Heroes Forged by Their Quests

How do you give a character a heroic dimension? Set them on a quest that will force them to confront monstrous creatures. Older than fantasy itself, that plot still inspires the genre to this day.

Fantasy traditionally features heroes – or, more and more often nowadays, heroines. Often young, the main character usually starts out without the powers they will gradually acquire over the course of their adventure. One of the most common tropes is to make him or her the chosen one of an ancient prophesy, one who has been called by birth to defeat evil. Fantasy heroes, especially in the classic heroic-fantasy sub-genre, tend to have similar personalities: naïve, well-intentioned, naturally trusting, they are unlikely to try to take advantage of their authority for personal gain.

Authors nevertheless adopt extremely varied narrative strategies. There are stories of endearing anti-heroes, other authors prefer to concentrate on groups rather than individuals, still others relate tales in which the hero fails, joins the forces of evil – like Anakin Skywalker becoming Darth Vader, or simply decides to give up.

After all, the hero’s road is no primrose path! Their journey often takes the shape of a quest, one of the great narrative motifs even from well before fantasy. In any case, that is the basic premise of most of the world’s great stories, particularly myths. The hero sets off in search of a secret, like Gilgamesh looking for the one to immortality; a magical object, like Jason and the Golden Fleece; or a place, like Ulysses trying to get back to Ithaca, and Aeneas looking for a place to settle.

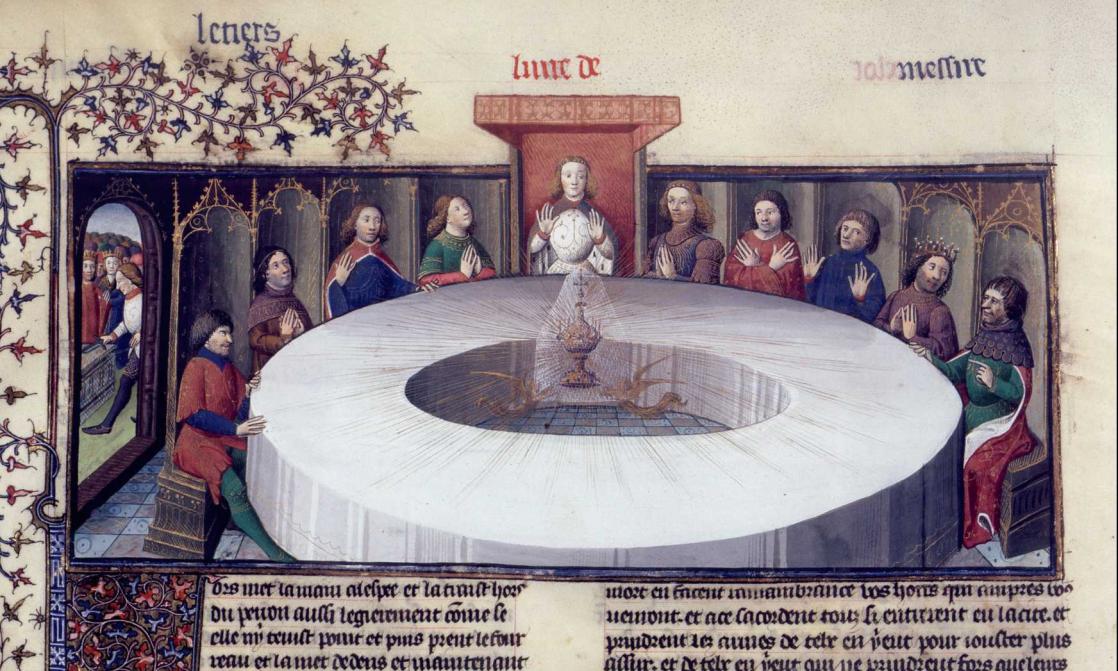

The Holy Grail: The Iconic Symbol of a Quest

In context, the Quest for the Holy Grail inevitably comes to mind. Although the motif does not appear in the earliest Arthurian texts – one must wait until Chrétien de Troyes’s Perceval to see it crop up – it soon goes on to occupy a critical role in both the medieval era and contemporary imagination. The iconic symbol of a never-ending quest, associated in everyone’s mind with concepts like knights errant, chivalry, heroic deeds, mysteries and magic, evocative of both the glory of Camelot and the “mists of Avalon,” without the shadow of a doubt, the Quest for the Holy Grail has had a profound influence on fantasy.

It should be remembered that a great many fairy tales also involve quests, making it a deeply familiar motif that we all integrated in early childhood.

Quests Hiding More Quests…

So it’s no surprise to see that quest took the lead as one of the most fundamental narrative structures in contemporary fantasy right from the start: L. Frank Baum (The Wizard of Oz), William Morris, J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis all used the theme in their novels. It can be seen in all media, as well. Many role-playing games, “You are the hero,” books, and adventure-type video games like the Zelda series provide examples of storylines composed around a fundamental quest – the hero usually has to gather fragments of a magical object that have been scattered around the world. Plenty of “subsidiary quests,” which may or may not be required, pop up around or within the main quest, enabling players both to explore the world in greater depth and to help their character make progress.

