Magical Books and the Power of Imagination

Reading a good book of any kind is always synonymous with taking off for elsewhere. But fantasy often takes that metaphor literally, with heroes literally diving into the world of books.

The Neverending Story, or the Magic of Creative Imagination

Fantasy for young readers presents reading and imagination as powerful kinds of magic that open the doors to worlds brimming with wondrous marvels. The Neverending Story (1979), by German novelist Michael Ende (film adaptation by Wolfgang Petersen, 1984), is surely the most iconic example of that motif. In it, Bastian, a shy, bullied boy who is neglected by his father after the death of his mother, is captivated by a magical novel called The Neverending Story. In the book-within-the-book, Bastian finds out about his doppelganger, the hero Atreyu, who is on a Great Quest. The goal is to save the magical land of Fantasia, a veritable “storyland” populated with all sorts of creatures, but one that is gradually vanishing because not enough humans believe in it any more. At first, the two worlds are distinct, but Bastian eventually literally enters the story: having turned into a character in the story, he realizes that he is very powerful. He can grant existence to things by naming them.

So the novel celebrates the magic of creative imagination, of reading in a way that brings a text to life. Still, it also warns of the parallel danger of the appeal of escapism. Before returning, transformed, to our world, Bastian was nearly lost to his own dreams of omnipotence.

The Enchanted Worlds of Books

The idea that fantasy’s other worlds are equal to products of human creativity is omnipresent. In Pierre Bottero’s La Quête d’Ewilan trilogy (“Ewilan’s Quest,” 2003), the magical dimension at the root of the heroine’s power is called “Imagination.” Heroes’ journeys through the other worlds they fall into also work as reflections of readers’ journeys through fiction – particularly through enchanted children’s stories. Fairy tales and legends are the archetypes of those primordial stories that allow us to rediscover a magical relationship with things. Even in movies, when they want to bring spectators into the “enchanted world of fairy tales” – usually to parody them – they start with an image of a book opening. The camera zooms in, plunging us to the heart of the words. The Princess Bride (Rob Reiner, 1987), Shrek (2001), and Enchanted (Kevin Lima, 2007) all flaunt their fairy-tale roots that way, right from the opening sequence.

The German novelist Cornelia Funke’s Inkworld trilogy (2003-2007) is another tribute to the power of reading. Meggie inherits her bookbinder father Mo’s gift for opening the doors between the word of books and the real world by reading books out loud. She summons characters from the 1,001 Nights and Peter Pan, and allows heroes from our world to enter the world of an imaginary book called Inkheart.

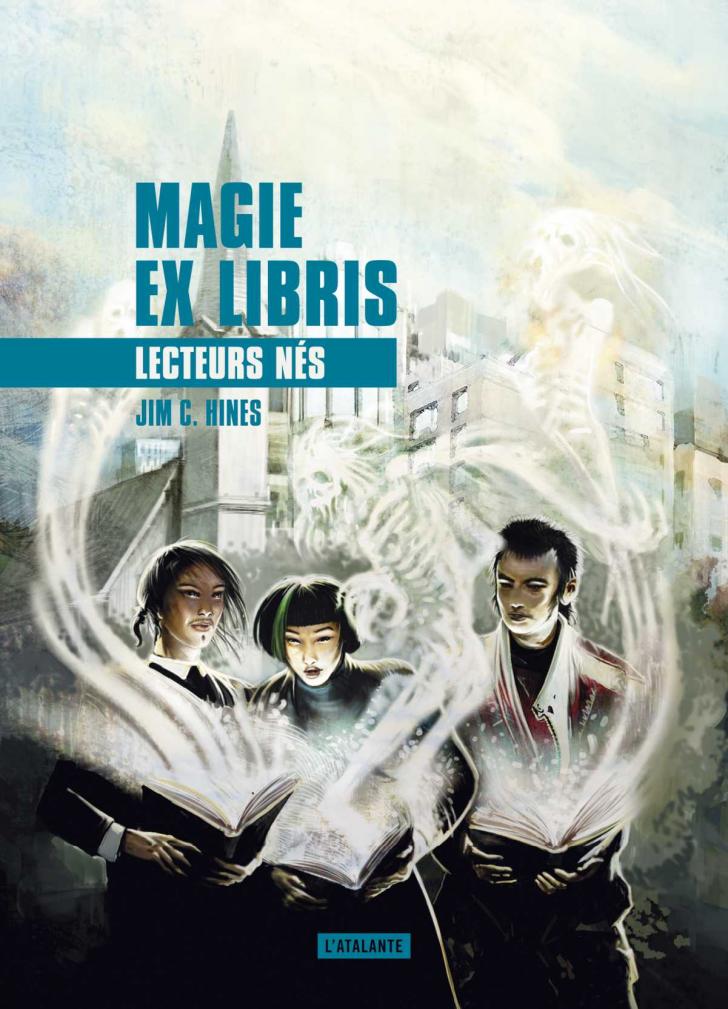

John Connolly’s Book of Lost Things also offers a lovely story about entering a fairy-tale world that is darker than it seems at first glance. The journey includes an initiatory dimension for the young hero, who has been struggling since his mother’s death. Less frequently, the opposite logic, in which readers’ love grants magical power to books, enabling creatures and objects to emerge from them into our world, can also be found. In Jim Hines’ Magic Ex Libris series (since 2012), Gutenberg was the first person to take advantage of that ability, and the Libriomancers protect our world from the power and danger of the inventions found in fiction!

Dreams and Games: Dizzying Immersion

Fiction’s self-celebration of its own powers and dangers isn’t limited to the above examples however. Musings about the illusions, comforts and traps that console and haunt us can also adopt dreams as a vector (Catherine Webb, Mirror Dreams, 2002), or, quite frequently, games. In the video game Myst (Robyn and Rand Miller, 1993), a quest for “linking books” makes it possible to move from one world to another thanks to “The Art.”

The “virtual reality” of video games, and the replacement life that young generations find in them, also constitute a terrain that has been extensively explored in fantasy books for teens and young adults. A number of books with stunning art, like Codex (Lev Grossman, 2004) and L’Attrape-Mondes (“World-Catcher,” Jean Molla, 2003), illustrate a dizzying confusion between the nature of reality (where does it begin and end), that concerns even the hero’s identity (who is the avatar? who is the player?).

Fantasy is often seen as a form of escapism; but once childhood has passed, escapism can look a lot like avoiding the responsibilities of daily life. So the genre has taken the issue head on. Although it continues to honor the inner resources that the power of imagination can offer, it now also urges young consumers of magical fiction to consider their motivations for doing so, in order to find firm ground for exploring their own potential in the real world.