From the Pre-Raphaelites to the Comics: Illustrating the Imaginative

Since the nineteenth century, great artist-illustrators from every generation have been portraying fantasy’s imaginative worlds. In a range of popular media, they have expressed their singularity by creating images of those worlds.

Fantasy is by nature a visual genre. Its very name calls on the imagination, and, therefore, on images. A large portion of the genre is meant for young readers, who are particularly fond of illustrations. And it’s no accident that throughout the genre’s history, some of its greatest authors have also been great artists.

The Origins: The Pre-Raphaelites and the Arts & Crafts Movement

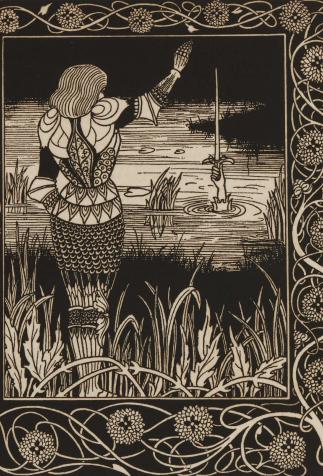

Victorian fantasy emerged within a larger aesthetic movement, one that showed tremendous interest in mythology and folklore, as well as a return to a certain image of the Middle Ages and the early Renaissance. The movement produced some remarkable achievements, particularly in terms of painting and architecture. The connection between the earliest works of fantasy and the artistic philosophy that was influential at the same time has been proven conclusively. The pre-Raphaelite movement not only forged the initial visual imagery of a certain type of fantasy – skewing it towards faerie, nature, and the Arthurian legend – it has also had the most long-lasting aesthetic influence on the genre as a whole.

In France, the painter Gustave Moreau (1826-1898) shared several favored themes and aesthetic stances with England’s pre-Raphaelites. He is seen as one of the precursors of the Symbolist movement that flourished in France and Belgium in the late nineteenth century in reaction to the era’s triumphant naturalism. That distinguished them from the realism that was one of the Victorian brotherhoods’ aims. It is also generally accepted that, with the engravings of Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898) and others, some of the roots of Art Nouveau’s modernism can be traced back to William Morris’s Arts & Crafts movement.

The Golden Age of Illustration

At the turn of the twentieth century, the “Golden Age of Illustration” refers to a period of prosperity for illustrators, particularly in England and America. The number of magazines and publishers was expanding rapidly. Between the advent of high-quality printing for a reasonable price and a rapidly expanded readership, major artists were willing to seek work in illustration, which was then a flourishing profession. Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) left a lasting impression on myths, legends and fairy tales for children, as did his fellow illustrators Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), Kay Nielsen (1886-1957), John Bauer (1882-1918) and Sidney Sime, who illustrated Lord Dunsany’s books.

