Romanticism in British Literature: The Fantasized Middle Ages

Largely idealized and romanticized by the Romantic authors, the Middle Ages were not fantasized for aesthetic purposes only. The liberties taken often served as a screen for criticism of modern life.

The Western World’s Two “Elsewheres”

The early-nineteenth-century Romantic authors are largely associated with rediscovering the Middle Ages and creating a fantasized reinterpretation of them that is known as “Medievalism.” The phenomenon is indebted to one of the key figures in the movement, the Scotsman Walter Scott, and his fascination for the feudal era. Scott’s first taste of fame came in 1805, thanks to his long narrative poem The Lay of the Last Minstrel, before going on, in 1819, to write the novel Ivanhoe, which met with success from France to the United States.

Scott was not the only author interested in that period. In 1816, Samuel Taylor Coleridge published two important poems or ballads, Christabel and Kubla Khan. The latter was devoted to the thirteenth-century Mongol emperor Kublai Khan and his summer palace, Xanadu. In the early nineteenth century, the fantasized vision of the Middle Ages intertwined with an equally fantasized one of the Orient (Orientalism) to create a dual “elsewhere” for the western world, one historical, the other geographical.

A Reaction to the Enlightenment

This sudden fascination for a period that had mostly been inspiring disdain for the preceding three centuries can be understood first and foremost as an aesthetic and political response to the Enlightenment. Although eighteenth-century philosophers glorified Antiquity, some of the Romantics saw the Middle Ages as an ideal period, one in which social stability reigned. The idea, which was first put forward by the conservative philosopher Edmund Burke – who, after the fall of the Bastille, announced that “the age of chivalry is gone” – made a lasting impression on Walter Scott. The novelist man sang the praises of the old aristocracy in both Quentin Durward (1823) and The Talisman (1825).

Nevertheless, other Romantics from that era, including Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Keats, made their affinity for radical schools of thought clear. For them, Medievalism was above all a tool to be used to criticize the adverse effects of the Industrial Revolution. They saw it as a response to the mercantilist rationalism of London’s entrepreneurs.

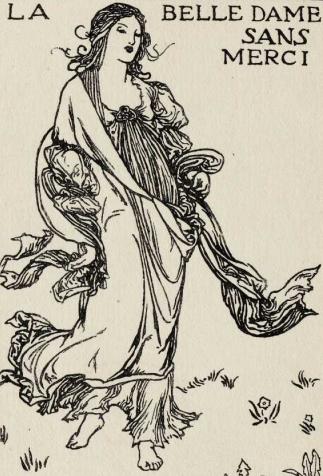

They enjoyed portraying a medieval world of wondrous marvels, as in La Belle Dame sans Merci, which Keats wrote in 1819, based on a fifteenth-century French text. For the English writer, the practice of art, associated with the medieval figure of the poet contrasts with that of the modern businessman, concerned only with numbers. A similar notion is expressed in Queen Mab, a philosophical poem (1813) by Percy Bysshe Shelley, in which a fairy from the Middle Ages (period extolled by both Chaucer in the fourteenth century and William Shakespeare in the sixteenth) announces the imminent arrival of utopia.

Romanticism and Fantasy

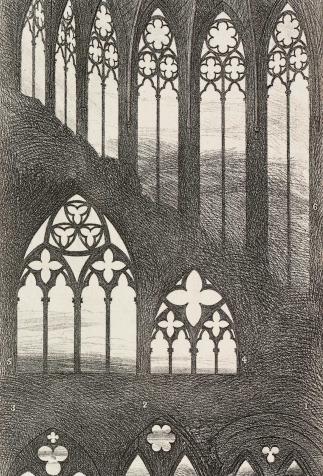

The poets’ connection between criticism of the industrial world and medievalism held great sway over the English art critic John Ruskin and the pre-Raphaelite painters. Some of the latter chose to paint La Belle Dame sans Merci (John Keats, 1819), while Ruskin sang the praises of medieval artisans’ joyful life, the better to criticize the oppression suffered by modern factory workers. William Morris was inspired by it when he was writing poetry, before he began, late in life, to write novels set in imaginary medieval worlds, precursors of J.R.R. Tolkien’s and C.S. Lewis’s magical worlds.

