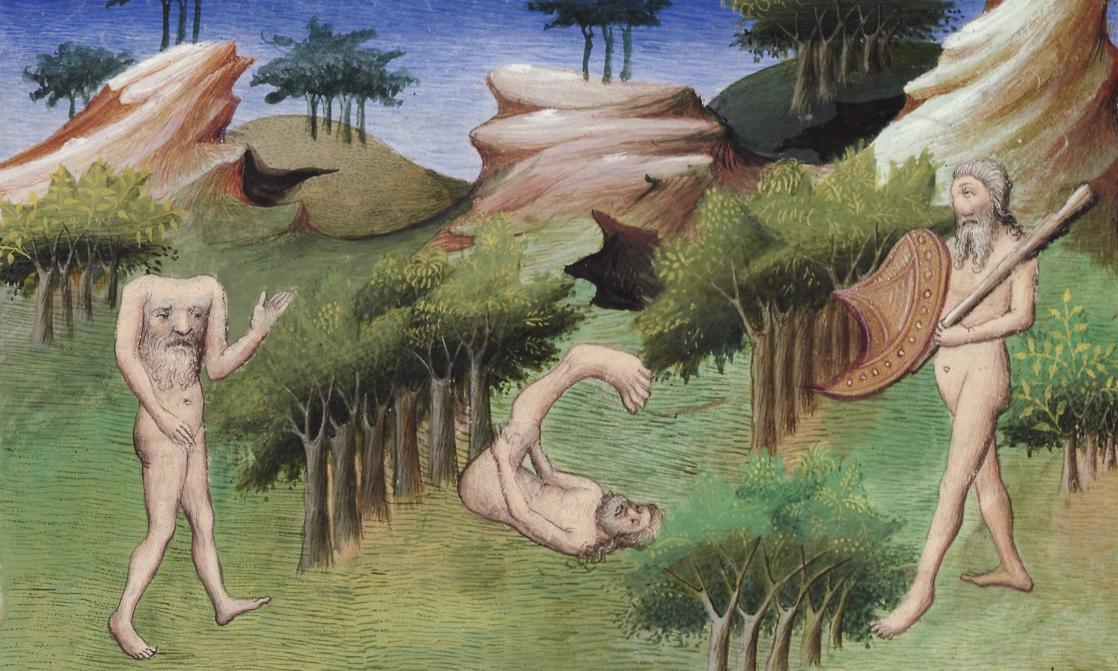

Traveler-writers would not be outdone, however. Some medieval manuscripts of The Travels of Marco Polo, an account as told by Marco Polo himself in the late twelfth century, are known by the title Book of the Marvels of the World. The text even begins with, “Read this book: in it you will find very great and wonderful things of the nations, chiefly of Armenia, Persia and Tartary, India, and various other provinces.” The Oriental lands described in it are sometimes populated with marvelous creatures, like cynocephali, or dog-headed men. The artists who illuminated Polo’s tales took it upon themselves to accentuate the strange Levantine landscapes by adding creatures unmentioned in the text, like the Blemmyes, a race of headless people, or the Sciapods, a tribe whose members had only one foot. In western Medieval culture, strange beings like those constituted the very essence of the marvels associated with the Levant. Modelled on Marco Polo’s text, many travel journals were also named Book of Marvels, like the explorer Jean de Mandeville’s (sixteenth century), which is sometimes incorporated into the same manuscript as Marco Polo’s text.

