From the Aristocracy to the Playground: A Short History of Fairy Tales

Emerging from an oral storytelling tradition, written, literary fairy tales first appeared just over three centuries ago. Originally intended for adults, the genre gradually evolved into a major elements of children’s literature.

A Late 17th Century Literary Trend

The history of fairy tales, even from well before the birth of fantasy, is already a story of constant re-discovery. Typical of oral cultures, they probably figure among humanity’s earliest stories. As simple folk’s alternative to myths and epic poetry, they offered entertaining or terrifying stories that included moral messages to a broad audience.

Yet from the moment they were put into writing, they became a highly literary genre. Granted, Charles Perrault, whose Tales of Mother Goose (1697) included “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Tom Thumb,” “Cinderella,” “Puss ‘n Boots” and more, instantly conjures up an image of an old nanny telling stories by the fireside. Nonetheless, it should be remembered that those tales in poetry and prose are the work of a classically trained author who was a contemporary of Louis XIV. Perrault also composed elegant odes and portraits of powerful people that were aimed at an adult and aristocratic readership; both his style and his stories’ morals were the product of careful reflection.

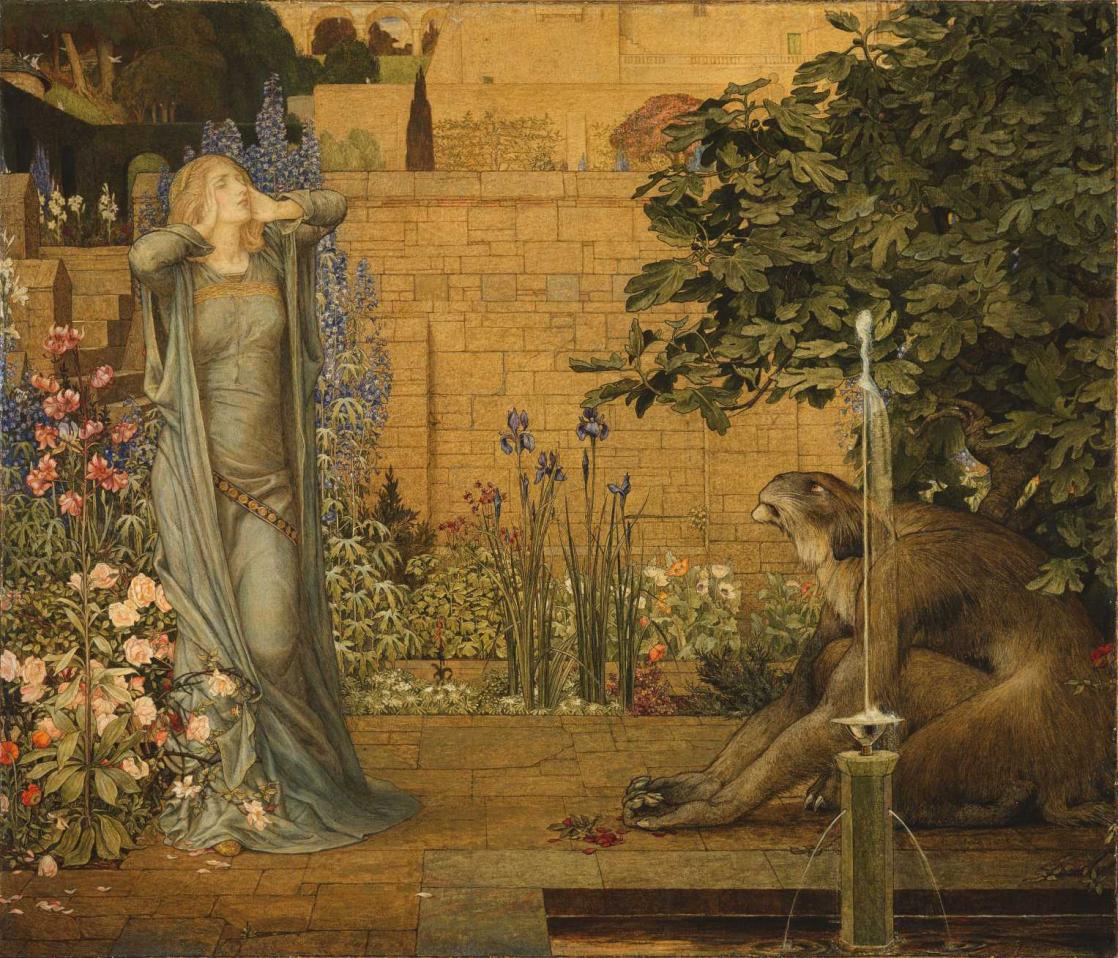

At the same time, a generation of female story-tellers, like Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier, Henriette-Julie de Murat, Charlotte-Rose de Caumont La Force, and above all, Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy, a trailblazer with her tale l’Île de la Félicité (1690) and the author of Contes nouveaux ou Les fées à la mode (“New Tales or Fashionable Fairies” 1697-1698), takes hold of this new form, which will remain lastingly associated with a feminine influence on storytelling. Writing not for children, but for their own peers – socialites and educated women – they slipped barely veiled risqué references into “La Chatte Blanche” (“The White Pussy”) and “Le Serpentin vert” (“The Green Serpent,”) love stories with animal metamorphosis.