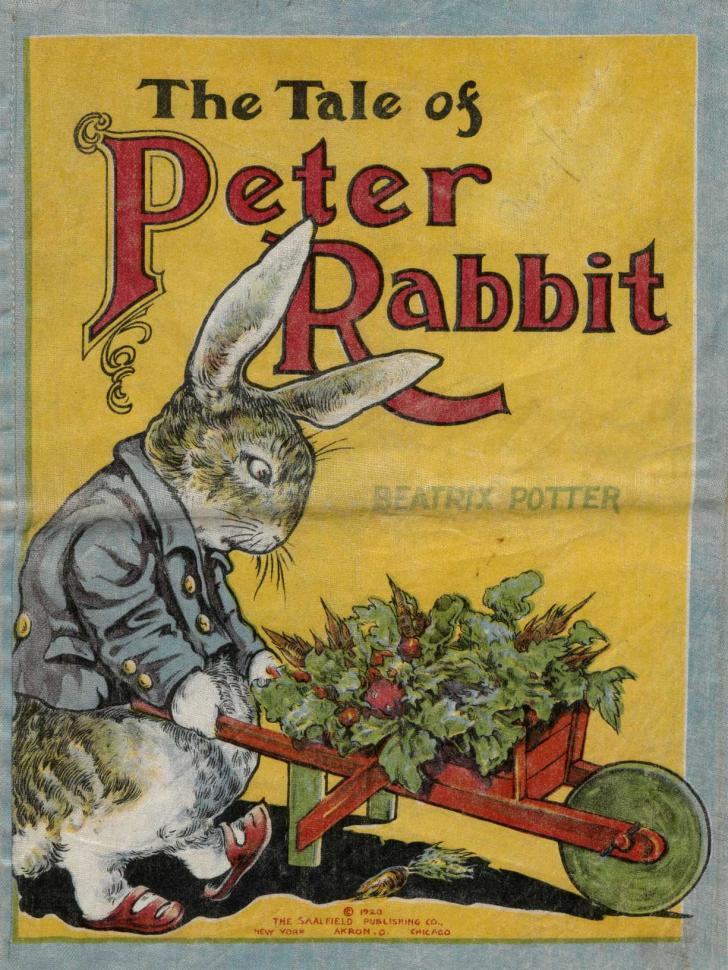

It was also a highly fertile time for illustrated children’s books, particularly animal fantasy, which features societies of anthropomorphized animals, as in the books of Beatrix Potter (1866-1943). Illustrations by Ernest Howard Shepard (1879-1976) enhanced both Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908) and the first volumes of A. A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh (1926).

Generations of Major Illustrators

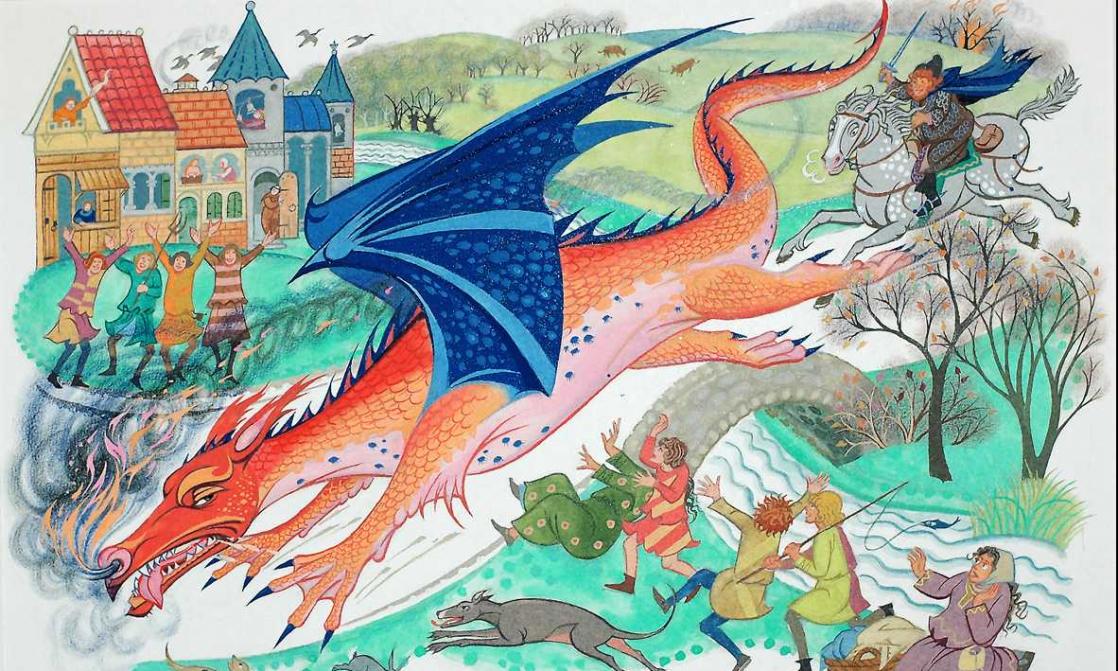

For over a century since that golden age, illustrators have been leaving their mark on the history of fantasy. Pauline Baynes (1922-2008), for instance, is remembered for having been personally chosen both by Tolkien to illustrate Farmer Giles of Ham (1949) and The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and by C.S. Lewis for The Chronicles of Narnia (1950-56). Her images have withstood the test of time, and are still associated with Lewis’s series.