Fantasy is in fact often presented as a travel narrative in which the hero leaves a well-known center to head towards wondrous, magical lands on the distant outskirts. The most famous example of that, hands down, is The Hobbit (1937), followed by The Lord of the Rings (1954-1955), both by J.R.R. Tolkien, whose main characters, little hobbits living in a region reminiscent of the nineteenth-century European countryside, leave their native land to embark on a quest. Along the way, they will encounter dangers and monsters of all sorts. The passage from The Two Towers (the second volume of the novel) in which Samsaget Gamgie catches sight of an oliphant is quite revealing on that score:

“To his astonishment and terror, and lasting delight, Sam saw a vast shape crash out of the trees and come careering down the slope. Big as a house, much bigger than a house, it looked to him, a grey-clad moving hill. Fear and wonder, maybe, enlarged him in the hobbit's eyes, but the Mumak of Harad was indeed a beast of vast bulk, and the like of him does not walk now in Middle-earth.”

Who Says Size Doesn’t Matter?

Here the magical is associated with hyperbole, with such outrageous excess that it becomes rare. This feature is often found in epic medieval texts, in which armies are composed of hundreds of thousands of warriors. "Now marvellous and weighty the combat, Right well they strike, Olivier and Rollant, A thousand blows come from the Archbishop's hand, The dozen peers are nothing short of that, With one accord join battle all the Franks. Pagans are slain by hundred, by thousand,” wrote the author of The Song of Roland (late eleventh century).

A similar process of accumulation of numbers is used in Marco Polo’s Book of Marvels, when he describes the Chinese emperor Kublai Khan’s hunting parties. “In that time he had assembled good 360,000 horsemen, and 100,000 footmen,—but a small force indeed for him, and consisting only of those that were in the vicinity. (…) If he had waited to summon all his troops, the multitude assembled would have been beyond all belief, a multitude such as never was heard of or told of, past all counting.”

Thus size is another way to indicate that something is magical. Medieval texts contain references to countless colossal constructions, huge beasts and giants, who, in The Song of Roland, for example, fight alongside the Saracens. Analogic medieval thought paired huge size with seniority or great age. So this is how the body attributed to King Arthur that was unearthed in Glastonbury Abbey in the late twelfth century was described by the historian Gerald of Wales, who was alive at the time of the discovery, “For when his shin-bone was placed beside the shin of the tallest man of the locality […] it came three big fingers’ width above his knee. His skull, too, was large and capacious like a prodigy or wonder, to such a degree that the space between the eyebrows and between the eyes was more than a palm’s width. Fantasy has adopted this process in turn. Thus the Wall in A Song of Ice and Fire (George R.R. Martin, since 1996) is over 700 feet tall and was built nearly eight millennia ago.

Not-So-Distant Marvels

In the Middle Ages, magic was not always far away. When it was near to hand however, it was confined to particular places, like the islands and forests where Arthurian knights rode off to find adventure. The magic that is found there strikes us less as a change of landscape than a change of era, so powerfully does it appear to be a relic of the pre-Christian past. It is not, however, necessarily connected to Norse paganism. The Chronicle of a Monk from Saint-Denys, written in the early fifteenth century, recounts that in 1380, King Charles VI of France encountered a stag in the forest of Senlis. The beast bore a collar engraved with an inscription in Latin asserting that the object had been bestowed upon him by Julius Cesar. The king was informed that the animal had indeed been living in those woods since that long-gone era. That, too, is a common motif in fantasy, with its countless forests filled with millennia-old elves. Robert Holdstock’s Mythago Wood, a novel published in 1984, is also based on the idea that sylvan magic induces a kind of time travel, enabling us to encounter archaic legendary creatures.

These examples show that it is possible to establish a family tree connecting the wondrous in the medieval era to contemporary fantasy. Yet the two do not play the same role. The former was understood as being part of the divine order, which although far off, its presence could still be spotted in the margins… of pages, territories and Christendom. In fantasy, the wondrous is assimilated to imaginary creations symbolizing our lost pre-industrial society. So its portrayals are accompanied by nostalgia for the natural world that modern people have lost touch with. Tolkien’s elves, for example, are supposed to catch the last vessels to reach the territory of Valinor; while near Westeros, in A Song of Ice and Fire territory, "Magic had died in the west when the Doom fell on Valyria and the Lands of the Long Summer."