Fantasy in France: The Road Goes Ever On

Although it has existed in France for decades, fantasy had to wait for the turn of this century to gain recognition as a singular genre, thanks to the work of fervent fans and small, independent publishers.

A Belated Appearance in Publishing

A lack of identification is the main cause of fantasy’s belated arrival in France. For although a great number of books had been published, no specific collection existed to contribute to their visibility. The word “fantasy” wasn’t even in use yet.

Which explains why J.R.R Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (1954-1955) wasn’t published in France (by Christian Bourgois Editeur) until 1972-1973 – considerably later than in the rest of Europe. The great series only reached us in the orbit of other genres. First through the fantastique, with Opta’s “Aventures fantastiques” collection, then through science fiction.

Jack Vancel’s series were translated by the “Club du Livre d’Anticipation” (Social Sci-Fi Book Club), Roger Zelazny’s Chronicles of Amber by “Présence du Futur,” then in “Folio SF.” In fact, for many years, the name “science fiction” dominated French publishing, acting as a catch-all category, including even what would be introduced in the 1980s as “heroic fantasy.”

It wasn’t until the late 1990s – early 2000s that the word “fantasy” (in English) caught on, as book collections and publishing houses specifically devoted to it, like Nestiveqnen and Mnémos, begin to appear in the wake of role-playing game publishers. In 2000, the publishing house Bragelonne launched with authors like David Gemmell and Terry Goodkind, who had not yet been published in French, giving itself a good start and a chance to expand.

The Importance of Hard-Core Fans

Groups of fans kept fantasy alive in France at that time. Several players entered the “micro-publishing,” market, a dynamic yet extremely fragile sector. More and more festivals and fan groups cropped up on-line, and had soon been recognized as the best sources of information about the genre.

The sector’s growth and French readers’ increased knowledge then led to publishing houses making fantasy’s heritage available. That meant everything from the first French translations of William Morris’s work, published by “Aux forges de Vulcain,” to a range of complete series proposed by Bragelonne, Pocket, J’ai Lu, and others), and even retranslations that bear witness to a new, more respectful attitude towards the original texts, with Patrice Louinet’s work on Robert E. Howard’s oeuvre, David Camus’s on H. P. Lovecraft’s, and Daniel Lauzon’s new translations of Tolkien.

Fantasy à la française

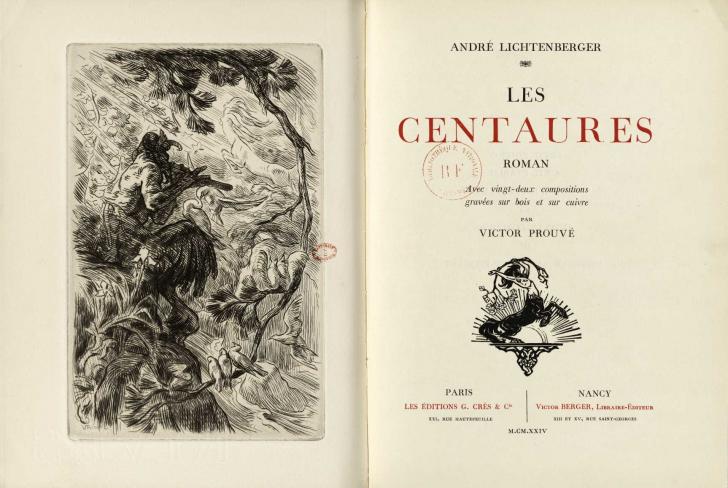

Books written in French by French-speaking authors were long considered “second-tier,” however. Having arrived somewhat late on the scene, they had trouble making a place for themselves in the world of translation. But French-language production has now reached full maturity. Lately, some earlier, overlooked French fantasy – like The Centaurs (André Lichtenberger, 1904) and Francis Berthelot’s Khanaor diptych (1983) are getting rediscovered. And once again, it was in the late 1990s that the “new French school” of fantasy clearly emerged. It is very well represented by the trio composed of Mathieu Gaborit (Les Chroniques des Crépusculaires (Dusky Chronicles), 1995-1996), Fabrice Colin (Arcadia, 1998, Winterheim, 1999-2003) and Henri Loevenbruck (La Moïra and Gallica, since 2001).

Publishing houses now welcome French authors with singular and exacting imaginations. Volte Publishing wecomed Alain Damasio and his famous Horde du contrevent (The Into-the-Wind Horde) 2004), and Les moutons électriques, run by André-François Ruaud, which has accompanied Jean-Philippe Jaworski’s career for his Tales from the Old Kingdom, which include “To the Victor Go the Spoils,” (since 2007) and Kings of the World (since 2013).

Other independent editors have managed to make names for themselves too, like Scrinéo, who publishes Gabriel Katz, among others; ActuSF, with Karim Berrouka, and Critic,’ with Estelle Faye and Lionel Davoust. Lastly, the sector’s more established players have also contributed to letting French talent flourish: L’Atalante, with Régis Goddyn; and Mnémos, with, for instance, Adrien Tomas and Charlotte Bousquet, as well as Bragelonne, particularly with Pierre Pevel. The latter is an important representative of the French dramatic/serial tradition; he pays tribute to it in his Ambersea Enchantments series (2003), which channels the spirit of Arsène Lupin; and The Cardinal’s Blades (2007), which summons Alexandre Dumas. The latter was actually the first French fantasy series to turn the tide and be translated and published in the United States.