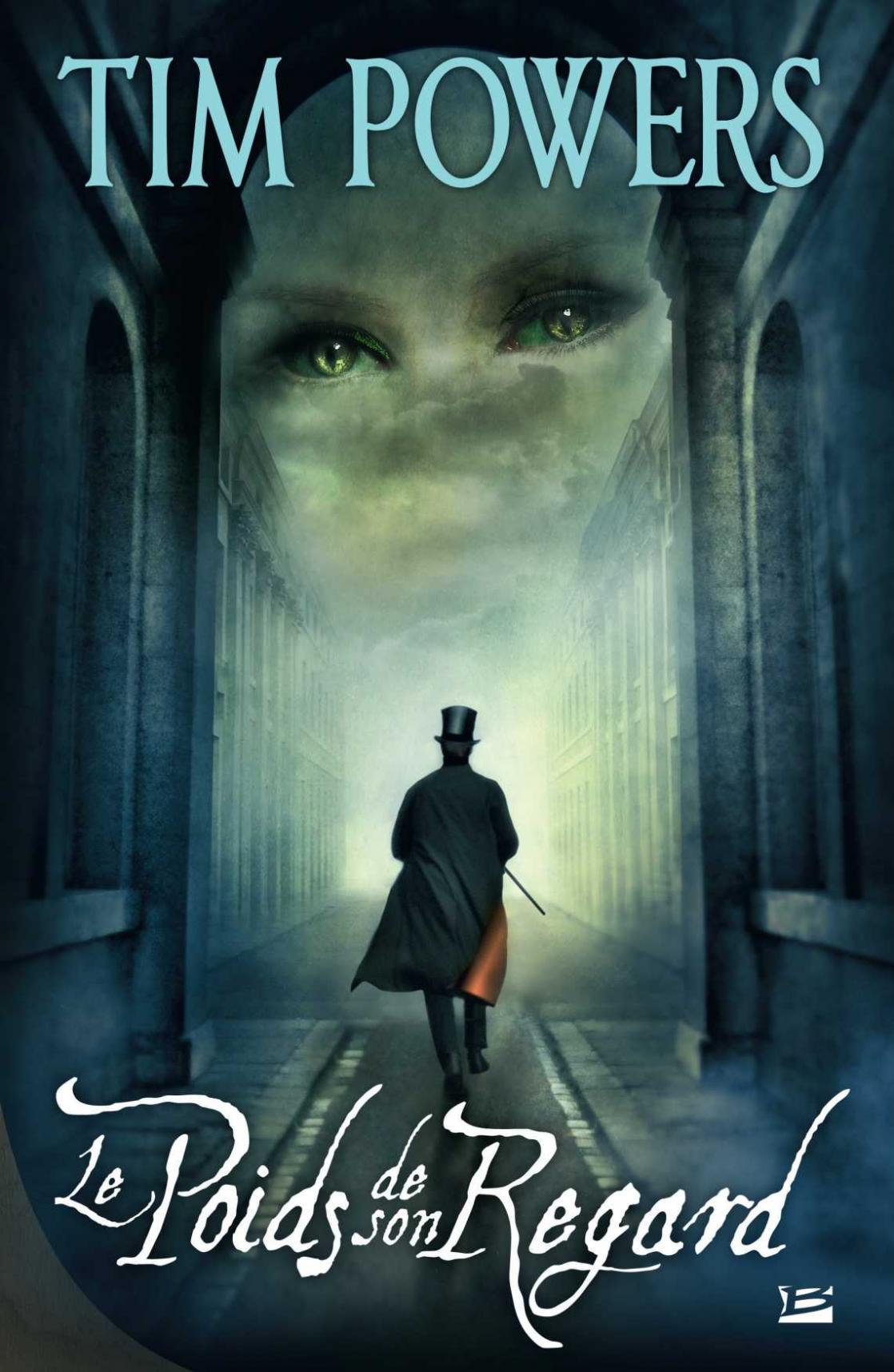

The radical Romantic poets’ fascination with the phantasmagorical even led some later fantasy authors to turn them into colorful fictionalized characters. In his novel The Anubis Gates (1983), Tim Powers turns Samuel Taylor Coleridge into a hero fighting a vast plot by eastern magi, and in in The Stress of Her Regard (1989), he has Lord Byron and John Keats fighting vampire-like creatures. Those tales had a tremendous impact on both the steampunk genre and its magical counterpart, gaslight fantasy.

As for Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell (2004), it features a Byronic hero who could easily have been modelled on Byron himself. The book, which the BBC adapted into a mini-series in 2015, portrays the British Isles during the Napoleonic Wars as being torn between the Industrial Revolution and the last gasps of the world of magic that refuses to give up the ghost, as it were. In the novel, the practitioner of witchcraft, final heir to a centuries-old tradition, reminds one of the figure of the Romantic poet fascinated by medievalism, a tragic character struggling to have his concerns about the upheavals of the modern world heard.