The Eighteenth Century’s Reinvention of Fairy Tales

Those first written fairy tales, sophisticated and intended for adult readers, composed a significant mass of text, as one can see from the 41 volumes compiled from 1785 to 1789 by Chevalier de Mayer: Le Cabinet des fees (“The Fairy Cabinet”). A bowdlerization of the genre can be seen, as the libertine vein is eliminated. Over the course of the century, fairy tales gradually turn towards the more youthful readership that is just starting to emerge, but will continue to grow. The genre’s moral aspect lends itself perfectly to the era’s new educational concerns, and the French Encyclopedists’ cult of reason tended to associate all things magical and wondrous with childhood and the darkness of ignorance that precede the age of reason and its “enlightenment.”

And so Beauty and the Beast, first penned by Gabrielle-Suzanne de Villeneuve in 1740, became successful in a shortened version for children, the one by the schoolteacher Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont, which was published in 1757 in Le Magasin des enfants, ou Dialogue d'une sage gouvernante avec ses élèves (“The Children’s Magazine: A Wise Governess’s Dialogue with Her Charges”).

In Search of Oral Folk Roots

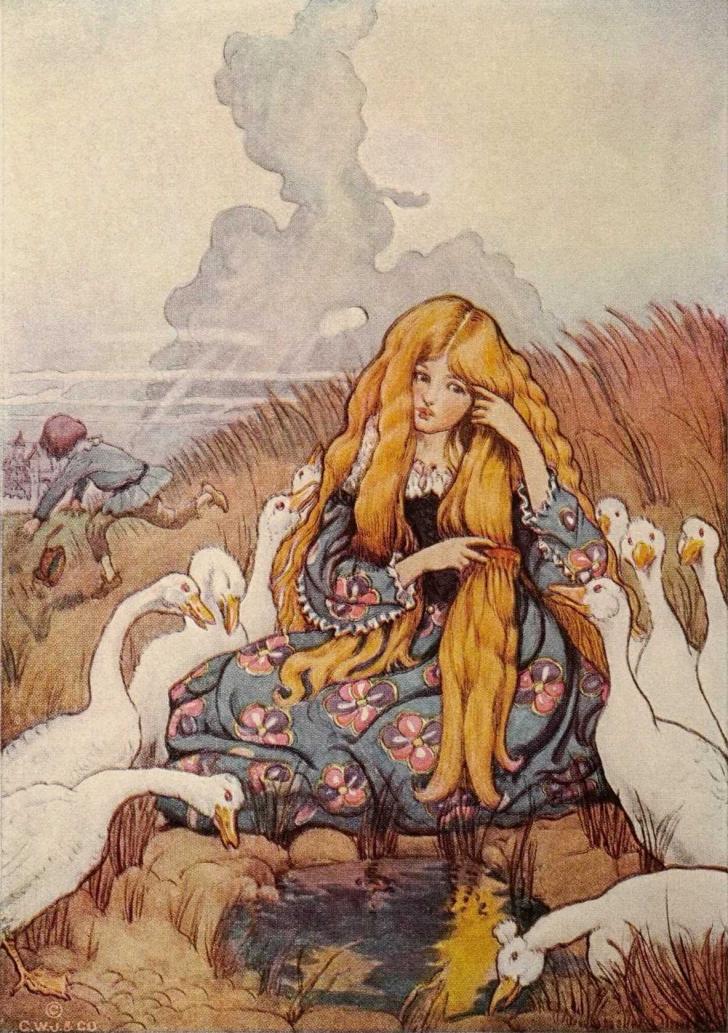

By the late eighteenth century, in a context of renewed appreciation for national cultural heritages, the first generation of folklorists began to proclaim the importance of preserving traditional tales. Their goal was twofold: both to preserve a trace of that legacy and to study it. In Germany in 1812, the Brothers Grimm would publish Grimm’s Fairy Tales, (originally known as the Children's and Household Tales) their first anthology of oral folklore, which they had collected in the countryside.

We now know that the Brothers’ quest for the original folk versions was partly skewed – not only because literary composition is clearly not absent from their work, but also because they collected many tales from a family with French roots that had gone into exile during the Revolution. The Brothers’ work influenced other folklorists, such as the Russian Alexander Afanasyev (eight volumes from 1855 to 1867), and to this day one can still find collections of the tales and legends of various regions of France.

Insofar as oral cultures are never entirely impervious to outside influence, the tales we know are always reconstructions that inevitably bear a trace of the spirit of the times in which they were produced. While the “original,” or “primitive” version will remain forever out of reach, at least we can multiply variations.