Although some works do attempt to avoid or to get around or beyond quests, the motif wields such powers of attraction that rare are the authors who never succumb to the temptation. While the first six volumes of Harry Potter, for example, avoid or only very partially address the idea, in the seventh and last volume, the hero must track down two sets of magical objects (the "deathly hallows" and the evil “Horcruxes”) that are needed for his ultimate victory. It must be acknowledged that the motif offers several critical narrative advantages. First and foremost, it is almost infinitely adaptable: the hero can be searching for a place, a magical object, a person, knowledge, a mythical creature, a text, etc. The quest may come in the guise of a police investigation, as in urban fantasy, or have a more unusual framework. Marie Brennan’s novels, for example, describe a female naturalist’s journeys of exploration as she carries out research on dragons around the world.

Adventure and Initiation

The quest is generally imposed on the hero or heroine, most often for an extremely urgent purpose – saving the world by finding or destroying a magical object – which establishes the character’s heroic nature right from the start. They haven’t chosen to embark on the long, perilous and trying journey of their own accord, but, considering the stakes, they simply can not shirk the duty that has been thrust upon them. In that context, the quest often takes on spiritual or religious significance, which is another legacy of medieval literature. In fantasy, and unlike the quest for the Grail, most quests end successfully, although a certain number of works prefer to avoid the predictable ending, either with an unexpected negative outcome (Le Tendre and Loisel’s La Quête de l'Oiseau du Temps (The Quest for the Time-Bird)), or by bringing the hero back to their starting point (Alain Damasio’s La Horde du Contrevent (The Into-the-Wind Horde)).

Bringing great subtlety to the idea of journey of initiation, several writers have portrayed heroes who choose to free the object they have been searching for once their quest has come to an end, because the journey has gradually led them to evolve. Harry Potter chooses not to possess the Elder Wand; at the end of Neil Gaiman’s Stardust, when Tristran Thorn finds the young woman he chased a shooting star for, he realizes that he is no longer in love with her. In stories like those, the quest itself matters more than achieving it, the journey more than the destination, and the search more than possession of the desired object.

However coveted they may be, the objects of quests are generally little more than pretexts. They are rarely actually used. Obtaining them matters more than possessing them, which makes them kin to filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock’s McGuffin principle. Quests can last days, years, or even centuries. They generally involve a journey, which enables authors to move their character or characters around their imaginary world, offering them an excellent excuse to explore it.

Monsters: Obstacles Like No Others

Quests are obviously always impeded by myriad obstacles. This creates plot twists and turns that extend the story without ever losing track of what’s at stake: the coveted object. One can see just how deep the influence of the quest for the Holy Grail is: setting off in search of Christ’s chalice, Arthur’s knights are constantly confronting new dangers, while being repeatedly set back on their path by a providential hermit. So the quest becomes an initiatory coming-of-age journey in which the hero or heroine matures over the course of the trials and dangers they must face.

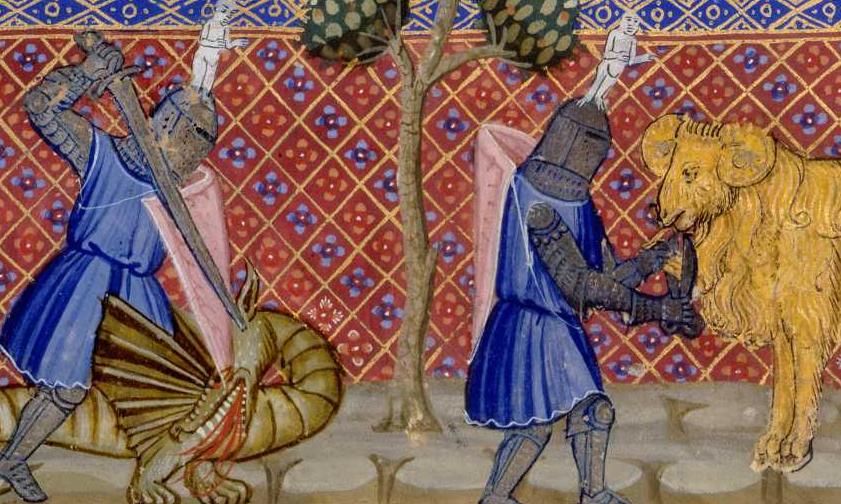

Monsters occupy a central place among those dangers, comprising the lion’s share of the pitfalls the protagonist encounters. Along his way, Bilbo has to outwit or overcome trolls, goblins, the strange Gollum, gigantic spiders, and, at long last, the dragon Smaug. The last adversary often comes in the guise of a monster, like the “final boss” in video and role-playing games.

Authors often draw on both European and other folklore and mythologies when creating fabulous creatures – centaurs, manticores, gorgons, minotaurs, etc. – although many of them also enjoy inventing novel monsters, from J.K. Rowling’s terrifying “Dementors” in the Harry Potter books to Patrick Rothfuss’s mysterious “Chandrians.”

In general, monsters are only there to act as flattering foils for the heroes, who prove their prowess by slaying them, or, occasionally, taming them. In this they are reenacting the legacy of countless medieval saints who slayed or tamed dragons. As with the heroic character or the quest motif, contemporary authors often reinterpret the figure of the monster: thus Stan Nicholls made a band of Orcs – among fantasy’s most iconic monsters ever since Tolkien’s time – the protagonists of his trilogy, while A Song of Ice and Fire features humans who are far more monstrous than the creatures they clash with.