Coming after William Morris and, to a lesser extent, Tolkien, who was also a talented amateur illustrator, Mervyn Peake (1911-1968) offers another example of an all-around artist. A professional illustrator known for his drawings for Alice in Wonderland, he is also responsible for a very unusual body of written work, the Gormenghast trilogy (1946-1959). The saga’s setting is the sprawling, decaying Castle Gormenghast, which is described in a highly visual style. The characters are odd creatures forged through allegiance to absurd ancient rites, at once profoundly human and reminiscent of charcoal sketches of grotesques.

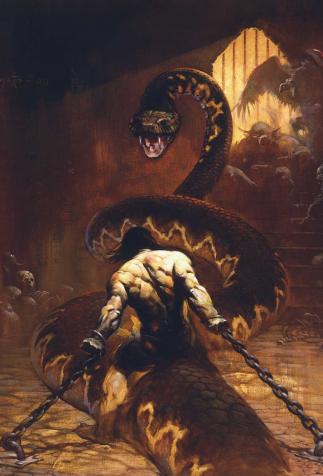

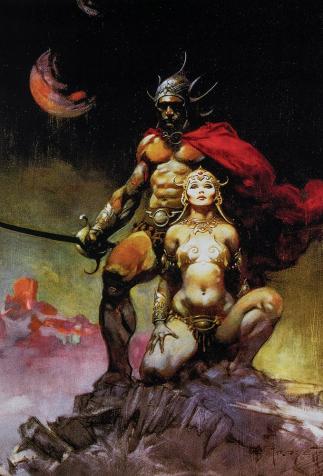

Frank Frazetta is undoubtedly the world’s best-known illustrator of fantasy. He is indissociable from the genre’s boom in America in the late 1960s and into the 1970s, period which corresponded to the summit of his career. He worked for various comic books in the early 1950s, but it was his covers for the Conan books, published from 1966, that made his darkly dynamic style famous. His work was truly seminal, establishing a visual style for American heroic fantasy. During that same period, he also illustrated new editions of E.R. Burroughs’s work (Tarzan and John Carter), among others.

