Magic at the Heart of the Genre

Accepted as perfectly natural, normal phenomena, magic, enchantment and the supernatural are an integral part of fantasy worlds and a defining feature of the genre.

The presence of magic and enchantments are among fantasy’s most defining features: in fantasy worlds, those elements are not only acknowledged and accepted by all, they are practiced regularly and even taught in school. So Harry Potter (J.K. Rowling, Harry Potter, 1997 - 2007) has to attend Hogwarts “School of Witchcraft and Wizardry” in order to learn to master the powers he was born with. Schooling in magic is an extremely common motif in fantasy. It provides a convenient pretext for authors to initiate readers into the mysteries of their alternative worlds, by introducing the hero to them over the course of his or her education.

Magic and enchantments are so integral to fantasy’s worlds that they are no longer actually considered “supernatural.” The Memoirs of Lady Trent (Mary Brennan, since 2013) are a perfect example of this. The heroine, a natural historian, chooses to specialize in dragons, doing research into their means of reproduction and their classification into sub-species, as Darwin did with the more mundane finch.

Powers to Master

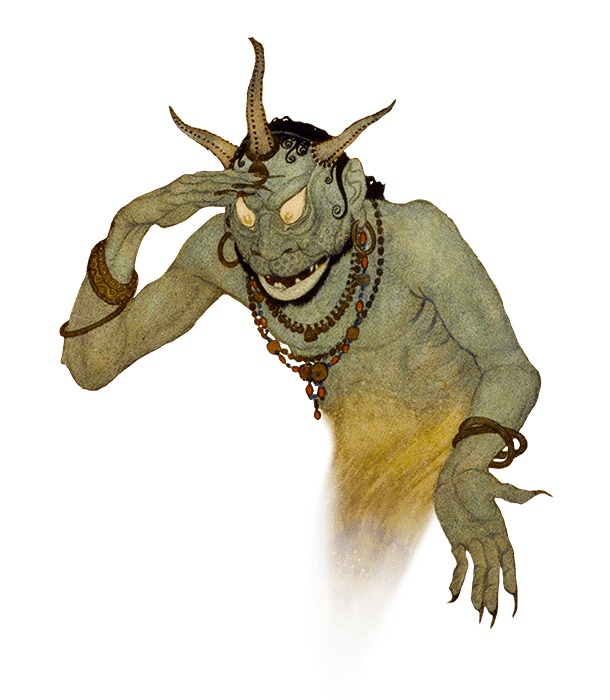

As natural as it may be, magic still comes in extremely varied styles whose limits are set only by the authors’ imagination. You’ll find fabulous creatures inspired by folklore and mythologies from around the (real) world or sprung fully formed from an author’s mind; magical objects, from wands and swords to rings and invisibility cloaks; worlds that can be accessed through magical knives (Philippe Pullman, His Dark Materials, 1995-2000), wardrobes that are actually portals (C. S. Lewis, Narnia, 1950-1956), or by following a fairy (Patrick Rothfuss, The Kingkiller Chronicle, since 2007); and a stunning array of both creative and destructive powers.

In addition to novels and comic strips, magic and enchantment also have starring roles in a large number of role-playing games, video games and even fantasy board games. The famous card game Magic: The Gathering lets players be witches summoning creatures and casting spells by “tapping” mana, or magical energy, from land cards. In many video games, magical power takes the shape of a magical-energy bar (which is also often called the mana), that empowers players to cast spells, but that needs to be recharged regularly. In any case, those powers are never available to just anyone. In MMORPG (massive multi-player on-line role-playing game) video games, like World of Warcraft, as in most role-playing games, you have to have a certain type of character in order to be able to wield magical powers. The ability usually comes at the price of physical weakness.

Identify the Supernatural or Let Doubt Linger?