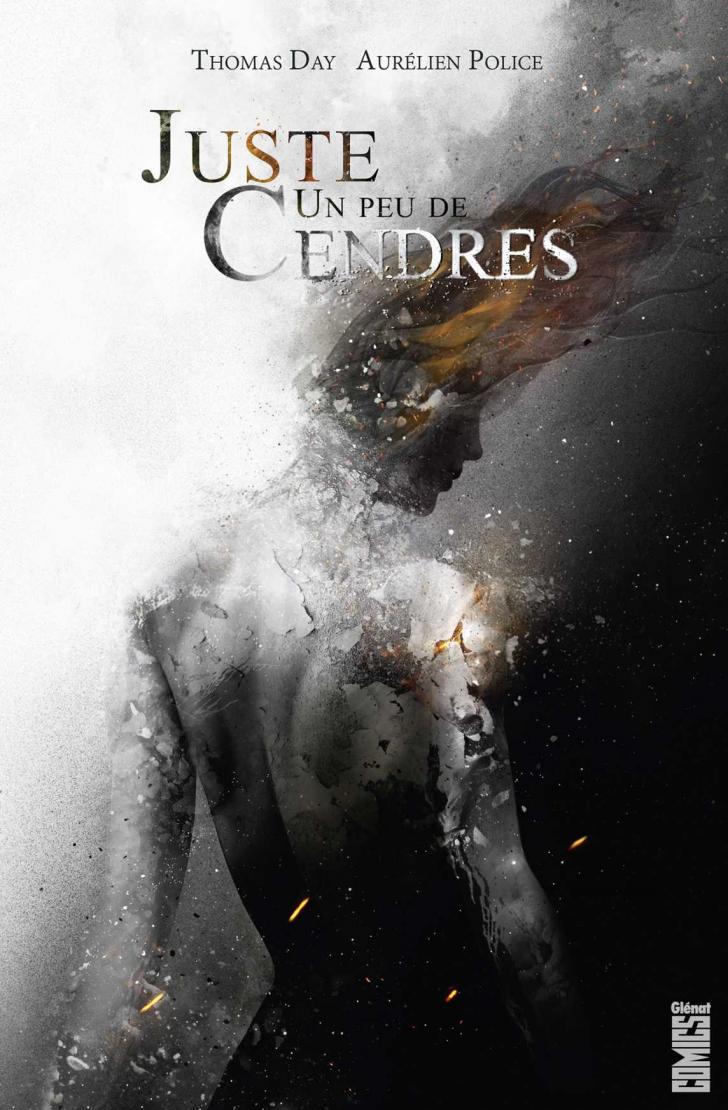

The husband-and-wife team of Brian and Wendy Froud are key artist from the next era. Their impact has been greater on how we visualize faerie’s marvelous little people: trolls, fairies and goblins. French illustrators like Didier Graffet, Nicolas Fructus and Aurélien Police have also chosen to specialize in fantasy, and have created a great many strikingly memorable book covers and posters.

Comics: A Favored Playground

Fantasy comics are a world unto themselves, with continents: Japanese manga, American comic books, and the larger, hard-cover “albums” that are typical of the Franco-Belgian school. Populated right from the start by neo-knights and neo-Vikings, there were founding characters in both the American and French traditions: Harold Foster’s Prince Valiant (from 1937), an Arthurian comic strip that was translated into French right away and published in the era’s illustrated magazines; and Thorgal, created in 1977 by Grzegorz Rosinski for Le Journal de Tintin. In both cases, a more or less “historical” setting featured what were very often magical tales. That backing and forthing between Medieval realism and fantasy has remained a constant throughout the history of this rich corpus.

In France, the sub-genre has remained fairly circumscribed, with only a few key examples. It started with Peyo’s Johan et Pirlouit, in the early 1950’s, in the weekly comic magazine Spirou; then, after Thorgal, Le Tendre and Loisel’s La Quête de l’Oiseau du temps (Quest for the Time Bird) since 1983, and Froideval and Ledroit’s Chroniques de la Lune Noire (Black Moon Chronicles) 1989-2008. Illustrators like Moebius, Topor and Druillet fall under science fiction rather than fantasy.

In the United States, the 1970s and 80s focused much more on heroic fantasy, but in any case, in the wake of the wildly popular Conan, a single editorial line steamrolled everything: Marvel comics. Adapted from Howard’s books in the 1970s, the best-selling Conan, Kull and Red Sonja inspired a wave of pale imitations. Wendy and Richard Pini’s Elfquest (from 1978) stood out from that pack, with its psychedelic aesthetic and its elaborate plot, conceived as a whole right from the start. Another magnificent maverick: Neil Gaiman’s Sandman (from 1989), a dark fantasy series about powerful god-like beings called the Endless (Destiny, Death, Desire, Despair… and above all, Dream, the lord and personification everything that is not in reality), provided much-needed renewal.

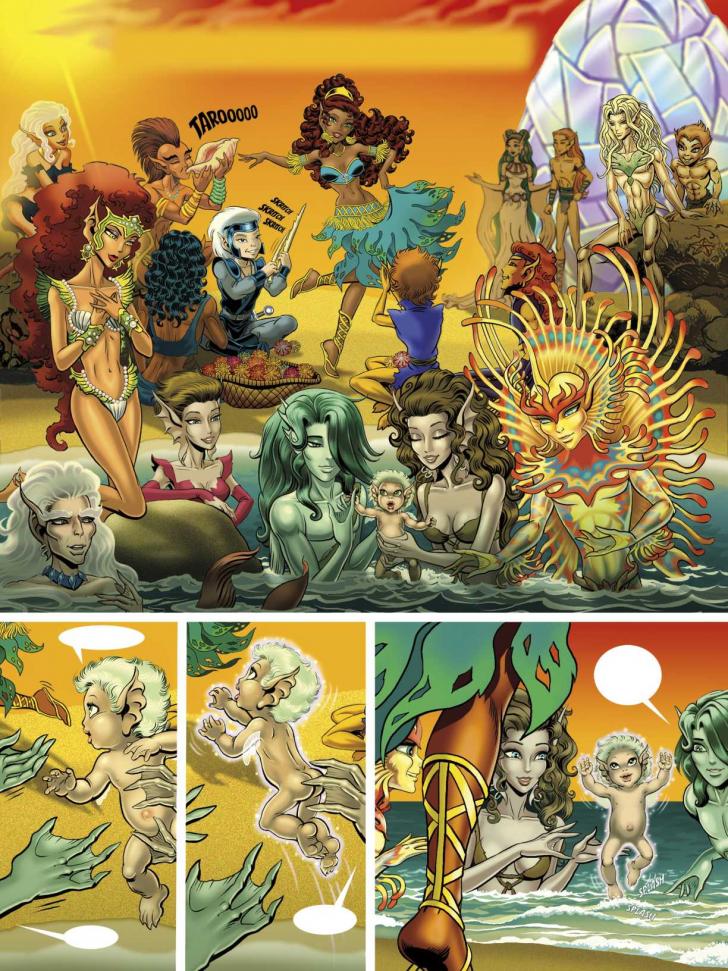

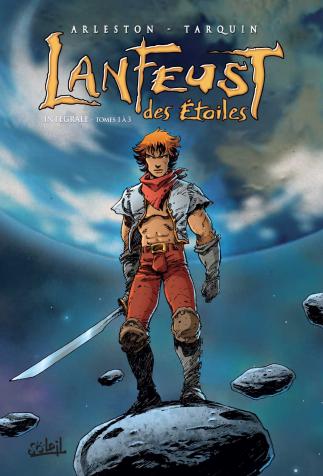

Adaptation is still a constant in fantasy comics, whether they provide visual interpretations of games or novels. But in the mid-1990s, the genre really took off, both in comics and in literature, becoming more diverse. In France, the success of Arleston and Tarquin’s Lanfeust of Troy got the ball rolling. First published in 1994, it has been followed by other series about the world of Troy, a cross between fantasy and science fiction.

Since that time, fantasy comics in the large, often hardcover format that is common in France, have established themselves as key to the market. Delcourt Editions, which already had an excellent collection called “Terre de légendes,” (Land of Legends), and which had published Chauvel and Lereculey’s Arthur: A Celtic Saga (from 1999), dove into the expanding children’s comics market, with, among other series, Patrick Sobral’s Légendaires (since 2004). Then in 2011, they bought Soleil, a publisher based in the south of France that had brought out Lanfeust. In 2002 they founded a collection called “Soleil Celtic,” run by Jean-Luc Istin, a very popular author in his own right.

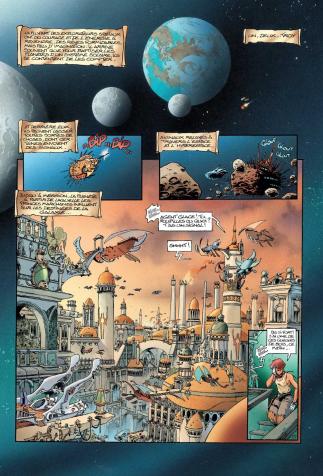

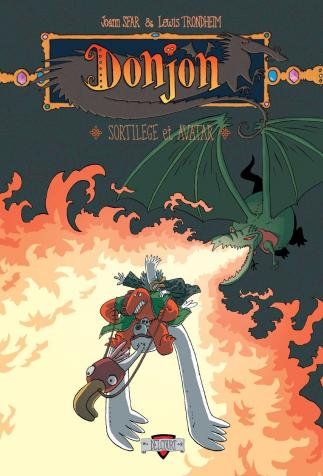

It was Delcourt, once again, that took a bet on one of the most surprising and ambitious adventures in French fantasy comics, the “hyper series” Dungeon, which has had several sub-series (since 1998). Written by Joann Sfar and Lewis Trondheim, two major and extremely productive figures on the French graphic-novel scene, different volumes have been illustrated by various artists. The first few stories have been published in English by NBM Publishing, originally in a black-and-white periodical format, and later as color graphic novels. Hundreds of volumes were planned, and 41 have been published so far. They were grouped into five series plus a “bonus” until a temporary conclusion in 2014. The series was re-launched in 2020 with two new volumes. This is another example – from the world of comics this time – of fantasy worlds’ all-embracing and intensely productive nature. This particular case is a parody of role-playing games, with their levels and their recurrent but ever-changing characters.