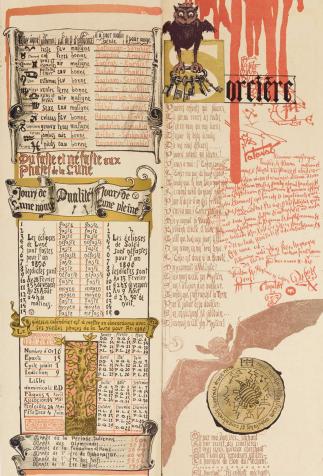

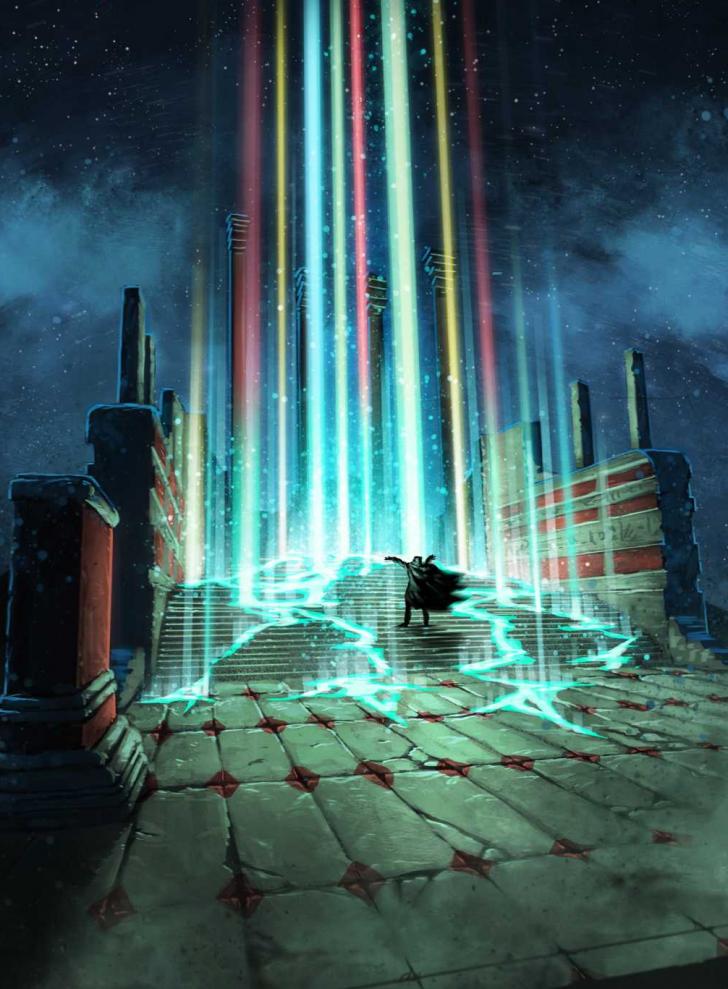

For fantasy authors, magic is both a gift and a real challenge. Some authors meticulously describe precisely codified systems of magic. Brent Weeks, for example, has established a color-based system (The Lightbringer Series, 2010-2019). Brandon Sanderson goes all out, reinventing a different kind of magic for each of his series; metal-based (in Mistborn 2010), gravity manipulation (for The Stormlight Archive, 2010) or by bringing chalk drawings to life (The Rithmatist, 2013). It is worth pointing out that several of the systems depend on knowing things’ “true name,” which grants power over the things themselves. (Ursula K. Le Guin, Earthsea, 1968-2001); Christopher Paolini, Eragon, 2003; Patrick Rothfuss, The Kingkiller Chronicle).

They are in fact more or less consciously echoing medieval and modern theories of an interpretation of the Book of Genesis that connects the power of naming to domination. Some fantasy writers prefer to shroud things in mystery. The famous magician Gandalf doesn’t really do any “magic tricks,” although he does handles fireworks with supernatural skill. Others find inspiration in traditional tales and legends, placing their stories halfway between fantasy per se and the fantastical. That is the case of Neil Gaiman, who has written several novels that adopt a “fairy-tale” narrative structure (The Ocean at the End of the Lane, 2013; Neverwhere, 1996; Stardust, 1999). The supernatural is sketched in rather than described precisely, bathing the whole plot in shadowy half-light.

In some narrative worlds, magic reigns supreme, and its practitioners rise to the top of the worlds’ social and political hierarchies. But often, on the contrary, magic is fading as other powers, like technology, are on the rise (that is the case in Michael Moorcock’s Chronicles of Corum, 1971-1974). In yet other sagas, it is actually staging a comeback, wreaking havoc on the world’s political and geopolitical equilibrium. The dragons’ rebirth in A Song of Ice and Fire (G. R. R. Martin, 1996) leads to magic’s reappearance throughout the known world. Like the protagonists of Everworld (K. A. Applegate, 1999-2001) and The Fionavar Tapestry (G. G. Kay, 1984-1986), characters are sometimes ripped from the everyday world and dropped into one where magic is real. In other novels, magic infiltrates our world, to the point of completely redsigning it, like in the Fever series (Karen Marie Moning, since 2006).

Time Is On Witches and Wizards’ Side

Magic can be positive or negative, or even both at once, depending on who’s wielding it. For a long time, fantasy pitted the brave hero, a fearless, but not necessarily very bright, warrior-knight against the evil witch or wizard. That conflict is summed up in the name of the “sword and sorcery” sub-genre itself, and is at the core of many novels in the Conan saga. That division descends in large part from the Arthurian legends, which pitted brave Breton knights against evil enchanters. Reprising nearly abandoned distinctions that had been invented in the thirteenth to sixteenth centuries, fantasy long enjoyed pitting “black magic,” wielded by those who serve the forces of evil, against the “white magic” that is specific to heroes doing good.

Those symbolic constructions are frequently scrambled nowadays. Not only has Harry Potter done a great deal to redeem terms like witch, witchcraft, and wizardry, but most recent books attempt to explore magic’s social, political, or even economic and ecological implications. The Broken Earth series (N.K. Jemisin, 2015-2017), for example, describes a world in which some characters can control telluric power and tectonic plaques. When one of those magicians suddenly loses his mind, he causes a continent-wide natural disaster, plunging the world into a climate crisis that may bring about the end of civilization.

By the same token, more and more often, supernatural components are presented as a given, and are full-fledged narrative elements: the dragons that Lady Trent goes to study are part of an endangered species that is poached for its precious bones. The narrator has her hands full trying to protect them from human greed (Mary Brennan, The Memoirs of Lady Trent). Newt Scamander, the hero of the Fantastic Beasts films (David Yates, since 2016), set in Harry Potter’s world, has to fight a similar battle. The eponymous fantastic beasts, which are often inspired by our world’s mythological heritage, are being exploited for their powers or hounded, forcing the hero to protect them inside his magically expanding suitcase.

Both plots play out as transpositions of our real-world mass-extinction crisis and what part humanity is playing in it. By the same token, magic can empower authors to address complex themes. In the world of the Farseer Trilogy (Robin Hobb, 1995-1997), the Wit makes it possible to bond with animals, but its practitioners are looked down upon or even hounded and killed by crowds. The way they are treated is reminiscent of some contemporary forms of race- or religion-based forms of discrimination. Jagang, the hero’s opponent in The Sword of Truth (Terry Goodkind, 1994), sets off to conquer the world and “purify” it of magic by assassinating everyone who practices it. There too, one can easily spot echoes of very contemporary issues.